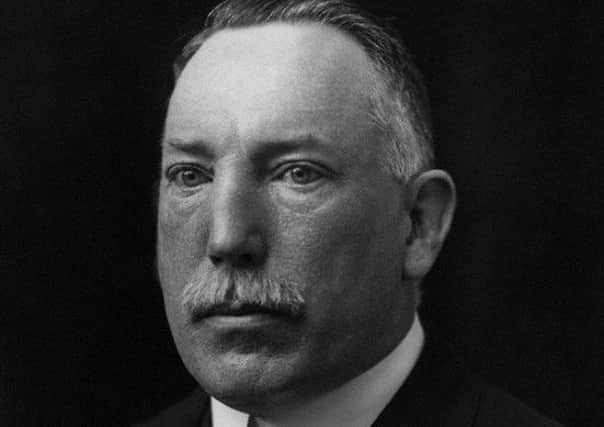

James Craig, implacable opponent of Home Rule who became NI’s first prime minister

James Craig, Northern Ireland’s first prime minister, spent almost half his political career opposing Home Rule and the remainder of his political life as the premier of a Home Rule administration.

As prime minister, Craig not only had to oversee the creation of the institutions of the state but he had to defend the nascent state against internal and external threat.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe years which witnessed the birth pangs of Northern Ireland were violent as the IRA sought to destroy the new state. Between June 21, 1920 and June 18, 1922 428 people were killed and a further 1,766 wounded. Over half of these occurred in 1922. In that year 232 people, including two Unionist MPs, were killed, nearly 1,000 wounded, and significant amounts of property destroyed.

The IRA also kidnapped a large number of prominent border unionists in February 1922 and seized part of Co Fermanagh – the so-called Pettigo triangle – in May 1922.

There were other threats to the survival of the state. As late as November 1921 Lloyd George was endeavouring to cajole and pressure Craig into agreeing to Ulster’s subordination to the Dublin parliament.

There was also the uncertainty created by the boundary commission. Craig successfully saw off all these challenges. In 1925 the Craig government signed a tripartite agreement with the governments in London and Dublin to preserve the Irish frontier as it was. The historian Bryan A Follis in ‘A State Under Siege’ (Oxford, 1995) has observed that “the successful birth of Northern Ireland was due to the iron will of the Ulster unionist government and the resolute leadership of Sir James Craig”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCraig also had to confront the problem of an ailing economy but devolution was ill-equipped to arrest the decline of the shipbuilding and linen industries, two of the three pillars of the local economy. Craig, however, could and did nationalise road transport, and introduce new systems of education and agricultural marketing.

He maintained party unity – a far more difficult task than is readily appreciated – and for 19 years he led the Unionist Party to large majorities in five successive general elections. However, the 1925 election, and in particular the success of four independent unionists and three labour candidates, gave him a shock. Contrary to popular opinion, the abolition of proportional representation in 1929 was directed against independent unionists and labour candidates rather than nationalists. In the general election of 1929 and 1938 he saw off the challenge of Temperance advocates and W J Stewart’s Progressive Unionists respectively. In 1938 a journalist told Craig – perfectly accurately – that he was ‘the one politician’ who could “win an election without ever leaving his fireplace”.

In April 1934 in a debate in the Northern Ireland House of Commons Craig famously said: “The hon. Member must remember that in the South they boasted of a Catholic State. They still boast of Southern Ireland being a Catholic State. All I boast of is that we are a Protestant Parliament and a Protestant State.”

This extract is frequently quoted to Craig’s disadvantage. The passage was immediately preceded by Craig asking Northern Ireland’s critics to “remember that in the South they boasted of a Catholic state”. Craig was specifically referring to Eamon de Valera’s assertion that Ireland was a ‘Catholic nation’. De Valera is rarely quoted to his disadvantage. In truth, the speech does not accurately represent Craig’s outlook because, following Carson’s injunction “to see that the Catholic minority have nothing to fear from the majority”, he endeavoured to conciliate the minority and establish good neighbourly relations with Dublin.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUnfortunately the Roman Catholic or nationalist community rarely responded to Craig’s overtures. Cardinal Logue refused an invitation to attend the state opening of the Northern Ireland Parliament in June 1921 and declined to appoint a chaplain to the Parliament.

Nationalist MPs did not take their seats in the Northern Ireland Parliament until 1925. Nationalists boycotted reviews of local government boundaries (the Leech Commission of 1922-3) and of education (the Lynn Committee of 1921-2).

Nationalist-controlled county councils refused to recognise the Northern Ireland Parliament.

Nationalist school teachers – encouraged by Michael Collins – refused to accept their salaries from the Ministry of Education in Belfast. Although one-third of the places in the new Royal Ulster Constabulary were reserved for the Roman Catholic community, Roman Catholics never took up their full entitlement.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJ J Lee, the former Professor of Modern History at Cork, readily acknowledged that Craig genuinely wanted good relations with the minority and the southern state but goes on to observe that “the reluctance of the Catholics in the North to recognise the legitimacy of his government, and the viciousness of both Protestant and Catholic extremists, soon convinced him that he must seek consolidation of his own forces rather than reconciliation with his enemies as his first priority”.

Throughout his life Craig exhibited a great capacity for friendship which could and did extend beyond the political divide to embrace Nationalist politicians such as Joe Devlin, the Nationalist leader, and Patrick O’Neill, the Nationalist MP for Mourne. Craig’s warm relationship with Joe Devlin was in marked contrast to the glacial relations which existed between W T Cosgrave, the Cumann na Gaedheal leader, and Eamon de Valera, the Fianna Fail leader, in the south.

At the outset of the Second World War, Craig said: “We are the King’s men, and we shall be with you to the end.” However, Craig did not live to see the end of the war.

He died on November 24, 1940 and was buried in the grounds of Parliament Buildings at Stormont.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough Craig was an important and implacable opponent of Home Rule and spent almost half his political life opposing it, he went on to spend the second half of his political career as a very effective prime minister in a Home Rule administration.

Nevertheless, there was a strong underlying consistency to his career in that he personified the iron determination of Ulster Unionists to remain British.