Roamer: Variations of Somme hero's kingly colloquialism continue 100 years on

“I was interested to read your piece on 29 June about the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh at Bushmills unveiling the statue of Robert Quigg VC,” Ross Chapman wrote from Newry.

He was referring to sculptor David Annand’s bronze monument depicting the local WWI-hero who rescued seven comrades from no-man’s-land while searching for an officer lost on the first day of the Somme, just over a century ago.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It reminded me of a visit to those parts in the 1960s,” Mr Chapman’s letter continued, adding “we used to have a week-long family summer holiday in Port Ballintrae.”

Ross, a vet in Coleraine in the mid-1950s, shared reminiscences of local acquaintances with their holiday hosts.

Memories of one, surnamed Quigg, prompted a conversation about Robert Quigg receiving his VC from George V. The Chapman family was told “when the King pinned the medal onto Robert’s jacket he said ‘You’re a brave man Quigg’ to which Robert responded ‘you’re a brave man yourself, Your Majesty!’”

Mr Chapman reckons that King George V “may have been taken aback by the compliment that he had received from the Ulsterman to whom ‘brave’ meant that he was decent, fine and noble.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe story that Ross and his family were told in Port Ballintrae in the 1960s is often repeated in the Bushmills area today.

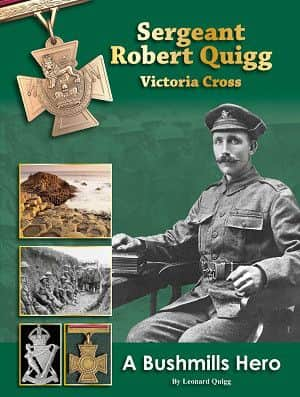

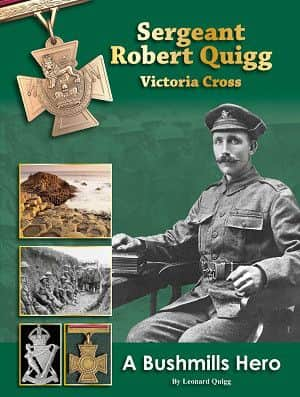

In a recently published book about the Bushmills hero, written by his great nephew Leonard Quigg, there’s a lengthy paragraph headlined “what Quigg said to the King!”

Here Leonard explains that his great uncle’s fame was “widespread” by September 1916 “because he was one of the few Great War soldiers who would survive to receive his high award in person.”

Sadly, the bulk of WWI’s VCs were awarded posthumously.

“During a Royal visit to France that month,” Leonard recounts, “Quigg was paraded before His Majesty King George V, much to the pride of his battalion and the 36th (Ulster) Division as a whole.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfterwards Robert’s Sergeant Major wrote a letter about the King’s visit.

“The King asked him where he came from,” the Sergeant Major reported, “he shook him by the hand, and said ‘You are a very brave man.’”

Leonard presumes that that this “gave rise to one of the most widely-known legends built around this quiet, modest man Quigg.”

Leonard’s book acknowledges “a variety of versions” of his great uncle’s response to the King’s pronouncement and offers his family’s considered interpretation!

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the North Antrim dialect “the word pronounced ‘brevv’” Leonard explains, is “a derivative of the word ‘brave’”

Robert’s great nephew admits that the word’s “meaning is rather vague but it is something like ‘quite good’. Thus, it can be used in a variety of expressions such as ‘it’s a brevv while since ah seen ye’ or ‘ah’m in brevv form so ah am!”

Leonard continues with his explanation - “when the King said to Quigg that he was ‘a very brave man’ Quigg is supposed to have wittily quipped ‘And yer a brevv wee man yerself, Sir!’

Buckingham Palace ‘brave’ and Bushmills ‘brevv’ are very different words!”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLeonard thinks that the account of the conversation, passed down in its various forms, is “a nice story, but hardly likely to be true, although the King would possibly have benefited from the assistance of an interpreter in his brief exchange of words with Quigg!”

Leonard’s book offers an endearing contextualisation of his great uncle’s tête-à-tête with King George V.

“Shy, country lad that he was, Quigg would have been overwhelmed by finding himself in the presence of Royalty and is likely to have been fairly tongue-tied on the occasion. He did have an impish sense of humour but he is most unlikely to have exercised it on the King.”

Leonard reckons that prior to the occasion Robert was “drilled and rehearsed in precisely what he should say.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd his Company Sergeant Major was undoubtedly near at hand, watching like a hawk!

To any divergence from the prescribed script,” adds Leonard, “would have resulted in a lengthy period of ‘fatigues’ in the battalion kitchen, or worse, latrine duty!”

Ross Chapman’s letter ended with another story from the Somme on 1 July 1916, “though very different, coming from the village of Bessbrook where a woman called Annie McCullough lived with her husband and family.”

Mrs McCullough was a practising Quaker “and as such saw a Divine quality in every human being, including German people. Her son Johnston, however, was drawn to military service and was keen to set off for the front.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“When the time arrived for him to leave the village, Annie had a last few words with her son. She prayed that he would not have to kill any Germans,” Ross’s letter continued.

“Johnston McCullough soon arrived in France and became part of the ‘big push’. Before there was any question of killing Germans he was an early causality. As he lay dying, he said to his brother-in-law who was serving with him ‘Tell my mother that I never killed any Germans.’”

Ross says that the message was brought back to Bessbrook “but we do not know if that was any consolation to Annie in her sorrow. Mothers carry such deep thoughts deep within.”