A civil rights activist who rejected violence and embraced causes across the sectarian divide

The late Kevin Boyle, who would become one of the world’s leading human rights lawyers and teachers, was the son of a taxi driver from Newry.

He liked to use the term ‘the three As’ to describe himself — activist, advocate, and academic.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe battle for civil rights in Northern Ireland was the first place where he played that role, as a founder and leader of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association.

As early hopes for peaceful reform were swept away by the Troubles, however, Boyle stood out, not only because of his resolute opposition to all forms of violence and his numerous crucial contributions to the search for peace, but because in his professional, political and personal life, he transcended the province’s sectarian divide.

Unlike some of his contemporaries, such as Michael Farrell or Bernadette Devlin, Boyle did not have a strong sense of Irish identity, despite his Catholic upbringing.

“I was never really happy with an exclusive identity,” he once told an interviewer. “I was happy to be part of both countries.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBoyle’s behaviour reflected this comfort level — not least when, at the height of the Troubles in 1976, and despite the risks involved, he married Joan Smyth, a Protestant from a small town near Omagh, and, after living in Belfast for a dozen years, left Northern Ireland to teach, first at NUI Galway, and then, for the last 20 years of his life, at the University of Essex.

Around the same time of his marriage, he also worked closely with fellow barrister Desmond Boal. A co founder with the Rev Ian Paisley of the Democratic Unionist Party, Boal had engaged in a sharp verbal duel with Boyle while questioning him during the Scarman Tribunal hearings on the roots of the 1969 violence.

Yet just a few years later, the two men, despite their political differences, teamed up to represent both young Protestants and young Catholics caught up in legal trouble because of the ongoing violence.

Boyle also embraced the cause of Jeffrey Dudgeon. It was Boyle who proposed to Dudgeon in 1975 that a case be brought before the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg challenging Northern Ireland’s law banning homosexuality.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough the case dragged on until 1981, the court ultimately accepted Boyle’s arguments. The decision led to the legalisation of homosexuality in the North, became the basis for its eventual legalisation in the Irish Republic, Cyprus, and other countries, and was even cite din a landmark gay rights case by the US Supreme Court in 2003 (Dudgeon later became a unionist politician).

Boyle’s earliest intellectual collaborators were also Protestants — Paddy Hillyard, then teaching at the New University of Ulster, and fellow Queen’s law professor Tom Hadden, who came from staunchly loyalist Portadown.

Together, they produced two important books — Law and State: The Case of Northern Ireland, in 1975, and Ten Years On: The Legal Control of Political Violence, in 1980.

Both books analysed the working of the courts and the behaviour of the security forces, and offered numerous practical suggestions for more humane and effective policies to deal with the Troubles.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTom Hadden, who was also the founder and long-time editor of Fortnight, went on to become Boyle’s partner in a series of papers, books and proposals that helped create the intellectual underpinning of the peace process.

The Boyle-Hadden critique of the 1984 New Ireland Forum, in which they dismissed the forum’s proposals as “totally unrealistic” and called recognising the right of the North’s unionists to remain in the UK while acknowledging the right of Northern nationalists to express their Irish identity, was embraced by the British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

The concept became a central feature of the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement and foreshadowed some of the key elements of the 1998 Belfast Agreement.

Boyle co-authored a report with a former British police officer on human rights and policing, which was submitted to Chris Patten as he conducted his review of the Northern Irish police in 1999. The document was also influential in helping to reform the police force. As the late Northern Irish civil servant Maurice Hayes told me, “They helped give us the language. This was important.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt a conference in 2008 to mark the 40th anniversary of the civil rights movement, Boyle stressed that the central feature underpinning all his work had been a belief in universal human rights, and he praised the formal protection of rights now enshrined in Northern Ireland. But he remained frustrated that, even with the end of the violence, the North was “still a divided society ... and perhaps even more divided”.

Moreover, for all his positive contributions, Boyle continued to carry the burden of wondering whether — however well-intentioned — his actions during the early days of the civil rights movement might have been responsible for helping to spark the bloodshed.

In the mid-2000s, he told an interviewer, “It wasn’t worth a single life. This is my own moral position.”

And just weeks before his death from lung cancer in 2010, he wrote to an old friend in Galway musing whether “if we might have had a more measured response,” the worst of the violence could have been avoided.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSuch introspection was typical of Boyle, a deeply sensitive man less interested in boasting of his many accomplishments than pondering what might have gone wrong — and finding ways to make things better.

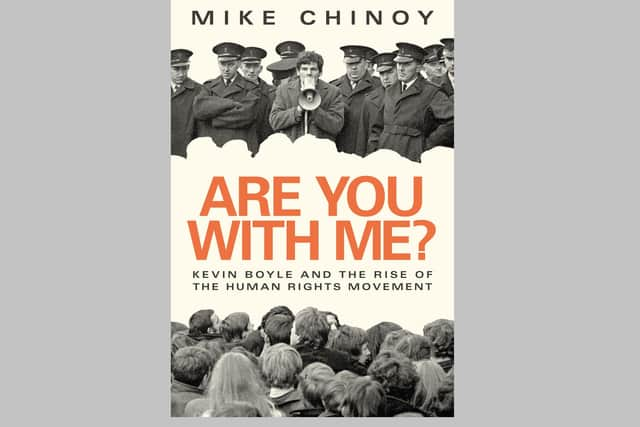

• Mike Chinoy was a foreign correspondent, serving as CNN’s first Beijing bureau chief and as Asia correspondent. He covered the Troubles in Northern Ireland in the 1970s and 80s. ‘Are Your With Me? Kevin Boyle and the Rise of the Human Rights Movement’ is published by Lilliput Press. RRP £18

——— ———

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

With the coronavirus lockdown having a major impact on many of our advertisers - and consequently the revenue we receive - we are more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSubscribe to newsletter.co.uk and enjoy unlimited access to the best Northern Ireland and UK news and information online and on our app. With a digital subscription, you can read more than 5 articles, see fewer ads, enjoy faster load times, and get access to exclusive newsletters and content. Visit https://www.newsletter.co.uk/subscriptions now to sign up.

Our journalism costs money and we rely on advertising, print and digital revenues to help to support them. By supporting us, we are able to support you in providing trusted, fact-checked content for this website.

Alistair Bushe

Editor