The tale of two giants from Northern Ireland

Brendan, 66, was a perfectly normal schoolboy until he hit puberty and grew to a height of six foot seven. It was not until he was 18 that he found out he had a condition known as gigantism.

The Dungannon man told the News Letter: “It’s very much hereditary, but that doesn’t mean that all my family are big. The gene can be carried by people without their knowledge and passed on to the succeeding generation also without their knowledge.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“In every other respect they are 100% normal if there’s such a thing as normal, but they are carrying the gene. It does not affect them but it may affect their offspring.

“The condition may only develop for one in four or one in five of those who carry the gene. It’s a rare condition made even rarer by how it manifests itself. Why one person develops it and another doesn’t is yet to be discovered.”

Brendan now stands at six foot nine and a half: “I used to be six foot 10, but I’ve shrunk with age.”

He said that while his height presents practical difficulties, the condition also brings with it physical limitations: “If you think about what the heart is trying to do – pump blood around a huge frame – and that overworks the heart so it causes cardiac problems and breathing problems. You tire easily.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe continued: “For me, the condition came with the onset of puberty. When I was at school I was six foot eight. I grew a good foot in four or five years which is an extraordinary amount of growth when you think about it. In normal circumstances I probably would have been playing sports, but one of the side affects is that you have very little stamina and are unable to sustain vigorous physical activity for a period of time.”

He continued: “Insofar as I’ve earned a living, it hasn’t impaired me, but as I’ve grown older it has impaired my ability to get around. I get out of breath very easily so I would use a wheelchair.”

Brendan, who is one of eight children, has been married for 20 years and has two children of his own – twins Stephen and Michael, 33.

He said: “The twins are not carriers so that’s the end of the line in my immediate family. I have other brothers whose offspring carry the gene – my niece has the condition and her daughter has the gene as well. It’s very unscientific to say it’s a bit of a lottery but it actually is – the way in which it finds itself in different people’s bloodstreams.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Twins also runs in the family. My sister has twins, my great grandfather was a twin. I guess that’s another genetic condition.”

Brendan explained how the condition can also affect people later in life, even after they’ve stopped growing: “Acromegaly is the same condition as gigantism but because the body has done all its growing and the bones have fused it means that parts of their body grow outwards – they get wider feet, thicker fingers and toes and they develop growth on their chin and forehead. If you remember seeing Jaws in the James Bond films he is symptomatic of that condition.”

He added: “I wouldn’t change anything because life is a series of pluses and minuses. You have to play the hand that is dealt to you. How you do that is more important. You have to admire people born with a disability who still lead interesting and fulfilled lives.”

Brendan recently took part in a BBC NI documentary during which he tried to get a better understanding of his gigantism and help in the research into the condition.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTrue North: The Giant Gene goes out on Wednesday at 10.40pm on BBC One NI.

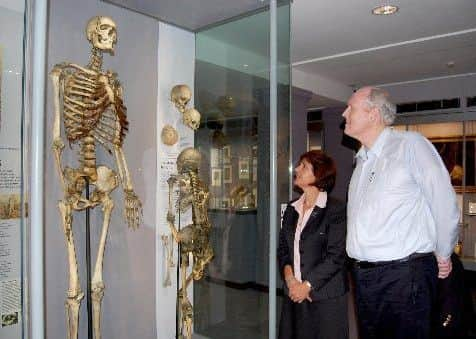

Meanwhile, a 250-year battle continues to bring home the bones of an Irish giant from Co Tyrone who has been kept against his dying wishes in London.

Thomas Muinzer, a lecturer at Stirling University who hails from Belfast, has researched the legality of the treatment of Charles Byrne’s skeleton by London’s Hunterian Museum.

Born in Co Tyrone in 1761, Byrne suffered from acromegalic gigantism, a condition causing him to grow to a height of nearly eight feet. After a successful run as a society curiosity in Georgian London, he fell into despair following the theft of all his savings.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith depression, TB and his worsening condition hastening his end, a dying Byrne told friends to weigh down his coffin and bury him at sea, afraid his body would be stolen for medical research.

When the sea burial occurred, surgeon John Hunter had bribed an undertaker to switch the corpse of the 22-year-old en route for dead weight and bring him the body. Afterwards, Hunter put Byrne’s skeleton on display.

Dr Muinzer – who maintains a blog called The Conversation – explained: “Today, that skeleton remains on display in London’s Hunterian Museum, named after the surgeon himself. But as the museum undergoes a period of closure for refurbishment, campaigners are calling for the release of the remains for burial. The Hunterian trustees have refused, arguing that the skeleton has important educational and research value.”

He added: “I have since researched the legality of the museum’s treatment of Byrne’s skeleton, finding that while its trustees arguably are treating the remains unethically, they are not behaving unlawfully.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The voices opposing the museum’s actions are getting louder and louder, and include the likes of author Hilary Mantel as well as several Irish politicians and even John Hunter’s biographer Wendy Moore.

“Now that the Hunterian has closed for refurbishment, the trustees have some thinking time. Do they respect the big Irishman’s last wishes, or continue to display his remains in a museum built as a memorial to the very man who stole them?”