Belinda Mulrooney - the Irish girl who became queen of the gold rush

Entitled ‘The Cremation of Sam McGee’, the poem opens with the lines: “There are strange things done in the midnight sun By the men who moil for gold.”

Moiling was an old-fashioned terminology for toiling, or working your fingers to the bone, and it wasn’t only men who ‘moiled’!

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMany women flocked to the Klondike too, to Dawson City, the epicentre of the gold rush.

A few tried panning for gold, some became so-called ‘shady ladies’ in Dawson’s Paradise Alley (the ‘entertainment’ tenderloin district); some became ‘hash-slingers’ (waitresses) or barmaids; some were washerwomen.

And some became entrepreneurs and businesswomen, digging gold not from Bonanza Creek but from the pockets and bank accounts of the miners who did the donkey work.

One such female entrepreneur was an Irishwoman, Belinda Mulrooney (or Mulroney in some accounts), from County Sligo.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShe was so successful that while still in her twenties, she was being hailed (by the up-market Scribner’s Magazine) as the richest woman in the Klondike. Others called her The Queen of the Klondike.

It was a fortune that began with three travelling trunks packed with…hot water bottles! But we’re getting ahead of the story.

Toronto travel writer Mitchell Smyth, who grew up in Ballycastle, has visited the Klondike several times, where he first learned of the Mulrooney story.

The story begins, he says, in 1872 when Bridget Mulrooney (the name change came later) was born in Carns, a rural townland about 15 miles north of Sligo town.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHer parents emigrated to the United States soon afterwards and Bridget was brought up by a grandmother. In her teens, she joined her parents in the coal mining country around Scranton, Pennsylvania, but life was too dull there for the Sligo-girl.

She took off for Chicago, where she ran a sandwich stand at the Chicago Exposition of 1893. She was worth several thousand dollars at the age of 21!

Next we find her on the steamer City of Topeka, which ran between San Francisco and the Alaskan Panhandle, where she added to her small fortune by bootlegging liquor.

The ship had no bar so Belinda (as she was now calling herself) made herself a long fur coat with a canvas lining.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the lining were pouches for 24 half-pint bottles, which she sold, at a handsome mark-up, to thirsty passengers.

Gold was discovered in the Klondike in 1897 and Belinda joined the rush, over the treacherous Chilcoot Pass from Skagway, Alaska, by foot, then down the Yukon River by raft to Dawson City, the centre of the action. But she didn’t travel light.

Looking ahead, she decided miners would pay a lot for a bit of warmth in the tent-towns of the ‘diggings’ so, assisted by two Indian guides, she carted three huge cases of hot-water bottles into Dawson, and sold them at a 600 per cent mark-up. Her fortune was growing.

Before long she owned a roadhouse where she entertained the likes of Jack London, the future author of gold rush novels.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is said that London modelled Buck, the dog ‘hero’ in his book The Call of the Wild, on Belinda Mulrooney’s pet dog.

A new film based on the book, starring Harrison Ford, has recently come out.

She worked the bar herself, listening to the gossip and shrewdly making notes for future action on new claims.

Within a year she had stock in a dozen mines and the money was flowing in.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

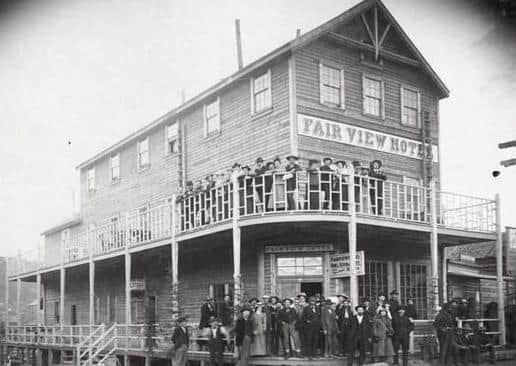

Hide AdShe built the Fairview Hotel, the best hostelry in Dawson, where miners paid big money to eat off linen tablecloths, drink tea from bone china and be serenaded by an orchestra.

By 1899, at the age of 27, she was being hailed as The Queen of the Klondike.

Then Cupid’s arrow struck this (in the words of one biographer) ‘short, dark, angular, masculine…hard-boiled’ woman.

Her suitor was one Charles Eugene Carbonneau, who introduced himself as a French count seeking investments in mines for an Anglo-French syndicate.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBelinda was so much in love that she wouldn’t listen to a French-Canadian foreman from the Bonanza mine, who positively identified ‘the count’ as a barber from Montreal’s Rue St. Denis.

They married in 1900. Belinda was 28. The ‘count’ and ‘countess’ honeymooned in Paris, where (says Canadian historian Pierre Berton) “they rode up and down the Champs-Elysses…with an Egyptian footman who unrolled a carpet of brilliant crimson whenever they stepped out.

They divorced in 1906, after Belinda discovered that ‘the count’ was fleecing her.

He died in 1919.

But she still had plenty of money left which she put it into real estate as the gold rush ebbed.

In 1910 she moved to Washington state, where she lived comfortably until her death in 1967, aged 95, with her memories of a very full life.