First news of Armistice heard by wireless operator tuned in to the Eiffel Tower

“Sleep in peace my soldier laddie,

“Sleep in peace, now the battle’s over.”

In 1961, singer Andy Stewart put those moving words to a traditional piping tune, The Battle’s O’er, originally composed as a Retreat March in the late 1800s by Pipe Major William Robb of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders.

A retreat march was played to beckon soldiers back to their company after action for a roll call.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdVery appropriately, 1,000 pipers will play The Battle’s O’er throughout the United Kingdom and around the world at 6 am on 11th November marking the centenary of the ending of the First World War.

Countless towns, cities and communities across the UK are already planning all sorts of events and commemorations, from the most northerly inhabited Scottish island to the most southern, western and eastern towns in England and Wales.

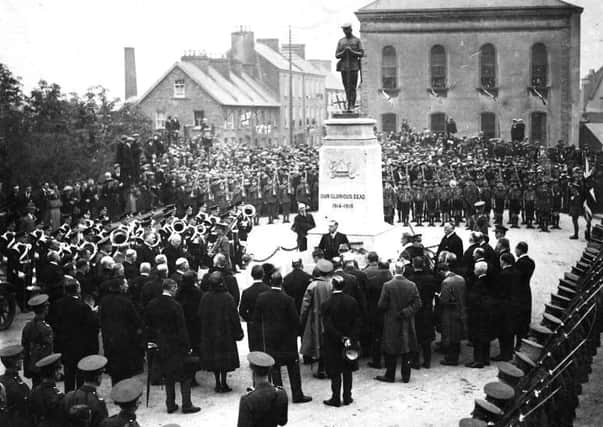

Whilst the most westerly commemorations in the whole of the UK will be held in Enniskillen, the Island’s townsfolk were the first to collectively celebrate the end of the First World War a century ago.

The historic scoop came because a wireless operator in the town’s military barracks inadvertently picked up a faint signal from General Foch, sent from an aerial on the Eiffel Tower.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

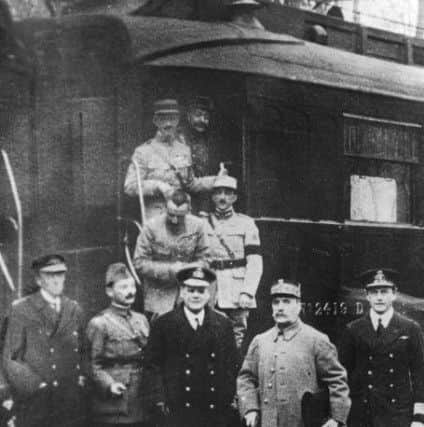

Hide AdFoch’s final Allied strategy brought victory in Western Europe’s land-war in 1918 and he was one of military chiefs who signed the Armistice in a railway carriage in the remote Forest of Compiègne, about 37 miles north of Paris.

Under the triumphant headline ‘Enniskillen First of All!’ the local Impartial Reporter newspaper boasted “the glad news of the signing of the armistice was known three hours earlier in Enniskillen than Belfast, Derry, Dublin or even in London itself”.

Prime Minister Lloyd George issued his historic announcement at 10.30 on 11th November 1918 – “The Armistice was signed at 5am this morning and hostilities are to cease on all fronts at 11am today.”

“Enniskillen on the other hand was acquainted with the official text of Foch’s historic message as early as 6.45 am,” the Fermanagh Times newspaper reported, adding “and shortly after seven o’clock the bells of the Parish Church were peeling forth the song of victory.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOperators in charge of the wireless station in Enniskillen’s military garrison “had been on the ‘qui vire’ (high alert) practically all night in the hope of some definite information coming through” the Fermanagh Times explained “and at around half past six am a faint message was caught by their instrument and taken down which read as follows: ‘Hostilities will cease on the whole front from November 11, at 11 o’clock (French time). The Allied troops will not, until further orders, go beyond the line reached on that day and at that hour. Signed Marshall Foch.’”

The happy news from the Eiffel Tower spread instantly around the barracks, greeted by deafening cheers from the soldiers who quickly emptied into Enniskillen’s slumbering streets.

The Fermanagh Times reported “the townspeople knew at once that something of importance had occurred”.

Not content with merely shouting about the Armistice, the soldiers from the barracks announced the news using every decibel that they could muster.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Townspeople and people for miles around,” recounted the Impartial Reporter “learned of the good news of the termination of the war by the firing of guns, the sounds of trench mortars and machine guns and the discharge of rockets from the military barracks. The salvos of guns were accompanied by the hooting of the factory sirens, and the church bells rang out and before breakfast the whole town was beflagged.”

A correspondent from the Belfast Telegraph, who happened to be in Fermanagh, wrote: “I was spending the weekend in the mountains in the far north-west, about 20 miles from Enniskillen, and as far again from anywhere else. I was getting ready for the road early on Monday, and was out having a wash at the water barrel when I suddenly observed skyrockets being sent up from Enniskillen, which proclaimed to the country for miles around that peace had been declared. Shots were fired and cheer answered cheer from the hilltops in far Fermanagh, where almost every house is represented at the front, proclaiming the glad tidings. Little villages and towns got busy very quickly getting out flags. When I reached Enniskillen it was decorated from end to end. The soldiers were parading the town.”

Amongst the numerous Remembrance Day Services and commemorative community events across Northern Ireland this November, there’ll be a special early morning memorial at Enniskillen Castle at 5.45am hosted by the Inniskillings Museum, before a piper joins with 1,000 other pipers around the UK and the world to play The Battle’s O’er at 6am.

All of Northern Ireland’s commemorative events will be announced in the media nearer the time, but back in 1918 a journalist with the Impartial Reporter noted a poignant detail when peace was announced in Enniskillen before dawn broke – “Amidst all the rejoicing of Monday morning, I heard one old lady remark to another ‘It is great rejoicing for some, but not for me.’ She had a son at the front from 1914, and had that day received word that he had been killed. Serving all those years and to be killed in the hour of final victory! It was indeed a case of sorrow, the harder to bear because of the general rejoicings.”