Unseen effects of IRA school bus blast resonated for decades

A bomb placed on a school bus in Fermanagh 30 years ago today may not have claimed the lives of its driver and passengers, but the unseen impact of the blast would resonate for decades to come.

For the injured driver Ernie Wilson, the mental anguish of such a close brush with death, and the trauma it caused his family, remains ever-present.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor one of the passengers who escaped injury – a young Enniskillen Collegiate pupil and future Northern Ireland first minister – her close encounter with IRA violence would help instil a steely resolve to ensure the terrorists would not achieve their ultimate aims.

The bus driven by the part-time Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) soldier was pulling away from picking up pupils Arlene Foster and Gillian Latimer in Lisnaskea when the hidden explosive device detonated.

It was just after 8am on June 28, 1988 and the bus was much less full than normal due to exams taking place.

The force of the blast destroyed the front of the bus, ripping out the floor pan and destroying many of the seats.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDespite being partially deafened and temporarily blinded by the explosion, Mr Wilson responded to cries for help from the main body of the vehicle and managed to resuscitate the critically injured Miss Latimer.

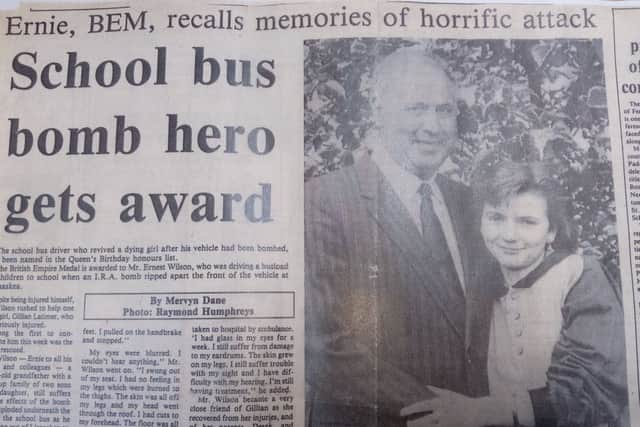

His heroic response was recognised with the award of the British Empire Medal (BEM) but life would never be the same again.

“It was coming to the end of the term and although I would normally have about 70 children on that bus, that day I didn’t have more than about 20 because they were only doing exams ... they were winding down.

“I lifted the first ones at the High School gates, the next one was Arlene Foster and Gillian Latimer, then I came down to the Diamond and lifted a few more. Then I lifted the rest at the factory gates at Sylvan Hill.

“I headed back again and next thing I heard was ‘bang’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“All I could see was what looked like lightning, and then everything went so silent. I couldn’t hear and I couldn’t see.

“At first I thought my legs were off because I couldn’t feel anything. But there was a small handbrake I was able to pull on and the bus stopped.”

It was only when the injured driver tried to turn around to look back down the bus that he realised his legs were still intact.

“I could partially see out of one eye and all I could see was windows blown out and there was no floor, and that was a 40ft bus.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Arlene Foster said to me, ‘Ernie, Gillian’s injured’. I got them all out and a crowd had started to gather. I got the hold of Gillian and got her to the back and put her along the back seat.

“I looked at her arm and could see straight through it. There was only skin holding it, so I got the hold of her arm and stuffed it into her skirt. As far as I could see she was dead.”

Mr Wilson, now 83, described performing CPR on the lifeless schoolgirl despite being quite disorientated.

“I was still quite deaf [from the blast] but I could hear people outside shouting ‘hand her out, hand her out. I didn’t hand her out until Gillian was conscious.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I always maintained that it was my job to look after the children and that’s what I did.

“Gillian was in hospital for months but I was only in for a short while but I was off work for a while with my nerves.”

Mr Wilson began his security force service as a member of the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC) in the late 1950s. He met his wife, May, in Lisnaskea on his first night on duty.

“She was coming from church and agreed to go on a date, so we went out the following night. We hit it off straight away,” he said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe couple were married for 60 years and were blessed with children Mervyn, Joy and James. Sadly, May passed away last November.

Mr Wilson had vivid memories of the challenges a young security force family faced living in a border area.

“I was transferred to Middletown, but my wife wouldn’t move as she looking after her father and mother. So I left the police at that point and went to Belfast and got a job driving the double-decker buses.

“I stayed there for a few years but got lonely and came home again.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I got a job driving the education buses and then I joined the part-time UDR. When I signed my name, they said ‘you’re a target from now on’.“

Mr Wilson knew all about the risk and he had a number of what he called “hairy nights” while serving with the USC along the Fermanagh border in the 1950s and 1960s.

“One night they blew the police station up that we were in. That was a bit of a hairy night because the bomb destroyed the front of Lisnaskea station but thankfully nobody was killed.”

On another occasion, a tree down across a country road turned out to be part of an elaborate bomb trap – foiled because the patrol was able to cut the tree and drive on rather than reversing away into a booby-trapped laneway.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We got away with one that day. The man above was looking after us,” he said with a wry smile.

Following the bomb attack in 1988, Ernie displayed a similar contempt for terrorism – driving the repaired bus around Lisnaskea in a show of defiance.

“The foreman came to see me when I was on the sick and asked me if I would like to collect the bus from Coleraine.

“So, I went to Coleraine and it was like a new bus. I couldn’t believe it,” he said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I drove it home, then I drove it up to the High School and drove it back down the town to the roundabout, and then back up again, and I did that three times before I took it back to the bus depot.”

Reflecting on the peace process made possible by the sacrifices of people like Ernie and his comrades, he said: “People today don’t appreciate the sacrifice.

“If they were expected to do what we were doing, they wouldn’t do it.”

• The name of James Wilson does not appear in the list of Troubles’ dead, but his father Ernie is adamant that the actions of the IRA resulted in his death.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJames had been taught to drive his father’s school bus on private land from a young age and took it upon himself to search the vehicle each morning before his dad commenced the school run.

That routine continued through the years and the morning of June 28, 1988 was no different. However, the police were also tasked to check the bus each morning but on this occasion the local RUC patrol was not available to attend.

Ernie was slightly delayed on his way to pick up the vehicle at Maguiresbridge school, leaving his son to drive it down to the school gates for collection.

The devoted father explains how the burden of failing to spot the device weighed heavily on his son’s mind, with tragic consequences.

He still struggles to talk about what happened to this day.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“After a while James began to get a wee bit funny about things, and out of the blue he asked me if I would go to Spain with him,” an emotional Mr Wilson said.

“I said we couldn’t go without his mother but he said, ‘no, just you and me.’

“So we went to Spain and we had a wonderful week, then we came home and he took his own life. My hair turned white overnight. Just overnight.”

Mr Wilson added: “I think James must have felt he let me down, which he didn’t, but he might not have known that.”