UVF gun-runner inspired devotion of Catholic troops he led into battle

On the eve of the 1641 rebellion, they owned properties in both the cities of Londonderry and Armagh, as well as lands in those counties and in Tyrone. Although the family is most closely associated with Springhill, the Moneymore property was a comparatively late acquisition.

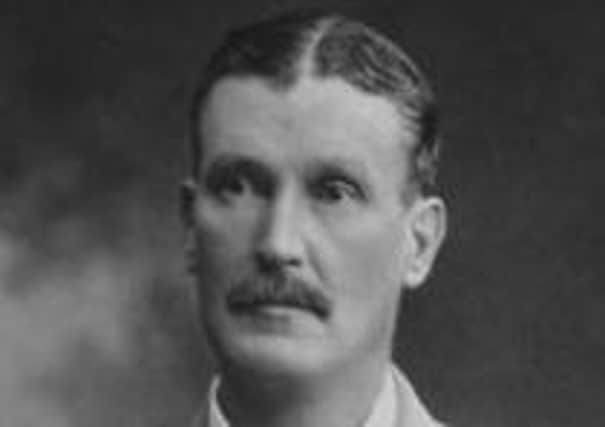

Born on November 23 1861, Jack Lenox-Conyngham was the third son of Sir William Lenox-Conyngham of Springhill. Jack entered the army in January 1881, obtained his commission six months later, and was promoted to the rank of captain in December 1889. He attained field rank in July 1900, and was appointed second-in-command of his battalion – the 2nd Connaught Rangers – in February 1906. He retired on half-pay in January 1912. At the outbreak of the Great War, he promptly volunteered for service and was gazetted commanding officer of the 6th Service Battalion of his old regiment.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis battalion, which he trained from its formation, was largely composed of men from the Belfast Regiment of the National Volunteers. A further hundred members of the battalion were drawn from the Fermanagh Regiment of the National Volunteers. Despite the fact that Lenox-Conyngham had been prominent in the UVF and the Larne gun running, he proved to be exceedingly popular with the troops he commanded.

Twice, at Fermoy in the early part of 1915 and at Blackdown (in West Sussex) later in the same year, Lenox-Conyngham personally received and welcomed Joe Devlin, the Nationalist MP for West Belfast and the man to whom the vast majority of the men of the 6th Battalion of the Connaught Rangers looked for political leadership, to visit his political followers and, in many cases, his constituents.

On December 18 1915 the 6th Connaught Rangers arrived in France, disembarking at Le Havre. The battalion served in France and Flanders all through 1916, 1917 and into early 1918. They took part in the Battles of Guillemont and Ginchy on the Somme (September 1916), the Battle of Messines (June 1917) and the Third Battle of Ypres (August 1917) but Jack Lenox-Conyngham did not live to participate in all these engagements because he was killed in action at Guillemont on September 3 1916, having gone over the top with his men to encourage them and to share their dangers.

Even before the 6th Connaught Rangers attacked just before midday, they had sustained nearly 200 casualties from shellfire.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdStephen Gwynn, the Nationalist MP for Galway, recorded: ‘On the day when the word to advance was given, our Battalion of the Connaught Rangers was where they had earned the right to be, in the foremost line; and the man who gave the word was the man who had made them what they were – worthy inheritors of a famous name. First out of the trench and waving them on, Colonel John Lenox-Conyngham saw them launched and he saw no more; a bullet took him in the forehead. I do not know what finer thing could have been desired for him. His work was accomplished. The battalion he had trained led the rush which swept through Guillemont that day, capturing the redoubtable stronghold of quarries.’

Of Lenox-Conyngham, Stephen Gwynn was proud to say: ‘I had the honour to know how he was worshipped by a thousand or so Irishmen – Catholics almost to a man’. In an article in the Daily Mail, entitled ‘A Colonel of the Irish Brigade’, Gwynn was even more expansive: ‘Never in my life was I so much in awe of any man; I never valued praise so much from any, and was never so resentful under reproof’.

He went on to observe: ‘There was another side of him that came out, though sparingly, amid the comradeship of our mess – a rare quality of charm. I found it myself in his occasional talk of men and things – above all of Ireland. I have known no better Irishman than this son of an Ulster house, whose kindred was deep in the Ulster Covenant.’

Lenox-Conyngham is buried at Carnoy Military Cemetery in France. The place is marked by the usual white Portland headstone but originally two wooden crosses were placed above the grave. Today these are on display in St Patrick’s Church of Ireland Cathedral in Armagh. Above them are the words: ‘O Death where is thy sting?’ and beside them is a framed copy of Philip Gibbs’ account of the attack of the 16th (Irish) Division at Guillemont.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGibbs wrote: ‘The charge of the Irish troops through Guillemont was one of the astonishing feats of the war. They stormed the first, second and third German lines, sweeping all resistance away. They were men uplifted out of themselves – ‘Fey’ – as the Scots would call it.

‘The whole attack from first to last was a model of efficiency and courage – all qualities that go into the making of victory were there … making a terrific weapon driven by high spirit. The artillery was in perfect unison with the infantry, the most difficult thing in war. It is impossible to overpraise the men, who were wonderful in courage and discipline.

‘So Guillemont was taken and held, not only by great gun fire but by men inspired by some spirit beyond ordinary courage. And one day these troops will carry the name on their colours, so the world may remember.’

Sadly, on the whole the world has not remembered. After the establishment of the Irish Free State, the Connaught Rangers was one of five Irish regiments that were disbanded. On June 12 1922 their colours, along with those of the other four disbanded Irish regiments, were laid up in a ceremony in St George’s Hall in Windsor Castle in the presence of King George V. There they occupy a place of honour to this day.