Drawings and paintings vividly depict terrors faced by ordinary people in the Great War

He has already had several showings of his drawings and paintings, mostly of soldiers and front-line stretcher bearers. Some of his canvases are studded with mud, leaves and poppy seeds collected from the former trenches and front lines which Leslie visited on regular trips to First World War battlefields and war-torn landscapes.

Along with fellow artist Colin Corkey, Leslie’s work is part of a two-man exhibition that opened last week in North Down Museum’s Long Gallery, in Bangor.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSunday’s centenary commemorations of the Armistice with its numerous memorial events here and around the UK were a profoundly moving and unforgettable tribute to those who fought and died in The Great War, the Second World War and in other more recent conflicts.

Colin and Leslie’s exhibition runs till January 27, 2019, and along with other ongoing memorial events, it echoes Sunday’s almost overwhelming personal, national and international act of remembrance.

And while it’s visually captivating, it’s very understandably not a comforting collection of canvases and installations – particularly with its unnerving title, ‘God Is On Leave’!

But even the most devout believers who experienced the unimaginable horrors of The Great War wondered if the Almighty had perhaps turned a temporary blind eye to mankind’s obsession with destruction and human annihilation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLeslie put a lot of groundwork and research into his paintings, reading letters from the front lines, diary entries, autobiographies and visiting museums across Europe.

The project left him with “an unshakeable wonder at the soldiers’ modesty and reticence at not being seen as heroes but as people doing what was expected of them,” he explained, adding:“They were brave beyond words.”

And like his own grandfather, they came home from the front lines “tortured with nightmares for the rest of their lives”.

He wants the exhibition to “show some sort of respect for a generation that can’t speak for themselves”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLeslie’s paintings, and Colin Corkey’s ‘Triptych’ (a three-panel installation) fit poignantly together in North Down Museum, and there’s a moving narrative behind both artists’ work.

After his mother-in-law was diagnosed with severe dementia several years ago, Leslie and his wife Elaine began the difficult and disheartening task of sorting through and clearing her house.

Elaine’s grandfather - Able Seaman Nicholas Crawford – served with the Royal Navy during the First World War when he saw action at Jutland, and amongst the books and documents they found in the house were some of his old pay books, discharge papers and medals.

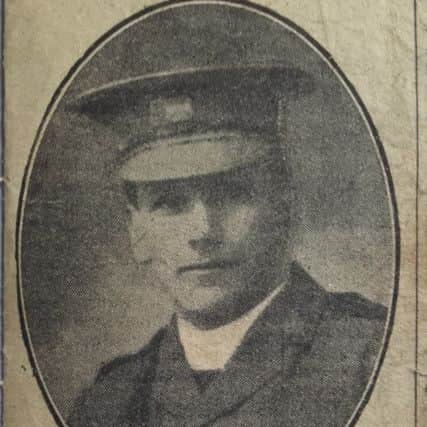

Amongst some First World War casualty lists from local newspapers they found a cutting bearing a photo of a padre, Reverend D S Corkey BA, captioned “wounded in France”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLeslie was certain that he recognised the face, confirmed when he showed the cutting to colleague-artist Colin Corkey.

It was Colin’s great uncle David and until Leslie showed him the cutting “the family had never seen a photograph of him in uniform”.

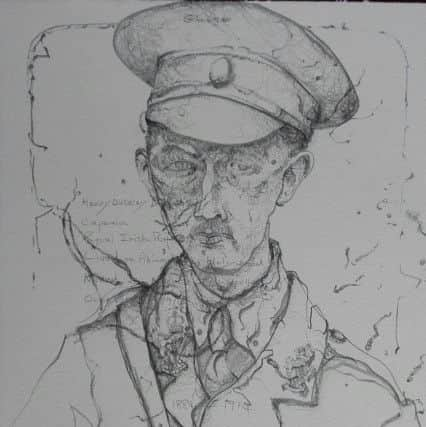

Colin painted a triptych of his great uncle David from the photograph, which hangs at one end of the Long Gallery, looking out over Leslie’s drawings of soldiers, some in glass cases and others on the gallery’s other three walls.

“Reverend D S Corkey lost his left arm on the front lines while giving Absolution to a dying man,” Leslie told me, adding: “And he insisted on going back to his duties with only one arm.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDrawings of soldiers, all from the Bangor area, “are laid flat in glass cases as if it is a communal, mass grave,” Leslie explained: “And around the walls are a group of paintings of young soldiers from various combatant nations including a Sikh cavalryman, paying respects to their fellow countrymen.”

In the introduction to a slim booklet about his tryptych – a Tribute to Rev David Corkey – Colin describes his great uncle as “…an avid reader, thorough in theological matters, a man of relentless energy which he expended on improving the plight of impoverished and vulnerable people and one who showed formidable courage at the expense of his own wellbeing and safety”.

The tryptych’s central panel is based on the photograph that Leslie and Elaine found, which, along with the two side-panels, depicts the life, faith, learning, dedication and remarkable courage of an army padre.

Colin’s three-panelled painting of the Reverend D S Corkey dominates one wall of the gallery, as if offering spiritual and physical aid to Leslie’s harrowing drawings and paintings of soldiers and stretcher bearers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLeslie has produced 250 drawings during the past two years – “the equivalent of an infantry company”, he told me.

The soldiers’ drawings in the glass cabinets are “young men from Bangor, Holywood, Donaghadee”, Leslie explained, “all known locally…young men with a thousand-yard stare. They’re looking at you, but they’re looking through you.”

And disturbingly, it’s a look that Leslie sometimes recognises in today’s generation.

There were young female nurses, padres, Red Cross medics, chaplains, soldiers and members of the Salvation Army – all together in the hideous surroundings of the trenches and front lines and they were all were ordinary human beings.

The shared humanity of the people so vividly depicted on the gallery walls and in the glass cabinets rises above the horrors of war.

Exhibition details are at http://northdownmuseum.com