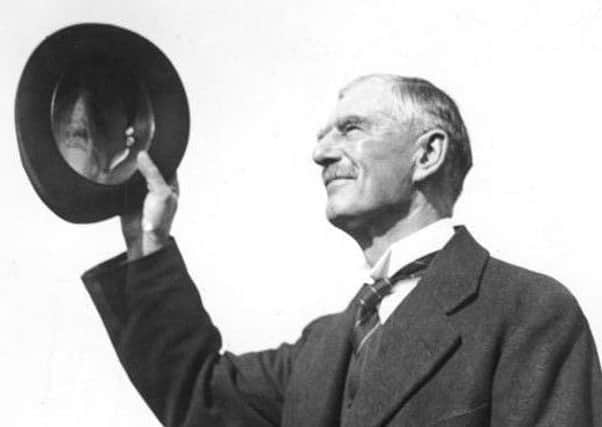

Chamberlain's appeasement of Hitler met little dissent from a public wary of war

After the annexation of Austria in March 1938, the next country in Hitler’s sights was Czechoslovakia. Czechoslovakia had a population of three million German speakers (formerly subjects of the Austro-Hungarian Empire) living within its boundaries, largely in the area adjacent to Germany which became known as the Sudetenland.

Hitler had previously stated: “It is not my intention to smash Czechoslovakia by military force in the near future.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy May 30 Hitler revised this to announce: “It is my unalterable will to smash Czechoslovakia by military action in the near future.”

Neville Chamberlain, the British prime minister, having never flown before, flew to Germany three times to try and negotiate a resolution of unfolding the Czech crisis and avoid war.

After meeting Hitler at Berchtesgaden on August 15, Chamberlain wrote to his sister: “In short I had established a certain confidence which was my aim and on my side in spite of the hardness and ruthlessness I thought I saw in his face I got the impression that here was a man who could be relied upon when he had given his word.”

Chamberlain met Hitler again at Godesberg on September 22 but Czechoslovakia’s fate was sealed at Munich on September 29 at a conference ostensibly organised by Mussolini but actually organised by Hermann Göring.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOver the heads of the Czechs and without their participation at the conference, the UK, France, Italy and Germany agreed to the immediate occupation of the Sudetenland by the Germans.

The British and the French shamefully bullied the government of Czechoslovakia into accepting the dismemberment of their country.

At Munich, Chamberlain thought he had obtained an international agreement from Hitler that Germany should have the Sudetenland in exchange for Germany making no further demands for land in Europe.

On his return to London, Chamberlain claimed that he had achieved ‘Peace for our time’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHundreds of thousands took to the streets to cheer Chamberlain. He appeared on the balcony at Buckingham Palace with the King and Queen. He was lauded in the City, in almost all the newspapers of the day and was accorded a standing ovation in the House of Commons.

Although retrospectively, Chamberlain and his colleagues have been scapegoated as ‘the guilty men’ (the title of an influential book written by three journalists – including Michael Foot – published in July 1940) who encouraged Hitler by their foolishness and cowardice.

The truth is the British people were resolutely opposed to rearmament and appeasement was hugely popular. Like Chamberlain, the British people viewed war with horror.

In a speech in Berlin Hitler declared: “I have no more territorial claims to make in Europe.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNeither Chamberlain nor Hitler’s claims had a long shelf-life. In less than a year the United Kingdom and France would be at war with Germany.

On March 15 1939 the Germans occupied Bohemia and Moravia and allowed the Slovaks to establish their own autonomous state.

As early as the autumn of 1938 Hitler was demanding the return of Danzig (an overwhelmingly German-speaking city under the jurisdiction of the League of Nations) and a transport route through the Polish Corridor which separated East Prussia from the rest of Germany.

Realising that he had been duped by Hitler, on March 31 1939 Chamberlain offered Poland a guarantee of military support should it be attacked. The French did likewise.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWas Munich a gigantic fraud? If so, who was conning who? Were the UK and France buying time for rearmament? Possibly but Chamberlain believed that Hitler was an honourable man with whom he could do business.

His weakness lay in his inability to comprehend the sort of man he was dealing with and his determination to pursue appeasement long after it was prudent to do so.

Daladier, the French prime minister, had no intention of taking any action without the UK and the UK had no intention of taking military action. On September 27 Chamberlain had said: “How horrible, fantastic, incredible it is that we should be digging trenches and trying on gas-masks here because of a quarrel in a far-away country between people of whom we know nothing.” Therefore the Czechs were on their own.

Hitler had a clearer vision of what he wished to achieve than either Chamberlain or Daladier.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHitler wished to incorporate the German-speaking population of the Sudetenland into the Third Reich.

By doing so he recognised that he would deprive Czechoslovakia of its defensible frontiers. He would also gain control of Czech raw materials and armaments.

Hitler regarded a well-armed Czechoslovakia, allied to France and the USSR, as a potentially serious obstacle to his ambition for German hegemony in Europe.

Some historians (and Robert Harris in his recent fictionalised account of the Munich crisis) speculate that if Hitler had have invaded Czechoslovakia, anti-Nazi politicians and military officers would have staged a coup and he was only saved by last minute diplomatic manoeuvring.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGeneral Ludwig Beck, chief of staff of the German Army, was adamant that Germany could not win a war fought over Czechoslovakia in 1938. Hitler dismissed Beck’s arguments as ‘childish calculations’.

Could the British and the French have intervened militarily to help the Czechs? On September 26 General Gamelin, the French commander-in-chief, pointed out that British and French forces, combined with those of the Czechs, were greater than those of the Germans.

On the Franco-German border, 23 French divisions faced eight German divisions.

The Wehrmacht was not yet the formidable and well-oiled military machine it was to become. During the Anschluss 70% of German military vehicles broke down on the road to Vienna.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEighty years ago the French army was widely regarded as the best in the world. It was large, well-armed and well-equipped. In terms of manpower and material it was at least the equal of the Germans.

In 1940 what was to make the difference was German superiority in operational deployment and use of tanks and planes.

But in 1938 the crucial factor is that the British and French simply lacked the political will and suffered from a misplaced military inferiority complex.