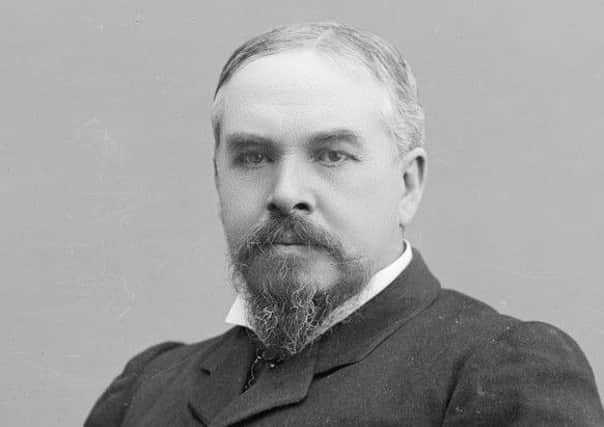

Ulster-born politician who helped New Zealand women secure the vote

This year marks the centenary of some women securing the vote at parliamentary elections in the United Kingdom. However, as early as 1893 all New Zealand women were given the right to vote in parliamentary elections.

The man primarily responsible for New Zealand women securing the vote was an Ulsterman, John Ballance – New Zealand’s 14th premier (or prime minister).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs a liberal, he was a great admirer of the philosopher J S Mill and his book, ‘The Subjection of Women’.

Writing in the Evening Herald of January 6 1874, Ballance noted: ‘Mill … reasoned that not until women had equal political rights would many of the grosser evils which afflict society be removed … in every sense the interests of civilisation seem to demand that women shall be placed on a perfect equality with men. This equality should proceed to the holding of property in her own right, the exercise of the electoral franchise, and the practice of the learned professions.’

Apart from Mill, Ballance’s politics were shaped by his mother; Ellen, his politically astute second wife; and Julius Vogel, New Zealand’s eighth premier.

In 1879 he had unsuccessfully attempted to amend an Electoral Bill to enfranchise women. Supporting an Enfranchising Bill of 1890, he declared: ‘I believe in the absolute equality of the sexes, and I think they should be in the enjoyment of equal privileges in political matters.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe following session, he introduced a new bill containing the female franchise from the outset. The legislation became law in September 1893.

John Ballance was the eldest son of Samuel Ballance, a fairly prosperous Glenavy tenant farmer, and his wife Mary McNiece. John was born in the townland of Ballypitmave, about two-and-a half miles east of the village. He was educated at Glenavy National School and Wilson’s Academy in Belfast. Aged 14, he was apprenticed to a Belfast ironmonger and subsequently became a clerk in a Birmingham firm of wholesale ironmongers.

A voracious reader, the young Ballance developed a keen interest in literature and politics. He took his politics from his liberal mother who had a Quaker upbringing rather than his conservative Church of Ireland father. Ultimately Ballance rejected Christianity altogether, becoming a free thinker.

Having married Fanny Taylor in Birmingham in 1866, Ballance and his wife emigrated to New Zealand, principally because of his wife’s delicate health. He intended to enter business as a small jeweller and did so briefly but soon turned to journalism. In 1867 he founded the Evening Herald (which in 1876 became Wanganui Herald), of which he became editor and remained chief owner for the rest of his life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe served in the Māori war of 1867, raising a volunteer cavalry troop and securing a commission. He was deprived of his commission for criticising the management of the campaign in his newspaper. Despite his dismissal, he was awarded the New Zealand Medal because he had served with distinction in the field.

In 1868, Ballance’s first wife died aged 24. Two years later, he married Ellen Anderson, the daughter of a Wellington architect with Co Down antecedents.

In 1872 Ballance put his name forward at a parliamentary by-election for the seat of Egmont but withdrew before the vote. Three years later he entered Parliament as MP for Rangitikei. He had two planks in his electoral platform: the abolition of the provinces (which was accomplished in 1876) and the provision of free education. After only two years in Parliament he entered the Cabinet of Sir George Grey and served as minister of customs, as minister of education (in which role he was not a great success) and later as colonial treasurer.

In 1879 he was elected to represent Wanganui but lost the seat by four votes (393 to 397) in 1881. He was returned to Parliament for Wanganui in 1884. He entered Robert Stout’s Cabinet, becoming minister of lands and immigration, minister of defence and minister of native affairs (the remit of which included relations with the Māori).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn his role as minister of lands, he encouraged intensive settlement of rural areas, aiming to increase the number of people leaving the cities to ‘work the land’. His system of state-aided ‘village settlements’ by which small holdings were leased by the Crown to farmers met with success.

Despite his desire for increased settlement of government-held lands, he strongly supported the rights of the Māori to retain the land they still held – at a time when most politicians believed that acquisition of the Māori land was essential to increasing settlement. He also reduced the government’s military presence in areas where tension with the Māori existed, and made an attempt to familiarise himself with Māori language and culture.

Stout’s government lost the general election of 1887 but Ballance’s personal popularity remained undiminished.

After a brief period of illness and political inactivity, Ballance returned to become leader of the opposition in July 1889.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe following year Ballance led a loose coalition of liberal politicians – which became the Liberal Party – to victory in the general election. A number of features of his premiership merit mention. He was responsible for the introduction of a progressive land tax and progressive income tax and (posthumously) extending the franchise to women. By presiding over a period of increasing prosperity Ballance earned himself the nickname ‘the Rainmaker’.

In 1893 Balance died of cancer at the height of his popularity and power but not before laying the foundations of labour reform and the beginnings of the welfare state in New Zealand.

As a politician, John Ballance exhibited kindness, courtesy, consideration and patience. He was widely acknowledged to be a man of great honesty and integrity. While he lacked charisma and was not a great public speaker, he was an extremely accomplished politician.

Like all successful politicians, in the opinion of Dr Timothy McIvor, his Ulster-born biographer, he was ‘a pragmatist rather than an idealist’. The fact that New Zealand’s next four prime ministers would come from his Liberal Party forms a not inconsiderable part of his political legacy.