Scotland's and Ulster's historic links are explored today in Good Relations Week

Most of us know something about the historic links between Scotland and Ulster – this is a chance to understand more!

At its two nearest points along the coast, only 12 miles separate Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

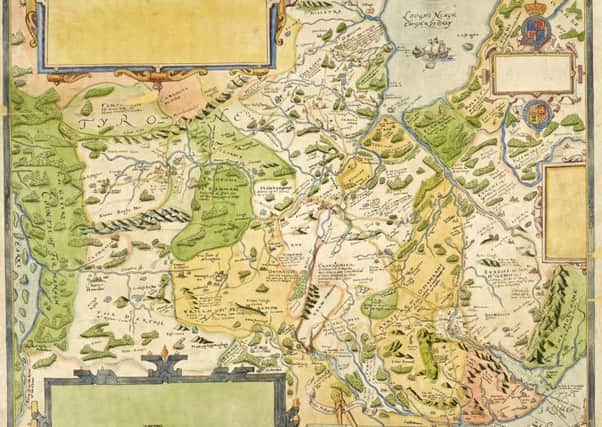

Hide AdYet, despite the expanse of the North Channel strait that lies between the north-east of Ulster and south-west of Scotland, both have shared close social, cultural and geographical connections for centuries.

The two have exchanged cultures, ideas and their native people and in many ways the North Channel has served as a link rather than a barrier.

Today’s Rathcoole Library event is a presentation by Matthew Warwick, Education Officer with the Ulster-Scots Community Network.

He’ll be exploring the legacy of the 17th century Scottish settlement in Ulster.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLong before the Hamilton-Montgomery Ulster-Scots Settlement of 1606, cited by historians and academics as one of the most important events in the history of the modern Ulster-Scots people, immigration and emigration between Scotland and Ulster was common.

In 1606, the two Ayrshire landowners – Sir James Hamilton and Sir Hugh Montgomery – entered into a land agreement with Con O’Neill, Earl of Clandeboye, which saw thousands of lowland Scots entering north Down and the Ards Peninsula.

Con O’Neill had been imprisoned at Carrickfergus Castle for levying war against Queen Elizabeth I of England. Fortunately for O’Neill, who was facing execution, the queen died, and King James VI of Scotland was next in line to the throne.

He would become King James I of England in 1603.

Seeing an opportunity to free her captured husband, O’Neill’s wife agreed half of the O’Neill estate to Montgomery in exchange for getting Con out of Carrickfergus Castle and procuring him a royal pardon.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA plan was hatched, and, with the help of the Montgomery’s in Scotland, O’Neill was transported across the North Channel to Scotland after a daring jail break.

However, Hamilton had heard of the deal to split the O’Neill estate in two.

Through a close associate of his, also an advisor to the King, he argued that the lands were much too expansive to be divided among the two and suggested a three-way split.

The king obliged.

It is widely accepted this single event – a privatised plantation – was the catalyst for mass emigration from Scotland to Ulster and a precursor to the official Plantation of Ulster, proclaimed by King James I in 1609 and commencing the following year.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHamilton and Montgomery unlocked a trading route between the Scottish village of Portpatrick and Donaghadee.

Attracting Scots and their extended families to Ulster with enticingly low rent, the first influx of Scottish settlers docked in the harbour of the North Down village in May 1606.

The floodgates had opened and Scots families began emigrating en masse to Ulster and a new life.

With them came language, culture and, among a myriad of other things – innovations – new building techniques, farming and agricultural practices, music, sport and more.

They transformed the geography of Ulster.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey urbanised and developed towns and settlements, including those in the North Down area such as Bangor, Holywood and Newtownards.

With such vast numbers of settlers arriving on the shores of Ulster to a predominantly rural landscape, there was an urgent need to engineer and construct more urban towns, villages and settlements – many of which have flourished and grown to become the modern hometowns we inhabit today.

Scholars have suggested that it was by the mid-seventeenth century that Ulster-Scot became its own identity.

It is this point in history that the first generation of Scots born in Ulster were approaching adulthood and presenting visibly different behaviours and practices compared with what the mainland Scots settlers had left behind in the early 1600s.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIndeed, during the 1640 General Assembly meeting in Aberdeen, attended by Ulster-based Presbyterian ministers, distinctly ‘Irish innovations’ were remarked upon, a clear sign that the attitudes and cultural practices of Ulster-Scots were becoming more and more dissimilar from the mainland Scottish.

Beginning with this generation the distinct language of Ulster-Scots started to come to the fore.

As a language it is a regional variation of Scots.

As English became the language of commerce and government, Ulster-Scots, alongside Irish, became marginalised and largely restricted to the countryside and the home.

Ulster-Scots has remained a vibrant spoken language in rural Ulster, particularly in counties Antrim, Down, Londonderry and Donegal.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is distinctive in many aspects of pronunciation, vocabulary and grammar.

Under the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages, approved in 1992 and signed by UK and ROI governments, Ulster-Scots became an officially recognised regional language of Europe.

Reflecting on the history of Ulster-Scots and looking ahead to the future of the people and language, it is interesting that as discussions about the possibility of constructing a bridge linking Northern Ireland and Scotland, the two historically-bound regions could enter an era where they are more connected than ever before.

Today’s Ulster-Scots History and Language Good Relations Week event, organised in partnership with Libraries NI and the Ulster-Scots Community Network, runs from 10am to 12 noon in Rathcoole Library in Newtownabbey.

The full Good Relations Week programme across Northern Ireland is at goodrelationsweek.com and you can keep up to date with it on Facebook and Twitter or join the online conversation using #GRWeek18.