Great Unionist Convention of 1892 showed Ulster's resolve to remain in UK

Going back 125 years, the United Kingdom was on the cusp of the general election of 1892.

The evidence of by-elections suggested that W E Gladstone, the Liberal leader, would return to 10 Downing Street with a healthy parliamentary majority.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs a second Home Rule bill took pride of place in Gladstone’s electoral platform, Ulster, Ireland and the whole UK was about to be plunged into a second political crisis.

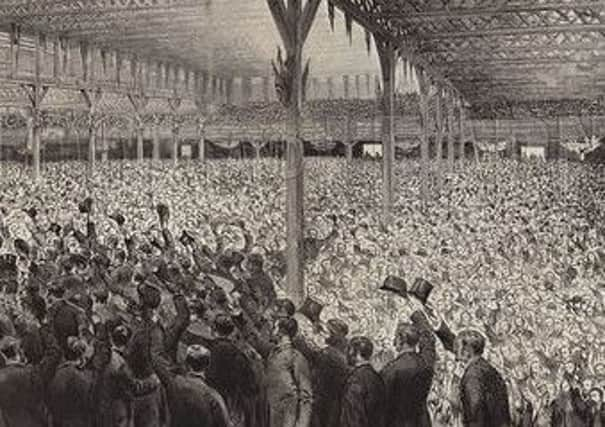

To demonstrate their whole-hearted opposition to Home Rule, Ulster unionists organised a Great Convention in Belfast with almost 12,000 democratically chosen delegates from every parliamentary constituency in Ulster.

The meeting began with prayer from the Anglican Archbishop of Armagh, a Scripture reading from a former Presbyterian moderator and the singing of a Psalm.

The convention successfully transcended the normal divisions of denomination, class and politics. Denominational differences were more pronounced then than today but Anglicans and Presbyterians buried their deep-seated differences in defence of the Union.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe importance of the Land Question in late 19th-century Ulster can scarcely be exaggerated but landlords and tenant farmers managed to sit side by side as did representatives of Ulster’s industrial and commercial elite and their employees.

Conservatives made common cause with Liberals, their former political rivals and opponents. The convention’s proceedings were carefully choreographed to underscore the unity of the unionist community.

Because no building in Belfast could accommodate 12,000 people, a convention pavilion was specially erected for the occasion.

According to the Belfast News Letter, day and night Belfast’s finest foremen and carpenters ‘worked in the spirit of their detestation of Home Rule’ to complete the task in less than four weeks.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe exterior of the pavilion was decorated with heraldic devices, emblazoned with apt slogans and bedecked with flags. Among the mottos prominently displayed was ‘Ein go Bragh’ (‘Ireland for ever’ in Gaelic).

Irish in the 1890s was comparatively free of political baggage. The Revd Dr R R Kane, a leading Belfast Conservative and the Orange county grand master of Belfast, was an Irish language enthusiast and delivered a speech (in English) at the convention.

The convention passed two resolutions, the first of which was a cogent and intelligent statement of the unionist case against Home Rule. The second resolution expressed sympathy and support for unionists in the other three provinces.

The idea of a convention as a response to the threat of Home Rule was first raised in May 1886 by James Henderson, the editor of the Belfast News Letter and chairman of the Ulster Loyal Anti-Repeal Union.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, the proposal was overtaken by events when Gladstone’s first Home Rule Bill was defeated in the Commons on June 8, 1886.

The idea of a convention was revived at a banquet in London to celebrate Joseph Chamberlain’s assumption of the leadership of the Liberal Unionists (ie those Liberals who repudiated Home Rule).

The convention is usually viewed as the brainchild of Thomas Sinclair, Ulster’s pre-eminent Liberal Unionist who in 1912 would be the wordsmith who drafted the Ulster Covenant.

How precisely the credit should be apportioned between Joseph Chamberlain and Thomas Sinclair is probably impossible to say.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJ L Garvin in his Life of Joseph Chamberlain does not claim credit for the subject of his immensely detailed biography.

On the other hand, J R Fisher in his history of the Ulster Liberal Unionist Association claimed that the idea of holding a convention ‘was conceived by members of the Ulster Liberal Unionist Association’. If so, one member in particular, Thomas Sinclair, deserves the credit. It was Sinclair who translated the idea into a practical proposition, organised it and made one of the best speeches.

Sinclair told the delegates to the Ulster Unionist Convention: “It is our conviction, founded on the prosperous experience of our own province, that the most intimate union with the enterprise and sympathy of wealthy Britain is essential to the well-being of our poor island.”

Sinclair denied that any of the delegates were making a ‘demand for Protestant ascendancy’ and repudiated John Morley’s assertion – a man whom he referred to as ‘Gladstone’s ablest lieutenant’ – that ‘Ulstermen’ wished ‘to trample upon what they look upon as an inferior race’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe added: “I speak as the representative of thousands of delegates to this convention, who, like myself, are Liberals born and bred, who have in their veins the blood of Scottish Covenanters and English Puritans, and the best part whose political lives has been spent resisting and pulling down ascendancy. Is it a likely thing that we, who as members of the Liberal party, worked heart and soul in alliance with our Roman Catholic countrymen for the redress of civil and religious inequalities, are about to demand their imposition?

“Our children – whether Roman Catholic or Protestant – are born into the enjoyment of electoral freedom, and of a religious equality, and an agricultural emancipation unknown in England and Scotland.

“I speak for every man of the 11,000 picked Ulstermen who compose it, and through them for the Protestant majority of the people of Ulster, when I declare that the desire either for Protestant ascendancy or to trample on the rights of the humblest nationalist in Ireland is non-existent in Ulster.”

The convention proved to be the launching pad for the best election for unionism in Ireland from 1885 until the more equitable distribution of seats in 1918. In all, 23 unionists were elected, four of them outside Ulster.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUnionists won 19 of the 33 constituencies in Ulster, a clear majority, reversing the humiliation of the election of 1885 and improving on the position achieved in the election of 1886.

The convention made a favourable impact on the mainland. The anticipated large independent Liberal majority failed to materialise and the Home Rule majority in the House of Commons was curtailed to 40.

The narrowness of the majority in the Commons was important in that it gave peers the confidence to reject the second Home Rule bill on September 8, 1893 in the sure and certain knowledge that the bill did not enjoy the whole-hearted support of the country at large.

Above all, the success of the convention was a tremendous boost to unionist morale in Ulster. The true significance of the convention was that it was an impressive demonstration of the resolve of Ulster unionists to remain citizens of the then United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

The convention demonstrated a spontaneous solidarity in defence of that Union. Furthermore the convention demonstrated that Ulster unionism was a popular, broadly-based and democratic movement.