Gripping accounts of Irish famine by lone-walking American woman

I can still vividly recall many of the flickering black-and-white scenes from an old 16mm film which I watched, frightened and awestruck, in the early 1950s.

It was a drama-documentary and the highlight was journalist Henry Stanley finding the ‘long-lost’ Livingston near Lake Tanganyika in 1871 and uttering the famous phrase - “Dr Livingstone I presume?”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe doctor had been trekking into central Africa, searching for the Nile’s source and reporting on slavery, but he hadn’t been heard of for many months.

In my mind’s eye I can still see long lines of captive slaves, tethered together, and war-painted, native Africans attacking Stanley’s search-party, which they mistook for slave traders.

The action on the screen was unimaginably far away, distanced by uncountable years and miles, yet the thick jungle, the poisoned spears and the wild animals brought terror into my young imagination.

Little did I know that something similar had happened ‘down the road’ almost at the same time as Livingstone embarked on his first African adventures.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe ‘natives’ and wildlife were infinitely less aggressive and the vegetation wasn’t as dense but the heroism and compassion was just as evident.

From Scotland, 28-year-old Livingstone travelled to the edge of the Kalahari Desert in southern Africa in March 1841.

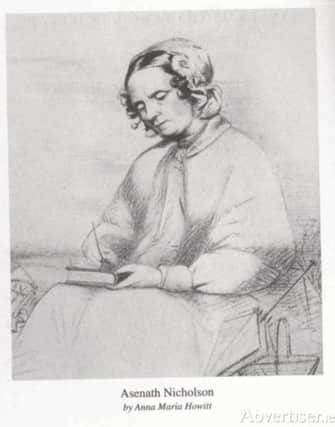

From Vermont, New England, 52-year-old Asenath Nicholson arrived in Ireland in May 1844.

Livingstone was in Africa to preach, heal, explore and abolish slavery.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMrs Nicholson was in Ireland with similar objectives, though the ‘enslavement’ here was to the mass starvation and relentless poverty of the Great Famine.

The Scottish doctor and the American landlady both kept meticulous records.

A News Letter reader’s recent e-mail to Roamer outlined Asenath Nicholson’s remarkable philanthropic pilgrimage to our tragic, hunger-torn island.

The e-mail referred to several of her books and diaries.

She visited Ireland twice, and her first account, ‘Ireland’s Welcome to the Stranger’, was originally published in 1847. ‘Annals of the Famine in Ireland’, published in 1851 about her second visit, has been edited by academic and author Maureen Murphy and reprinted by The Lilliput Press.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe heart-breaking news that travelled the world about the famine brought aid and cash to Ireland along with a wide variety of philanthropic visitors.

Asenath Nicholson, previously a boarding-house owner in New York, was different to most of the other visiting philanthropists being a woman, alone, and an enthusiastic campaigner back home for a vegetarian and caffeine-free diet.

She travelled extensively in Ireland, mostly walking whilst singing hymns loudly enough for all to hear as she trod the countryside.

She once stopped on a Galway lane to rest her aching feet and legs.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLeaning against a wall she remembered what her friends back home had told her when she announced her intention to help the Irish.

She was very thoroughly advised that her proposed trip was reckless and that she would undoubtedly damage her health.

The lonely woman at the lonely stone wall pondered - would she rather be in her New York kitchen?

“No,” she thought decisively “I would not.”

She noted later in her diary “Should I sleep the sleep of death, with my head pillowed against this wall, no matter. Let the passer-by inscribe my epitaph upon this stone. It shall only be a memento that one in a foreign land lived and pitied Ireland, and did what she could to seek out its condition.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBorn in Vermont in New England in 1792, Asenath Hatch was brought up in a strict, Protestant, Bible-reading family.

Her Christian name was taken from the Book of Genesis. Aged 16 she chose to become a teacher and around 1825 she married Norman Nicholson, a widower with three children.

They moved to New York and opened a boarding house in 1831.

The boarding house combined “comfortable rooms” with a strict observance of ‘no alcohol’, ‘no coffee’ and ‘no meat’!

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShe also worked with the Irish poor in the infamous Five Points district of New York where she declared the ‘huddled masses’ of Irish emigrants to be “a suffering people” and became determined to visit Ireland.

Her boarding house thrived and her marriage didn’t, ending probably around 1839.

Asenath spent more and more of her time with the burgeoning number of Irish emigrants arriving in New York, and in 1844 she set off for Ireland to learn more about them.

Her plan was to walk through the country, giving Bibles to the poor, and reading it to those who couldn’t read.

She believed that this would be a source of comfort.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor nearly two years she walked the length and breadth of the country, quickly grasping the urgency of a growing disaster - the Great Hunger.

“From the beginning her mission was difficult,” wrote one of her book reviewers, “Catholic people regarded Bible readers as proselytes, while the Protestant missionaries rejected Nicholson’s democratic ideas.”

She returned to America to write and campaign, and returned to famine-gripped Ireland in 1847 where the country was overshadowed by death, starvation, disease, and emigration.

This time she distributed food instead of bibles.

Nicholson’s written account of her first visit to Ireland published in 1847 was entitled Ireland’s Welcome to the Stranger; An Excursion through Ireland in 1844 and 1845 and her second visit was published in 1851 as Annals of the Famine in Ireland in 1847, 1848 and 1849.