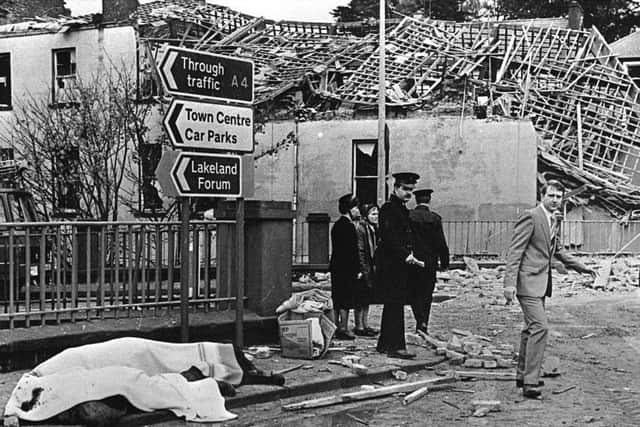

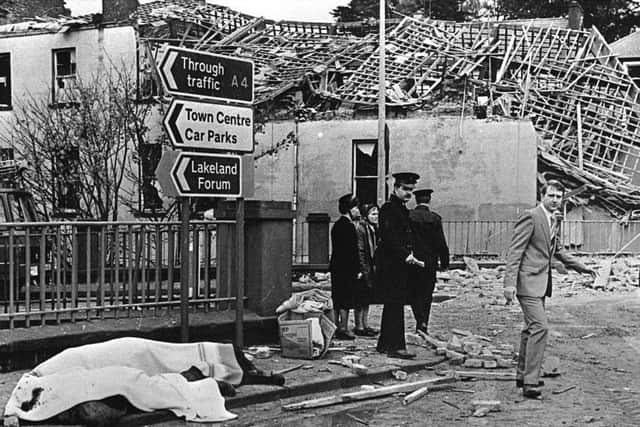

Lord Eames '“ As the dead and injured of Enniskillen were brought in, a nurse asked me: '˜Where is God in all of this?'

Standing at the door of St Macartin’s Cathedral in Enniskillen that morning of Remembrance Day, 1987 the conversation could not have been more normal.

I am uncertain who noticed it first. No sudden sound reached us up at the cathedral but across the roofs of the houses smoke had suddenly reached up into the sky.

A voice could be heard, “There’s been an explosion”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad‘The Poppy Day bomb’ had plunged Enniskillen into a nightmare and changed the lives of countless people forever.

Instead of the normal pattern of Remembrance Day worship we found ourselves in the corridors and wards of the Erne Hospital among a shocked and bewildered community.

There was the frantic searching for loved ones missing after the explosion, the trollies containing the wounded and the dying, the hurried conversations and speculation, the staff rushing in from their Sunday off-duty at home as word spread of the emergency and the relatives arriving with their anxious questions.

For hours, clergy of all denominations moved from group to group; payers were offered, hands held, words of comfort spoken as the enormity of it all began to dawn.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMy recollections of that day remain vivid. No course in pastoral theology could possibly have prepared a person for the demands presented by those hours in the hospital.

Listening to the questions about those who had been standing beside them at the cenotaph, trying to relate members of the same family separated in corridors or wards, accompanying hospital staff when they requested support in breaking the news of a fatality to a loved one and simply being there in the midst of it all praying for strength to be somehow adequate to the demands whatever they might turn out to be.

In all honesty, the urgency of that day removed any lofty presumptions of theology to what we were doing. Few tried to reason out the doctrinal or theological approaches to such crying human need.

You reacted to requests or you did what you thought appropriate: thinking about it would come later ... much later.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo, it was something of a reality shock when it happened. At the end of a corridor a table had been set up to provide tea manned by local volunteers.

She had been one of the first off-duty nurses to arrive at the hospital when local radio had appealed for urgent assistance: “Archbishop, where is God in all of this?” she asked me.

Spoken in the chaos of that morning by a nurse called upon to support and care for those in desperate need, but also from the lips of thousands across the years was the same question.

From the devastated and agonised lips of parents or husbands and wives at their parting from a loved one taken from them by faceless and unknown men. From the lips of those scarred for life by an explosion when they were in the wrong place at the wrong time. From the mouths of ordinary decent men and women who struggled to make sense of what was happening day and night.

Where, then, was God in all of this?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor the Christian, the daily efforts to relate his or her faith to the realities of life will depend on many ingredients. Each will have a personal aspect and interpretation of their understanding of the faith.

For me in my own pilgrimage with all its continuing questions and degrees of revealed truth, I have turned to the biblical accounts of Holy Week and the Resurrection.

Above all other passages of scripture, the final weeks of Christ’s earthly ministry and especially the events at Calvary have given most relevance to my experience. This I have found in personal reflection and periods of spiritual heart-searching.

With my memories of ministry during the Troubles it was the Passion, suffering and resurrection of Christ which spoke most clearly to me as an individual. When faced with tragic situations it was there I found most understanding of ‘the God in all this’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTo be truthful, each time I have reflected on the Passion I have found more and more to prompt my thinking on the nature of suffering, the meaning of injustice and the fragmentation of com- munity life.

One of the dangers of Christian ministry lies in having a neat and seemingly certain explanation for every eventuality of daily life. I have often envied those who have an explanation of the meaning of every emotion and experience when related to the Gospel.

There will be and often are occurrences in life where our conscience and understanding lead us directly to an answer. but there are those times when we will “see through a glass darkly” as St Paul puts it when there is no clear response.

Time and again I have been confronted by such questions in my ministry. in that respect, I am no different to any priest or minister. People react to situations in a personal way and no two cases are the same. emotions such as anger and resentment, disbelief and frustration, sadness and a sense of devastation are but only some of them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Troubles produced such reactions in abundance. ‘Why, why, why’ were on many lips. no matter the strength or weakness of personal faith and belief the questions came fast and furious.

Often the most testing of circumstances in the Troubles came when a microphone was thrust in your face and a camera lens focused on your expression. “What is your reaction to this, archbishop?”

Hard though it was to think on your feet and without much preparation the need was to provide an alternative to the comments of anger or calls for revenge. Somehow the words of moderation, comfort and above all Christian input had to be found.

The grieving nurse all those years ago in Enniskillen asked the searching question. There were no easy answers. Theological debate could wait till later.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe immediacy of the Troubles called for a suffering Church alongside a suffering community, but also a Church prepared to point the way forward towards hope.

This is where the real answers to her question must begin. Sharing in the suffering of Calvary helped the believer to sense something of the glory of Easter Day.

Sharing in the suffering of all those ‘Enniskillens’ called the Church to point towards a resurrection in ways that could make an ultimate sense of it all.

Perhaps the theologian more than anyone can read a significance into the timing of the agreement which marked the turning point for the post-conflict society. The Good Friday Agreement of 1998 finally turned a corner in the infant peace process.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs Christians reflected on the cross of Calvary, all the efforts to reach a political blueprint for stability took the most tangible step forward.

For the churches, there was the sense of prayers being answered, few within faith communities questioned that spiritual reality. Out of a contemporary crucifixion experience society began to breathe again the air of hope.

My mind went back to the nurse. Her question was, even at the Good Friday Agreement announcement, difficult to answer.

Throughout history, conflict situations raise innumerable moral questions. The distinction between right and wrong becomes utterly subservient to personal persuasion.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPhilosophers will continue to draw conclusions and academics will long ponder but the actual experience of living through such times raises other more urgent issues. On what grounds did the Christian voice condemn violence in the Troubles?

Were we consistent in what we said? could we have done more to influence events?

For myself, such questions will continue to confront my remembering.

There is always that spiritual consolation that the ultimate judgement lies not in human hands – not even for the Church.

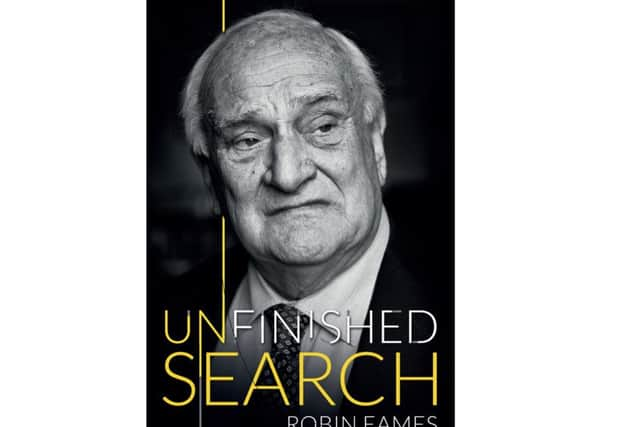

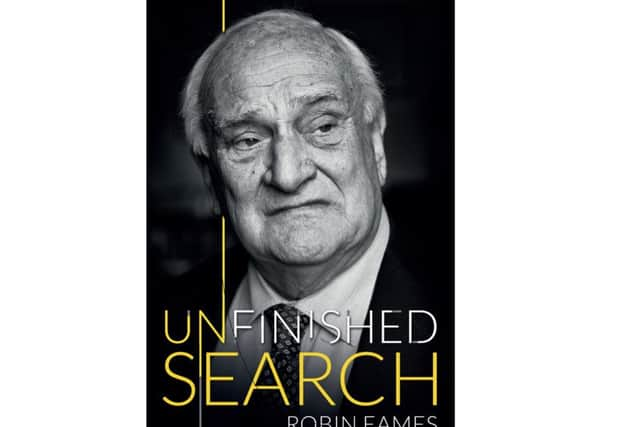

• Lord Eames is a former Archbishop of Armagh. This is an abridged extract from his book ‘Unfinished Search,’ which was published on Thursday by Columba Press, priced £17.99.