Belfast Blitz: Attacks united city and led to hopes of less sectarianism, says historian

In his book Post 381, Jimmy Doherty, former air raid warden, describes the Belfast Blitz as being the ‘most disastrous event in the history of the city.’

Undoubtedly it was a traumatic and defining one, unprecedented in the history of Ireland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMajor cities in Britain experienced many more air raids than Belfast – Liverpool had 74 and Glasgow 11, whilst Belfast had just four.

But two of these were particularly severe. On Easter Tuesday night, April 15/16 1941, the bombs fell mainly on densely populated working class terraces in north Belfast, killing 740 civilians.

John Blake states in his official history of the war: ‘No other city in the United Kingdom, save London, had lost so many… in one night’s raid.’ On Sunday night, May 4/5 1941, the city’s industrial heart in the dock area was struck, and also east Belfast and the city centre, and over 190 citizens were killed.

Thus, overall, Belfast ranks 12th in a table of the urban areas in the United Kingdom that were subjected to German bombing, calculated by the weight of bombs dropped.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs a consequence of the 1941 blitz on Northern Ireland, over 960 civilians died, or were ‘missing presumed dead’.

In Belfast the bombs fell indiscriminately on Catholic and Protestant areas (the Parish Chronicle for St Patrick’s Catholic Church, Donegall Street, states that roughly 130 of its parishioners were killed on the night of April 15/16).

But military casualties must be added to these figures. There were 17,000 troops based in the Belfast area at the time, and others were home on leave.

On Easter Tuesday night Victoria Barracks was severely bombed, and at Newtownards airport 13 soldiers were killed when Nissan huts were struck. During the May 4/5 attack 13 soldiers died when the Military Hospital at Campbell College was hit.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAmongst other incidents, two gun emplacements were blown up during the raids, causing casualties. Thus, the total number of blitz fatalities is over 1,000.

In addition, over half of the city’s housing stock was destroyed or damaged (56,000 houses), and half of its public elementary schools. Roughly 50,000 people were left homeless. The impact on civilian morale was dramatic; officials estimated that by late May 1941, 220,000 had evacuated from Belfast (about half of the city’s population); such was the atmosphere of panic and fear.

The blitz made a deep impact on the lives of its citizens – on families and communities, and on the cultural, educational, social, economic, and political life of the city and of Northern Ireland. Some have suggested that it had positive influences – for example, that it alerted politicians and citizens to the scale of poverty in Belfast, and generated a will to try to eradicate it.

Those who lived through it often claim that it also helped ease inter-communal tensions. In the context of total war, partition became a less dominant political issue.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDuring the air raids, both communities experienced the loss of family and friends, evacuated and ‘ditched’ in fear and panic in their aftermath, served together in the civil defence services. There are also well-known examples of both Catholics and Protestants sheltering together as the bombs fell – in the vaults of Clonard monastery, in the basement of May Street Presbyterian Church, in the boiler-room of St Ninian’s Church of Ireland church, Greencastle.

At the time some hoped that the blitz would lead to improved relations between northern and southern Ireland.

Certainly much sympathy was felt in Eire for the sufferings of the citizens of Belfast. After the blitz Dr Eduard Hempel, the German minister in Dublin, complained of the rank hostility being shown to him – of people shaking their fists at him, of receiving abusive telephone calls, and hate mail.

One of the letters sent to him, read: ‘may the blood of the tiny children in Belfast call forth the vengeance of God on your own innocents. Better that they die now than live to realise the stain of their own fathers. To Hell with Hitler!’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEire provided fire assistance after both Belfast’s major raids, and catered for the northern evacuees who fled South. Some historians have concluded that the Luftwaffe’s bombing of Dublin (May 30/31 1941) was an act of retaliation by Germany for Ireland’s cumulative breaches of neutrality, with the aid it gave to Belfast after the blitz being regarded as the ‘last straw.’ Undoubtedly, the Belfast blitz helped strengthen Stormont’s relationship with Westminster. In Churchill’s phrase (in 1943) the ‘bonds of affection between Great Britain and the people of Northern Ireland have been tempered by fire and are now, I believe, unbreakable.’

After the war, he wrote: ‘a strong and loyal Ulster will always be vital to the security and well-being of our whole Empire and Commonwealth.’

During the conflict Northern Ireland had provided vital naval and air bases and ports, served as a military training ground, and supplied food and munitions for the national war effort. After it, British politicians treated the six counties much more generously than before, readily funding improvements in the region’s social services and providing unionists with the constitutional guarantee they sought.

After 1945 it seemed possible that the resulting improvements might erode its continuing sectarian divisions and lay the foundations for political cohesion and stability.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

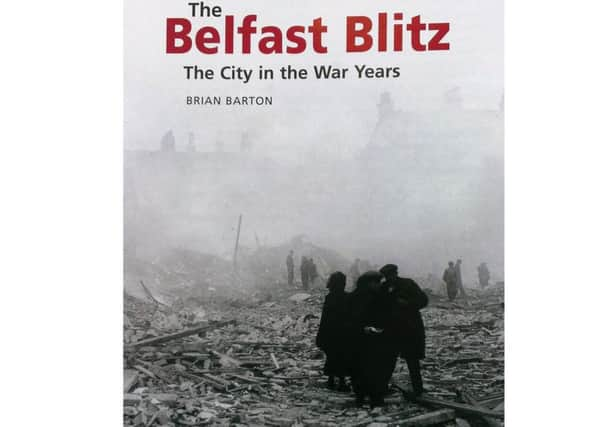

Hide Ad• ‘The Belfast Blitz: the City in the War Years’, by Dr Brian Barton, published by the Ulster Historical Foundation, 650 pp, £19.99