Remembering the hardships of Irish soldiers '“ at the front and at home

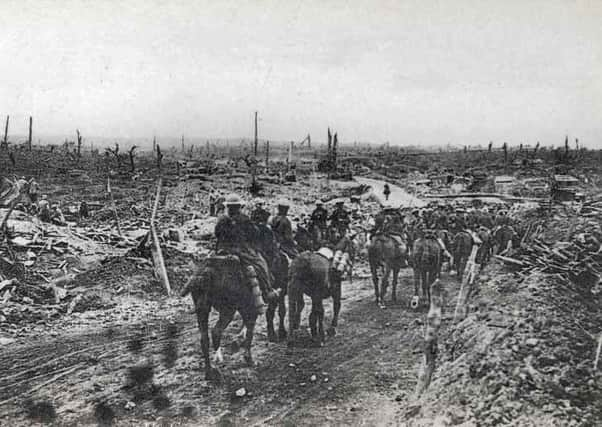

Like the 36th (Ulster) Division, the 16th (Irish) Division also fought and distinguished itself in the Battle of the Somme.

Despite its name, the 16th (Irish) Division was a division in which Ulstermen were strongly represented.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Division’s 49th Brigade consisted of four Ulster-based battalions: the 7th Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, the 8th Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, the 7th Royal Irish Fusiliers and the 8th Royal Irish Fusiliers.

The Division’s 48th Brigade included one Ulster-based battalion and two battalions with a strong Ulster component: the 7th Royal Irish Rifles, the 6th Connaught Rangers and the 6th Royal Irish Regiment.

The Commanding Officer of the 6th Connaught Rangers was an Ulsterman: Lieutenant-Colonel Jack Lenox-Conyngham of Springhill, Moneymore.

Within the ranks of his battalion were some 600 supporters of Joe Devlin, the Nationalist MP for West Belfast.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe 6th Royal Irish Regiment had several hundred men from Counties Londonderry and Tyrone within its ranks.

The 16th (Irish) Division did its fighting on the Somme between 5 and 9 September 1916 rather than on 1–2 July, and at Guillemont and Ginchy rather than at Thiepval.

The 16th (Irish) Division casualty figures were almost as grim – although spread over a slightly more extended period – as those of the Ulster Division.

Over 10 days the division sustained 4,230 casualties.

The 6th Connaught Rangers lost 23 officers, including its commanding officer, and 407 men, while the day after the Battle of Ginchy the 7th Leinsters could muster only 15 officers and 289 men.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDescribing the battle for Guillemont, a Connaught Ranger observed: “We swept through the Germans like the Dublin Mail going through Westport.”

Of the capture of Ginchy, a village which stood on a hill 500 feet high, war correspondent Philip Gibbs reported that the 16th (Irish) Division’s feat “ought to be recorded in heroic verse rather than in a journalist’s prose”.

The Easter Rising had no impact on the reliability and performance of these men.

Private A. R. Brennan of the 2nd Royal Irish Regiment recalled: “It was while we were stationed in one quiet little hamlet that the news came through of the Irish Rebellion.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Although we were all mildly interested, nobody took the thing seriously.”

Stephen Gwynn, the Home Rule MP for Galway who had enlisted in January 1915 in the 7th Battalion of the Leinster Regiment and had secured a commission in the Connaught Rangers in July1915, recorded that the Connaught Rangers were furious about the events of Easter week in Dublin because “they felt they had been stabbed in the back”.

In September 1916 the 8th Munster Fusiliers found themselves at the front opposite two large German placards. One announced the fall of Kut to the Turks, the other read: “Irishmen! Heavy uproar in Ireland. English guns are firing at your wifes [sic] and children.”

According to the regimental history, the Munster Fusiliers responded by singing: “God save the King” and, when they managed to capture the placards, they presented them to King George V.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUltimately the Easter Rising did make a profound difference. The Ireland which soldiers from a nationalist background left in 1914 was a radically different place from the one to which they returned in 1918 or 1919.

On September 20 1914, John Redmond, the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, speaking at a review of Irish Volunteers at Woodenbridge in County Wicklow, had told them they had two duties.

First they had a duty to defend “the shores of Ireland” and, second, to “account yourselves as men, not only in Ireland itself, but wherever the firing line extends in defence of right and freedom and religion in this war”.

On their return, far from being welcomed as heroes, they were viewed with suspicion.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTheir courage and their sacrifice were completely overshadowed by the events of Easter week.

Some of them indeed were murdered as “British spies”.

In Our War: Ireland and the Great War (2008), Jane Leonard has observed that between 1919 and 1924 more than 120 civilian veterans of the Great War were killed by the IRA or by anti-Treaty republicans in the Civil War.

She concludes that most were killed “simply as retribution for their part in the war”.

As Stephen Gwynn observed: “And when the time came to rejoice over the war’s ending was there anything more tragic than the position of men who had gone in their thousands for the sake of Ireland to confront the greatest military power ever known in history, who had fought the war and won the war, and now looked at each other with doubtful eyes?”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Ireland to which they returned viewed them as being on “the wrong side of history”.

On September 3, 1914 Edward Carson, the Unionist leader, had said that England’s difficulties were not Ulster’s opportunity: “However we are treated, and however others act, let us act rightly.

“We do not seek to purchase terms by selling our patriotism.”

Carson urged members of the Ulster Volunteer Force to “go and help save their country and their Empire”.

They were to go and “win honour for Ulster and Ireland”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSoldiers with an Ulster, unionist background found themselves on “the right side of history” – unless they had the misfortune to be from Cavan, Donegal or Monaghan.

The closing words of Captain Wilfrid Spender’s eyewitness account of the Battle of the Somme did prove prophetic: “The Ulster Division has lost more than half the men who attacked and, in doing so, has sacrificed itself for the Empire which has treated them none too well.

“The much-derided Ulster Volunteer Force has won a name which equals any in history.

“Their devotion, which no doubt has helped the advance elsewhere, deserves the gratitude of the British Empire. It is due to the memory of these brave fellows that their beloved Province shall be fairly treated.”