Greysteel massacre: Priest recalls '˜cruelty and barbarity' of trick or treat killings

and live on Freeview channel 276

“It was very true of Greysteel that those who suffered the most were quickest to forgive, to look for peace,” Fr Stephen Kearney said as he reflected on the horrors of the shooting ahead of the 25th anniversary.

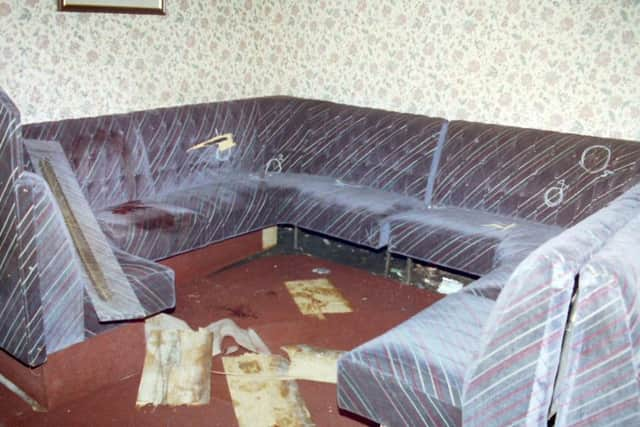

On October 30, 1993, loyalist gunmen entered a pub in the quiet, rural village in Co Londonderry during a Halloween party and, with the words ‘trick or treat’, opened fire.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe shootings at the Rising Sun Bar claimed the lives of seven people, and another who died from his injuries six months later.

Six of the deceased were Catholics, while two were Protestant.

The attack was claimed by a group styling itself ‘Ulster Freedom Fighters’ as revenge for the IRA attack on the Shankhill Road in Belfast days before.

It took place just before 10pm, when three gunmen — Stephen Irwin, Geoffrey Deeney and Torrens Knight — entered the busy pub. Irwin was armed with an automatic rifle, Deeney with a pistol, and Knight with a sawn-off shotgun.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt first, those inside believed the gunmen were playing a Halloween prank.

Irwin said “trick or treat” before opening fire. Deeney fired his pistol but it jammed after one shot, while Knight guarded the entrance.

The killings proved a catalyst for efforts to begin on the road towards peace, a fact tragically reflected on a memorial beside the scene of the shootings which reads: ‘May their sacrifice be our path to peace.’

Fr Kearney, who is now based in Co Tyrone, described his memories of the aftermath of the shooting in an interview with the News Letter ahead of the 25th anniversary of the massacre.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I was in a parishioner’s house, with people I knew, and their son was watching the TV while we were sitting around the fire,” Fr Kearney recalled.

“He came in to say there was a shooting in Greysteel. I was in Eglinton, and I headed down straight away.

“I went down there and saw the chaos.”

Fr Kearney said his colleague, the late Fr Jack Gallagher, had been the first person to enter the bar after the carnage.

“The place was lit up with the lights of cars,” he said. “The first person I saw coming out was Fr Jack Gallagher. I didn’t know how many were actually dead. We couldn’t have counted them.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe continued: “Fr Gallagher recognised some of them. They were people I knew.

“I had been chaplain at the hospital so I went up there. I was there for a few hours. One of the youngest victims, a young man named Mullan, himself and his girlfriend were in it — both of them were killed.

“He died while I was waiting to get into see him. I knew his father and mother reasonably well, I had only been in the parish a short while but he was one of the ones I did know.”

Fr Kearney recalled a “haze of grey dullness” hanging over the village in the immediate aftermath.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I remember certain moments,” he said. “One was when I was standing outside the chapel the next morning. I hadn’t been to my bed until that morning. I was over for the nine o’clock Mass in the chapel and I saw a few people standing there. They were barely able to speak, in shock. It was a dry, cool autumn morning. If I could paint the picture I wouldn’t have to describe it — everybody seemed to be grey, everything seemed to be grey, everyone seemed to have been wearing grey clothes. Everything was in a haze of grey dullness.”

He continued: “One of the people I saw was John Duddy whose wife had been killed.

“I had given her a lift home a few days before and she had arrived at my door with an apple tart as a reward for leaving her home. She was a lovely woman. They were there, a middle aged couple out for a drink that night, as were most of the people there. They were mostly older people.”

Asked how the community reacted to the terrible events that night, Fr Kearney said: “Everyone responded in a very personal way. The atmosphere that you would have picked up afterwards would have been a sort of a peaceful sadness.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I think, perhaps, it was because of the nature of the people who were there, they were very mature sort of people in their outlook on life and they had suffered so much.

“The people joined into their suffering. In the immediate aftermath there were some who found it hard to cope, who were saying things that wouldn’t have been normal for them to say, out of anger or hopelessness.

“But most were neither hating, nor angry, nor hopeless.”

He continued: “It has been said that the Troubles had its origin in Derry, but it had the beginning of its end in Derry. The media had a role to play in that. The cruelty of it, the sheer barbarity of it — trick or treat — that was well enough portrayed. It was really anti-human and it was portrayed as such.”

Fr Kearney added: “There was a strength that came out of the people when they felt least strong.”