Ben Lowry: We heard little yesterday in the reaction to Kenova about how hard it is to run an agent in a brutal terror group like the IRA

There is not so much a reaction yet to Jon Boutcher’s findings from senior former members of the security forces, although we report William Matchett’s response.

Senior former members of the security forces tend not to speak about their careers. Others who do have told this newspaper that they want to absorb the 208-page report before they talk.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the meantime, I want to zoom out and look at some of the more obvious underlying aspects to this story, and make a few points that I did not hear much made in those broadcasts I caught yesterday – although that might be partly because I was at the Stormont Hotel for much of the morning and early afternoon to view the report and attend a press conference (my questions to Mr Boutcher are printed on pages two and three).

The first, obvious, point is that running informers was a messy business. The Northern Ireland Troubles were at their peak more than 50 years ago, and much of the early security force response to the eruption of terrorism was flawed. That is one reason why more than half of killings by soldiers happened prior to 1975, in the first six years of a terrorist campaign that lasted the better part of 30 (the IRA from 1969 to 1997, with a two-year ceasefire from 1994 to 1996).

The military mostly realised that Bloody Sunday, for example, had been a disaster as soon as it happened, even if they (and the then government) stonewalled on inquiries at the time. There was no repetition of that tragedy, despite the fact that it helped usher in an even more violent phase of the conflict (the two worst months of the Troubles in terms of deaths were July and August of 1972, when Northern Ireland teetered on the brink of civil war).

Successive UK governments, after their initially confused response to the Troubles, sought to normalise Northern Ireland. My own generation, born at the the height of the violence (my school year was people born in late 1971, like me, or the first half of 1972) had a birds eye view of the normalisation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOur earliest memories are of what seemed to a child like the structure of a war zone (I have a snapshot memory of being in a car with my dad as he drove through an army checkpoint into the Royal Victoria Hospital in what I now think was early 1975), even though we have no memory of the most violent year, 1972. But we saw an ever improving Belfast – I remember events and shows in venues like the Ulster Hall at the end of the 1970s – and we all remember the opening of the Opera House in 1980, a key moment in the return of nightlife to the city. Restaurants such as Caper’s, the pizzeria, were bustling from as soon as they opened in the early 80s.

Central to that normalisation strategy was an understanding among the Tory and Labour governments and among security force leaders that they needed to be restrained if they were to avoid inflaming the situation.

That is a key reason why killings in Northern Ireland during the 1980s were markedly fewer in number (in most years under 100) than in the 70s (in most years over 200). During that latter decade, the increasing UK reliance on intelligence and agents has helping with normalisation.

There were high profile security force killings, that seem obviously to have been based on good information, such as by the SAS at Loughgall in 1987, Gibraltar in 1988 and Coagh in 1991.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

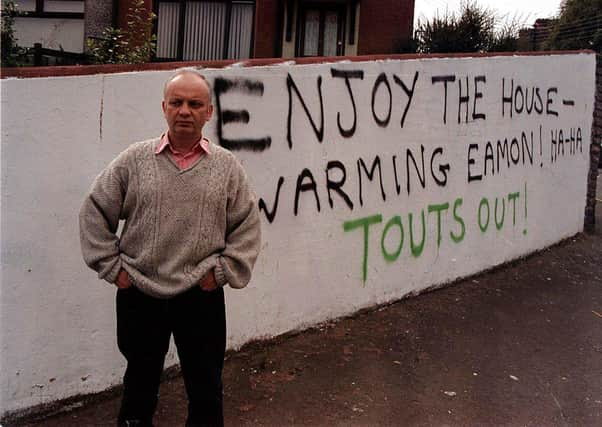

Hide AdBut another thing, I think, was clearly happening as the Troubles progressed. Some people who had become involved in terror became uneasy about their role. Partly perhaps it was age – an angry 17-year-old in 1969 might have become a mellower man of 30 in 1982. In at least some cases it was because they came to see that the society they were attacking was not as bad as they had once thought. Some men who turned on the IRA including Shane Paul O’Doherty, the late Sean O’Callaghan and the late Eamon Collins have all talked about moments when they realised the UK state was not as rotten as they had thought it was.

One of the many tragedies of the perilous business of running agents is that we will never know the motivations of some of those who turned on the IRA, because they were shot dead. And even if they had not been so killed, they might never have divulged their activities.

It is beyond horrifying to think of an IRA informant who knows that the person they are about to kill is also an informant but they can’t abort the killing without exposing their own double life.

Meanwhile, the IRA leaders were themselves, from the early 1980s, clearly looking for a way out of a campaign that was shown to have, at best, the support of around one in ten voters in Northern Ireland, a much smaller share of the population in the Republic.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI spoke to some senior members of the security forces yesterday and, while they are not yet ready to speak on the record, suffice to say for now that they view with contempt Mr Boutcher’s claims that the way Stakeknife was handled as an agent cost more lives than it saved. It is, they say, obvious that the success in the running of informers overall saved huge numbers of lives and indeed was a key reason why the IRA gave up its campaign in the 1990s.

I was struck by how little criticism there was of the whole concept of the Kenova investigation when it was launched in 2016. Instead of celebrating the success of the security forces in penetrating the most active terrorist movement in western Europe, we were (it seemed clear even then) assuming culpability on the part of their handlers. The questions at yesterday’s press conference showed that the media focus was on state failures.

We will report much more on this in the coming days. But at first sight, for all Mr Boutcher’s references to the difficult choices facing agent handlers, there seems to have been an elementary failure to understand the horrendous ethical dilemmas facing intelligence operatives in dealing with informants from a brutal terror group – dilemmas that are discussed in ethics classes by students at universities when still in the teens.