Son of Ulster parents alerted the world to Serbia's typhus tragedy

Almost one quarter of the country’s male population aged between 15 and 50 died, tragically augmenting Serbia’s previous, appalling, statistics borne of two Balkan Wars in 1912-13.

The autumn of 1914 added endemic typhus to Serbia’s woes.

Dr Trew’s little-told story of Ulster’s medical aid to Serbia, inspired by artefacts, documents and diaries contributed by the public to the Living Legacies 1914-18 Engagement Centre (see http://www.livinglegacies1914-18.ac.uk/) made reference to British and Irish newspapers reporting widely on the Serbian typhus epidemic, initiating an urgent call for relief aid.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut after the war, the heroic Serbian medical relief campaign was soon almost forgotten.

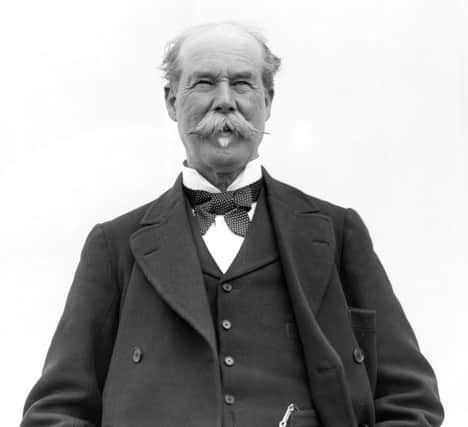

One of Serbia’s greatest champions was the well-known businessman Sir Thomas Lipton, who journeyed there to make the world aware of the tragedy that was unfolding, and thus to raise funds for relief aid.

Sir Thomas wrote in a British Red Cross Society pamphlet - “the warrior nation whom the might of Austria could not subdue is likely to be overborne by an invisible enemy - typhus.”

Sir Ralph Paget, formerly the British Minister to Serbia, became commissioner for British relief units. His wife, Lady Leila Paget, who had nursed in Belgrade during the Balkan war in 1912, became the administrator of the First Serbian Relief Mission, establishing a hospital at Skopje.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMedical relief units from several allied countries began arriving in late October 1914, among them a party of six British doctors including surgeon James Johnston Abraham from Coleraine.

In an edition of the Daily Telegraph on March 24, 1915, Sir Thomas Lipton described a Serbia in the throes of a terrible typhus epidemic such as “no country has ever been attacked before”.

Lipton, the founder of the Lipton tea brand, started a small grocer shop in Glasgow in 1871 which expanded to some 200 stores.

His family, variously spelt ‘Lupton’ or ‘Lopton’ in its earliest records, were already well-settled in County Fermanagh by the middle of the 17th Century.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThomas Lipton senior and wife Frances (née Johnstone) left Shannock Mills, near Clones, late in 1844 or early in 1845 and by late 1847 were living in Glasgow, where Thomas junior was born in a four room tenement on May 10, 1850.

He left school at 10 and worked as a cabin boy on the Burns shipping Line between Glasgow and Belfast.

At the age of 15 Thomas stowed away on a ship to America and worked first as a farm labourer and then in a grocer’s shop in New York.

Five years later he was back in Glasgow opening his first shop, starting him on his way to becoming a top entrepreneur, yachtsman and marketing guru, as well as an extremely generous benefactor to the sick and the poor.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMost of his countless donations were carried out anonymously and the sheer scale of his benevolence only became apparent after his death.

There are many intriguing tales about Lipton’s flair for marketing.

On a voyage to Ceylon in the late 1880s with a cargo of tea his ship ran into trouble.

The crew began jettisoning cargo to lighten the load.

Despite the imminent danger of sinking, Thomas dashed below deck, grabbed a brush and some paint, and daubed ‘Use Lipton’s Tea’ on the crates that were being thrown overboard!

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter his WWI expedition to Serbia Thomas wrote a letter in the Daily Telegraph in 1915 arguing that the typhus epidemic was a “worse fate for the Serbian people than annihilation by the enemy.”

He described the desperate need for aid.

“No one could help being appalled at the terrible epidemic of typhus that is torturing the life out of this little nation.”

Thomas described the daily traffic jam of ox-wagons at a hospital door where “men in the delirium of typhus were laid there to die because there was no room for them inside.”

“Multiply this by a thousand cases,” he wrote “and you have Serbia as it is today…. It is a plague such as the world has seldom known.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe told of the wife of a British army chaplain who had to deal with 600 sick-beds without a single doctor or nurse to help and hardly any provision.

“It is a touching act of humanity,” he added “that help came from some of the Austrian prisoners of war.”

There was no room in the cemeteries for all the dead.

“Typhus carts, drawn by oxen, rumble through the streets,” he wrote “bearing their burden of men raving in fever and delirium. On the street pavements I saw white-faced men sitting down and shivering in the early throes of disease…unable to drag themselves to shelter.”

“What is happening to the women of Serbia I dare not think,” his letter continued. “In all the hospitals of Serbia I did not once see a woman patient. The hospitals are all filled with men as there is no room for women, who, I fear, must die in their own homes for want of doctors or medicines to save them.”

During his expedition Thomas asked only for modest accommodation and requested the same food as regular Serbs labouring under wartime conditions.