Why did so many southern Irish fight against Hitler?

Nobody can sure of the actual number; an official count puts it at just under 43,000, but the true figure is almost certainly much higher as many who enlisted wile resident in Britain were not listed as Irish.

If we are to consider all men and women who donned British uniforms during the conflict, including those in the Merchant Navy, nurses attached to the various military services and those in auxiliary roles, the numbers are probably in excess of 100,000.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis would be an extraordinary high number from a neutral state, one in which memories of the bitter Anglo-Irish conflict were still raw and taking into account that the Irish government actively discouraged its citizens from joining the British military. What motivated so many to defy them and fight on the side of the old enemy?

The recruits can be classified into a number of groups. Firstly, there were those who had already enlisted prior to 1939. Traditionally, the Irish were disproportionately represented in the British Army and independence in 1922 did not greatly alter this. The hungry thirties drove thousands to Britain in search of work and for many the Army was the only available option during the depression.

Also, there was the desire of the young for adventure. The late Jack Harte, who later in life was to become an Irish Labour Party senator, described in his memoir To the Limits of Endurance how, in 1937, “with little to do in a bleak and dreary Dublin, I was hungry for adventure”. Just 16, with not a penny in his pocket, he stowed away on the Liverpool boat to enlist, adding two years to his age.

He wasn’t alone in taking this route, for he was following the example of hundreds, including a number of his former Dublin inner-city mates. He saw action in the Middle East, Malta and Greece before being captured while serving with the Special Boat Service, the forerunner of the SAS.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEntrants into the officer ranks frequently came with a family tradition of service, most notably the Anglo-Irish, but by no means confined to them. Many Catholic families too had served.

When Conn Glanton from west Cork enlisted in the Royal Navy in 1939 he was following the example of his father and three uncles. He later rose to be become Lieutenant Commander of the fleet.

A fellow county man, Willie Murphy, was the first RAF bomber wartime pilot to die in the combat when his plane was shot down just a day after war was declared. Mike Casey, a former student of the Jesuits in Clongowes Wood, also became a pilot in the RAF. He was one of fifty of the ‘Great Escapers’ from Stalag Luft III to be murdered by the Nazis after recapture.

Reservists, many of them veterans of the First World War, formed another group. It would have been easy for those resident in the South to ignore their recall, and some did, but most returned to arms without hesitation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAmong them was Captain John McGrath, a Roscommon farmer’s son, who left his prestigious job as manager of Dublin’s Theatre Royal. He was one of the 40,000 who didn’t make it to the boats at Dunkirk, was captured and spent most of the war in SS concentration camps, before becoming part of a group of VIP hostages during the final weeks of the war. He was the inspiration for my book, Dachau to the Dolomites.

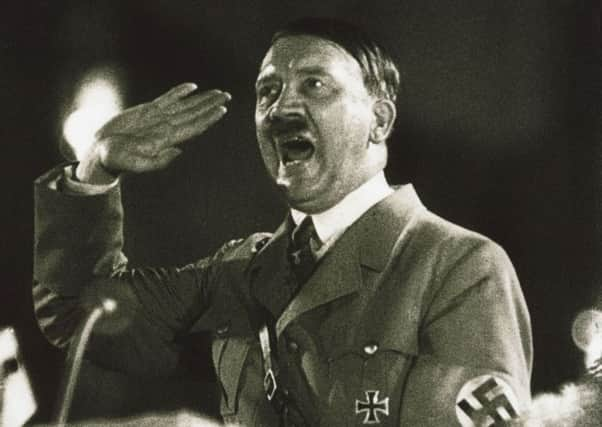

There were also those, which included many of the above, who were primarily motivated to fight against Hitlerism and Fascism. It’s impossible to know how big a factor this was as the evils of Nazism were only to become fully evident later.

Nevertheless, some had learned enough to cast aside any lingering Anglo-phobia in order to join the fight. Among them were thousands who deserted the Irish Army to join the British forces during the war, mostly after the direct threat to Ireland receded.

As they furtively crossed the border to enlist in Enniskillen and elsewhere, they knew more than most the dangers they were facing. The de Valera government penalised them by withholding all accrued benefits, including pensions, and barring them from all state employment for a period of seven years after their return.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen, at the end of the war, it was put to Oscar Trainer, the Minister for Defence, that these men’s real crime in his eyes was not their desertion, but their willingness to fight with the Allies, he sarcastically asked whether instead they should be welcomed back with bands and banners.

The story of southern participation in the Second World War has only recently began to be told. In the immediate post-war era, the Dublin political establishment, still largely composed of IRA veterans of the War of Independence, tended to regard references to the matter as a reproach, or an example of recidivist west-Britism.

For the more strident republicans it was treason. Those who returned to Ireland after the war tended, like most survivors, to be reluctant to talk of their exploits, a reticence reinforce by this environment.

Almost all the Irish Second World War veterans have now passed on and we can only hope that their stories are known to their decedents. Historians Richard Doherty and Stephen O’Connor as well as Kevin Myers deserve praise for their research in this area.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMost welcome too is the work of Dan Harvey, a retired Lieutenant Colonel of the Irish Army, who has recently had two excellent books published, A Bloody Dawn and A Bloody Week dealing with the Irish contribution to D-Day and Arnhem respectively.

The contribution of Irish volunteers in the war against Fascism deserves to be honoured. There is no credible evidence that their involvement was the cause of any diminution in their sense of Irish nationality or even, for most, a rejection of Irish neutrality.

Perhaps, like Frances Ledwidge, a nationalist poet who died at the front during First World War, they joined Britannia’s fight because she stood “against an enemy common to our civilisation”.

l Tom Wall is author of Dachau to the Dolomites – The untold story of the Irishmen, Himmler’s special prisoners and the end of WWII published by Merrion Press.