The British population of Gibraltar saw great risk in Brexit, unlike unionists in Northern Ireland

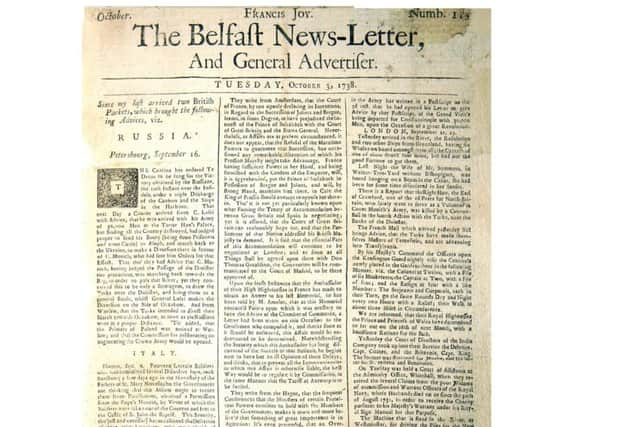

This week the first surviving editions of the oldest English language daily newspaper turned 280.

This newspaper was founded in September 1737, so reached its 280th last year, but the first 13 months of the paper are lost.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe first surviving News Letter, of October 3 1738 (October 14 in the modern calendar) reached the 280 milestone last Sunday, and all week we have serialised that edition, and the next one (October 6 1738, ie October 17 in modern dates).

One of the striking things about those early News Letters is the extent to which the geopolitical scene has not changed all that much.

There are reports about war between Russia and Turkey, between Christian and ‘infidel,’ reports from France and the Americas and Italy (the title used even though the country did not exist) and Germany (likewise the name was used but it didn’t exist).

There are reports on lotteries, and royal celebrations, and extreme wealth gaps (stories on the super rich and charity for the poor).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe papers are all lost for the rest of October 1738 and November and then return in December of that year. This December, we will serialise some more of those earliest surviving News Letters.

I have already read all of the late 1738 and 1739 News Letters when I serialised them five years ago, which was one of the most interesting assignments of my career.

A looming war with Spain dominates those early News Letters, and would culminate in the War of Jenkins’ Ear in late 1739.

There is much patriotic fervour in the run up to that conflict, given that the Spanish navy was seen to be aggressive with British ships, as the two sought to protect their territories in places such as the Caribbean, which is near to where Captain Robert Jenkins had his ear cut off by Spanish officials who boarded his boat.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere is also a lot of anxiety in the run up to the war, because there are many News Letter reports of the dreaded ‘press gangs,’ including in Waterford, which seized young men for military service.

And amid all the tensions, there are bitter disputes over Gibraltar.

In one 1739 report, the Spanish king has refused to pay money owed to Britain due to his fury at a British squadron, which “instead of remaining in either the port of Gibraltar, or that or Port Mahon, was lately almost constantly cruizing between them”.

Tensions over the Rock have waxed and waned in the near three centuries since that report, but they have never entirely gone away.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGibraltarians, who by an overwhelming margin want to stay part of Britain, were very uneasy about Brexit.

They feared that the Spanish tendency to make things difficult at the border, due to resentment at it being British, and which is often resolved via the European Union, would become permanently intolerable if the UK left the EU.

And so in the Brexit referendum of 2016, Gibraltar voted 96% in favour of Remain. They were not merely pro Remain, they were passionately so. They seemed to fear an existential threat from Brexit.

It is interesting to compare that response to the prospect of Brexit, and indeed the response of the unionists in Scotland, to that of unionists in Northern Ireland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn Scotland, the local Conservative leader Ruth Davidson, who has emerged in recent years as the great hope of unionism across the North Channel, campaigned for Remain.

Then, when she lost that argument, Ms Davidson loyally supported her prime minister and instead argued for the softest possible Brexit, in a way to mitigate the impact of a decision that she thought dangerous for the Union.

Now she is making clear that Northern Ireland should not get ‘special status’ because Scotland will want it too, and it might unravel the Union.

In other words, Gibraltar and Scotland perceived Brexit, in advance of the vote, as a threat to their position as British, and NI unionists did not. Indeed, most NI unionists still do not perceive such a threat.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd yet it seems that perhaps the greatest threat of damage to the Union is in fact here.

Britain and Spain have struck a deal over Gibraltar. One British politician familiar with the territory told me last night that he attributed this success to “the energetic and diligent application to this process by the erudite Gibraltar chief minister Fabian Picardo”.

In Scotland meanwhile, the Scottish nationalists have not yet made the breakthrough that they thought they would as a result of Brexit.

In Northern Ireland, however, unionism has been clobbered by the backstop of last December, although you would barely have any sense of that among unionist voters or politicians until recent weeks.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the start of the Brexit referendum campaign, unionism was much more split on the prospect of quitting Europe than it was by polling day in June 2016.

At first unionism was only narrowly in favour of Brexit, and was split almost 50/50 on the topic, but as the election day got closer it swung noticeably behind it, perhaps 80/20 (I think it is because of the constitutional divide, and Brexit became a symbol of Britishness).

Those unionists who backed Remain were mostly in the Ulster Unionist Party, and few of them actively campaigned against Brexit.

On election night, I concluded that Brexit had won early on in the count, when I knew that turnout was high in loyalist estates and when I saw Sunderland’s heavier than expected vote for Brexit (I then assumed my conclusion was wrong because the polling expert Peter Kellner said Remain had won).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne thing that people who sneer at unionists do not understand is that the loyalist working classes fundamentally see the world in a similar way to the working classes who backed Brexit in other British cities such as Sunderland.

That is why there is little backlash in unionism against Brexit. Insofar as most loyalist voters think closely on the topic, they assume they are being cheated of Brexit.

There is still no sense of great danger, probably because the major constitutional implications of some outcome such as Northern Ireland staying forever aligned to EU regulations are quite hard even for those of us who follow it closely to grasp.

We might see the beginnings of a split within unionism today at the Ulster Unionist conference. Their leader Robin Swann is seemingly now calling for a softish Brexit, although he has not spelt out what that means.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe DUP, meanwhile, are now almost trapped in alliance with Brexiteers, hoping that if the latter prevail they will remember such support. It is a high risk strategy.

• Ben Lowry (@BenLowry2) is News Letter deputy editor