Autocratic and stubborn, but Kitchener's vision helped win Great War

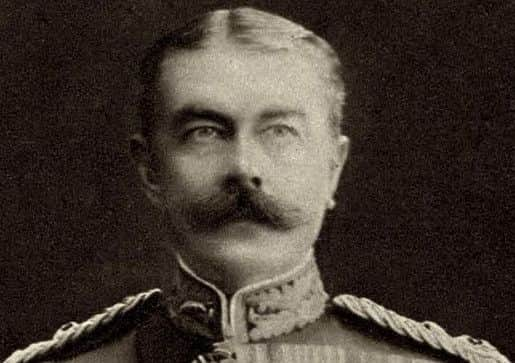

The iconic Field Marshal Lord Kitchener of Khartoum and Broome, the symbol of the British will to victory in the Great War, was drowned off the Orkney Islands on June 5 1916, when the cruiser HMS Hampshire, conveying him on a mission to Russia, was sunk by a German mine.

On the Western Front, as Lord Kitchener’s New Army of civilian volunteers, drawn from all walks of life, prepared for its great offensive on the Somme, a great wave of despondency afflicted many of the troops. As one soldier recalled: ‘We were in the front line, when all of a sudden a shout from the Jerry trenches told us that Kitchener was drowned and he would go to Hell’. Another said: ‘It was as bad as losing a battle’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdKitchener had called the New Army into existence but he did not live to see its first great engagement.

Kitchener, conqueror of the Sudan, commander-in- chief during the South African War and imperial administrator, was born on 24 June 1850, near Listowel, Co Kerry. Although born and bred in Ireland, he was not of Irish descent. Hence, Sir Edward Carson’s riposte to Kitchener’s complaint about attacks on him by Irish nationalists was rather apt: ‘Ah, but, as they say over there, to be born on a housetop does not make you a sparrow.’

However, it may also be noted that in 1910, when Kitchener visited his former family home, he astonished the Savages, his hosts and the then owners of the property, by remembering every field on the estate by its Irish name.

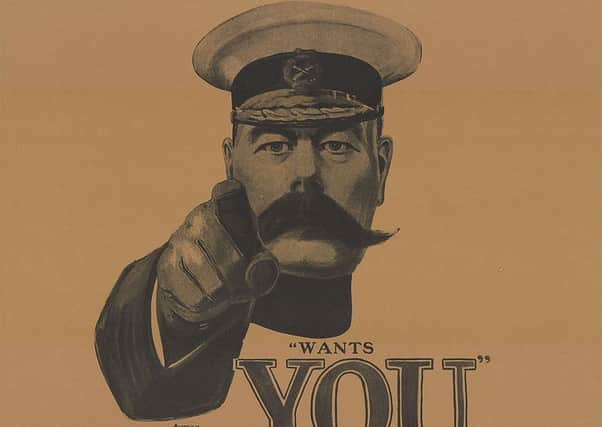

At the outset of the Great War H. H. Asquith, the Liberal Prime Minister, appointed Kitchener as Secretary of State for War. Margot Asquith, the Prime Minister’s second wife, acidly observed that he was completely useless as an executive head of the War Office but made a magnificent poster.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, Kitchener did possess one remarkable insight: the war would last a long time, contrary to the prevailing view that it would be over by Christmas, and to wage it a great New Army, of the order of 70 infantry divisions (‘a million bayonets’) would have to be raised.

As Kitchener failed to explain the thought processes by which he reached this conclusion, his Cabinet colleagues initially viewed his assertion with scepticism. Sir Edward Grey, the Foreign Secretary, assumed it was the product of ‘some flash of instinct rather than reasoning’ .

Kitchener had only reluctantly agreed to become Secretary of State for War, a point readily conceded by Asquith in his diary. Kitchener candidly admitted to Carson: ‘I don’t know Europe; I don’t know England; and I don’t know the British Army’. He had not been in England for most of the previous 40 years.

Many contemporaries would have discerned the hand of the Providence in the fact that he was in England when war broke out. Cynics would dismiss the fact as a fluke. He had seen service in the Sudan, Egypt, South Africa, India and Egypt again. He had been sirdar (commander-in-chief) of the Egyptian Army, commander-in-chief in India and proconsul of Egypt but his experience of the British Army at home was non-existent.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFurthermore, he was largely apolitical, distrusted politicians and his knowledge of the War Office and its operations was virtually negligible.

Kitchener is often criticised for not using the Territorial Army as the basis of expansion. Kitchener unfairly despised these ‘weekend’ soldiers. However, in Kitchener’s defence, it may be observed that the TA had been formed for home defence. Kitchener unjustly assumed that TA soldiers would be unwilling to serve abroad.

The overwhelming majority – 80 to 90 per cent of some TA units – willingly undertook foreign service. At Messines, during the First Battle of Ypres in October 1914, the TA soldiers of the London Scottish demonstrated that they could fight and die with courage and heroism to match any regular battalion.

Margot Asquith was correct when she described Kitchener the poster as magnificent. The impact of his iconic image and the slogan – ‘Your country needs you!’ – was stunning. For example on Tuesday August 19 1914 9,699 men enlisted. On Thursday September 3 1914 33,204 men joined up – almost the equivalent of one-third of the British army serving in France.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdKitchener’s extraordinary achievement was the creation of an army capable of meeting the demands of a continental war on an unprecedented scale. During the Great War a staggering 5.7 million men served in the British army, almost two million more than served in the Second World War. It is no exaggeration to say that the British Army of 1914-18 was ‘the most complex single organisation created by the British nation up to that time’. That distinction today probably belongs to the NHS.

Although the British public idolised Kitchener as the symbol of the national will to victory, his Cabinet colleagues found him exceedingly difficult. He was autocratic, stubborn and taciturn.

With justice Lloyd George compared his mind to a lighthouse which sent out a penetrating beam for a moment and then left utter darkness as the light revolved. Carson dismissed him as ‘that great stuffed oaf’. He was progressively stripped of responsibility for industrial mobilisation and strategy but he refused to leave the Cabinet. Some historians have alleged that ‘Kitchener was fortunate to die before his powers waned and his reputation was eclipsed by the tide of war’.

Other historians demur. Lloyd George’s acerbic summing up of Kitchener was ‘great driving force but no mental powers – that is my reading of him’.