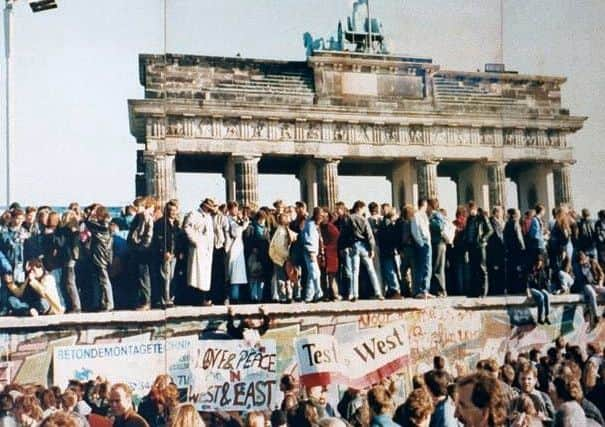

Fall of Berlin Wall one of most iconic moments in modern European history

The fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9 1989, like the storming of the Bastille in July 1789, is one of the iconic moments in modern European history.

Both events were more iconic than historically significant. While the Bastille may have been a convenient symbol of royal despotism in the centre of Paris, it was scarcely a credible one. At the time of its storming the Bastille contained only seven prisoners: four forgers, two lunatics and a libertine imprisoned at the request of his own family. French sources describe one of the lunatics as English whereas English sources describe him as Irish, He was actually Anglo-Irish. Ironically, those who stormed the Bastille initially forgot to free the prisoners because they were actually far more anxious to get their hands on weapons and gun powder.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Berlin Wall, on the other hand, genuinely symbolised the oppressive nature of the DDR (the German Democratic Republic). This grim edifice was erected in August 1961 to stem the tide of its citizens fleeing to the West in search of a better life. The DDR, the most rigidly conformist and most slavishly pro-Soviet state in the eastern bloc, was effectively a Gulag imprisoning its people in the heart of Europe.

The Berlin Wall was effectively breached some months before November 9 when in the summer of 1989 a reformist Hungarian government began allowing East Germans to escape to the West through Hungary’s newly opened border with Austria. By the autumn of 1989 thousands of East Germans had fled the DDR by this route. Nevertheless, the fall of the Berlin Wall symbolised the collapse of the Soviet bloc in eastern Europe and anticipated the disintegration of the USSR itself during the course of 1991.

The events of November 9 1989 in Berlin have a mildly farcical nature. On that evening Günter Schabowski, a high-ranking functionary in the Socialist Unity Party (the official name of the East German Communist Party), mistakenly announced in a televised news conference that the government would allow East Germans unlimited passage to West Germany, effective ‘immediately’. The authorities had in fact intended to require East Germans to apply for exit visas during normal working hours.

East Berliners widely interpreted Schabowski’s statement as a decision to open the Berlin Wall that evening. As a result huge crowds assembled at the wall and sought to cross into West Berlin.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCompletely unprepared, the border guards allowed them to do so. In a night of revelry tens of thousands of East Germans surged through the crossing points in the wall and celebrated their new freedom with rejoicing West Berliners.

On November 12 East German border guards stood aside as crowds on either side enthusiastically set about the 28-year-old wall’s demolition.

Why did the wall fall and why did the DDR collapse? Essentially the DDR’s collapse was triggered by the decay of the other Communist regimes in eastern Europe. For example, in Poland in August 1989, after a decade of political instability largely precipitated by the election of Karol Józef Wojtyła as Pope John Paul in 1978, General Jaruzelski, the country’s Communist leader, invited Tadeusz Mazowiecki, Lech Wałęsa’s principal advisor, to become prime minister of Poland, the first non-communist to lead a Polish government since the Second World War.

To take another example, in Hungary on October 23 1989, ironically the anniversary of the outbreak of the Hungarian uprising of 1956, the Hungarian People’s Republic (through the radical amendment of the country’s 1949 constitution) effectively abolished itself and the Hungarian Communist Party converted itself into a social democratic party operating in a multi-party state.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough at the beginning of 1989, as the regime planned its 40th anniversary celebrations, Erich Honecker, the DDR’s Neanderthal Stalinist leader, had boasted that the Berlin Wall would be still in place ‘in 50 or a hundred years’, pressure was building up within the DDR. From early September 1989 onwards there were huge and growing demonstrations, largely organised by the Protestant churches, on Monday evenings in Leipzig. The demonstrators called for democracy and free elections and, at this stage, ‘a path towards a better, reformed socialism’ rather than German unification.

The Politburo of the DDR did not lose the will to resist immediately because Honecker was replaced in mid-October by Egon Krenz, another younger but equally hard-line Communist.

However, the Politburo could not fail to realise that the DDR was in severe difficulty. The reforms of President Mikhail Gorbachev of the USSR had so appalled Honecker that he had banned the circulation within the DDR of Soviet publications which he viewed as dangerously subversive. Gorbachev, for his part in his book, ‘Perestroika’, had indicated that in his view Soviet hegemony in eastern Europe paid no dividends. When Gorbachev had visited East Berlin in early October 1989 to mark the 40th anniversary of the establishment of DDR, he urged reform on Honecker, telling him that ‘life punishes harshly anyone who is left behind in politics’ and that he could not count on Soviet tanks and troops to prop up the regime.

On October 8 Honecker ordered the Stasi to prevent further demonstrations. A bloodbath in Leipzig seemed virtually inevitable but Moscow intervened decisively, instructing the local Communist Party and the police that there must be no Tiananmen Square in Europe.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEarlier in the year Honecker had praised the Chinese authorities for defending socialism in Tiananmen Square, indicating his personal preference for a Beijing solution (a massacre) over a Warsaw solution (a peaceful accommodation). With the firm knowledge that there would be no Soviet intervention the DDR collapsed like a house of cards.

On December 2 the key clause of the East German constitution proclaiming the DDR a socialist state under the guidance of the Socialist Unity Party was deleted. On December 4 the Politburo and the Central Committee of the Party resigned. By December 6 Krenz resigned as head of state and the DDR was consigned to the dustbin of history.