Imposing Ulster Tower at Thiepval a fitting memorial to sacrifices of Somme

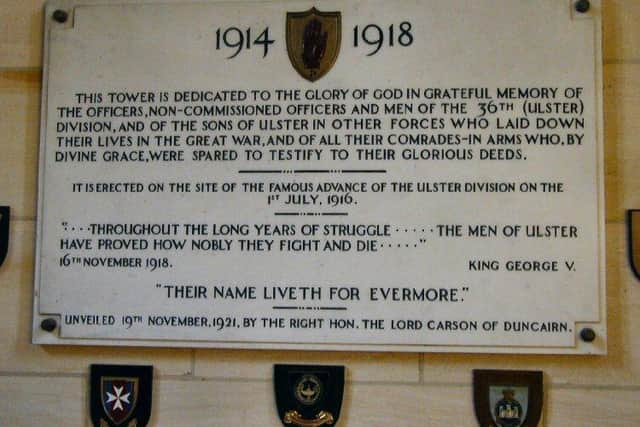

The inscription plaque at the Ulster Tower at Thiepval, Northern Ireland’s National War Memorial, explains its purpose: ‘This Tower is Dedicated to the Glory of God in grateful memory of the Officers, Non-Commissioned Officers and Men of the 36th (Ulster) Division and of the Sons of Ulster in other forces who laid down their lives in the Great War, and of all their Comrades-In-Arms who, by Divine Grace, were spared to testify to their glorious deeds.’

Although the memorial was to have been unveiled by Lord Carson, it was unveiled by Field-Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, former chief of the Imperial General Staff (the professional head of the Army), on November 9 1921 because Carson was ill. The tower was dedicated by the primate of All Ireland, the moderator of the Irish Presbyterian Church, and the president of the Methodist Church in Ireland. The ceremony was also attended by French dignitaries.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the time the tower was described as the most imposing monument on the Western Front. Sir Henry Wilson thought it was ‘a beautiful building’. It was certainly one of the earliest memorials erected on the Western Front, if not the first.

A memorial was first suggested by Sir Edward Carson, the Unionist leader, as early as November 1918. Carson had visited and walked over the battlefield in 1917 and the experience had a profound effect on him.

A meeting was held in Belfast on November 17 1919 to discuss a memorial in France. Sir James Craig, who would become Northern Ireland’s first prime minister in June 1921, reported that he and Wilfrid Spender, the future secretary of the Northern Ireland cabinet, both of whom had served in the Ulster Division, had attended a Royal Academy exhibition of designs for war memorials but they were not impressed by any of the designs they saw.

An architectural competition was briefly considered but Craig’s perusal of the stringent rules laid down by the Royal Institute of Architects deterred him. The expense was off-putting and there was no guarantee that he or his colleagues would be happy with the outcome.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCraig then came up with the inspired suggestion that the memorial should take the form of replica (or a close copy) of Helen’s Tower which had been erected by the future Marquess of Dufferin and Ava at Clandeboye as a tribute to his mother.

Helen’s Tower, a Scottish baronial style structure, was a very appropriate choice because many of Ulster Division’s troops received their preliminary training in its shadow on the Clandeboye estate in 1914 and early 1915.

The Ulster Tower is usually regarded as being sited on the German front line, close to the formidable Schwaben redoubt. According to Martin and Mary Middlebrook’s Somme Battlefields, it is ‘on the extreme northern edge of the advance that day’. They also assert it is one of the few places on the Somme where a divisional attack can be seen almost in its entirety from one spot.

On July 1 1916 the division attacked astride the River Ancre, a tributary of the Somme. Although the battalions attacking north of the Ancre were wiped out within half-an-hour, south of the river the Ulster Division achieved stunning success. Despite facing one of the strongest portions of the entire German front, the Ulster Division captured a long section of the German front line. Pressing forward, the men stormed and took the Schwaben Redoubt, a fearsome parallelogram of trenches, dugouts and machine-gun posts and possibly the most formidable German position on the whole front, and were the only division to reach the second German main trench system.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTheir success was not matched by the divisions on either flank (the 29th to Ulster’s Division’s left and the 32nd to its right) or indeed elsewhere. Therefore, they pushed a deep salient into the German lines. It was thus that the division fell victim to its own success.

Surrounded on three sides and subjected to strong and repeated German counterattacks, the division grimly held its ground. Although beating off each successive attack, each one left the division with more dead, fewer defenders and less ammunition. After 14 hours of heavy fighting during which no help was received from the divisions on either side, the order was given to withdraw and return to the former German front line for a last stand. Ironically, it was when the withdrawal was well under way that reinforcements arrived, but it was too late to prevent the Schwaben Redoubt falling back into the hands of the Germans. Reluctantly, hard-fought-over territory was abandoned and would not be retaken by British troops for many months.

The division’s exploits attracted much praise. The Times correspondent, Philip Gibbs, wrote: ‘The attack of the Ulstermen was one of the finest displays of human courage in the history of the world’. In a letter to General C H Powell, the Ulster Division’s commander at the time of its formation, Major H Singleton of the division’s field headquarters observed: ‘I have served with Regulars, Volunteers [and] Colonials, but never in my life have I ever seen such deeds of heroism and gallantry as those displayed by Ulstermen. They may be equalled but cannot be surpassed.’

Nine Victoria Crosses were awarded for acts of valour on July 1. Men of the Ulster Division won four of these. Of those, three were awarded posthumously.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Ulster Division’s casualties were heavy. According to Officers Died in the Great War (London, 1922) and Soldiers Died in the Great War (London, 1922), 1,944 members of the Ulster Division were killed or died of wounds on July 1 1916. The division was relieved on July 2, having suffered 5,104 casualties of whom 2,069 died.

Why does the Battle of the Somme remain so important? As the late Professor Keith Jeffrey explained in ‘1916: A Global History’, both the Easter Rising and the opening day of the Battle of the Somme ‘became sanctified in their respective Irish political traditions and they have been stitched into the creation stories of both the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland’.