Coronavirus emergency may kill off ‘Boris Bridge’ – but it also shows United Ireland is highly hazardous

This mitigated the suffering which mass unemployment and wholesales business collapse might otherwise have produced, but it is not without consequences. There’ll be long-term challenges as UK government debt once again rises above 100% of GDP.

There are aspects particular to Northern Ireland. NI has long been in a position – since at least the late 1960s – where government spending in the region far exceeds the tax revenue raised here.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy implication, we have received a large fiscal transfer from the UK Exchequer. In 2018-19 that transfer was £9.4bn, equivalent in scale to about one-fifth of NI’s GDP.

On 14 April, 2020 the official and independent UK budget watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), projected that the response to Covid-19 was likely to involve a massive increase in UK public spending alongside a huge decrease in tax receipts. These combined effects would raise the UK government’s deficit by over £200bn (tax revenues falling by £130bn and spending increasing by £85.5bn).

We can assume that NI would experience an at least proportional increase in subsidy, and decrease in tax receipts.

Alongside this it is worth noting that even when the lockdown is over, the longer-term (scarring) effects of the shut-down are likely to produce large extra demands for public expenditure. Even before March 2020 the NI public expenditure situation was grim. Devolution had been restored in January but the accompanying financial package from the Treasury (up to £2bn, although some of that money had previously been indicated through the confidence-and-supply agreement) fell short of estimates of the various ‘unfunded spending pressures’ which may have amounted to well in excess of £5bn.

Covid-19 implies further unfunded pressures, such as:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Adl Translink’s operating deficit has increased (it may need an injection of about £100m)

l Revenues of the two universities were badly hit (in some scenarios by up to £140m)

lConstraint on more “routine” hospital activity may imply that, once lockdown is over, hospital waiting lists are longer than they were before – hence raising an

already very large spending requirement needed to clear them

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Adl Markets for agriculture products have been badly disrupted – will some sort of emergency support be required?

But there are questions, ultimately partly political, about how we might respond to h a situation where NI’s fiscal dependence on the UK Treasury has grown tremendously.

As optimistic view would regard the fiscal transfer as the ultimate safety net. A safety net which worked in a time of national crisis.

A more cautious view would note how in the past (RHI is an example but far from the only one) a reliance on “free money” coming from London has distorted behaviour in ways which are not helpful: it has become an example of moral hazard, because we assuming the subsidy is always there we do not make the hard decisions about improving policy and performance in NI.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 2019 two professors of Economics in Dublin, John FitzGerald and Edgar Morgenroth, argued that the great scale of the financial transfer from GB to NI made a united Ireland a hazardous prospect for both NI and the Republic of Ireland in any medium term period.

The fiscal implications of Covid reinforces their conclusion: the fiscal transfer has grown a lot, and the 26 Counties are now themselves much more indebted than they were previously.

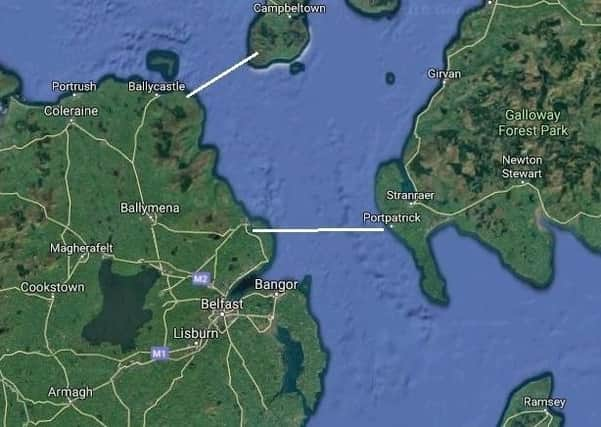

But at the same time the ballooning fiscal deficit makes it much less likely that any UK government will subsidise grand projects relating to NI – that includes the so-called Boris Bridge from NI to Scotland.

Dr Esmond Birnie

Senior Economist, Ulster University Business School (and ex-UUP MLA)

A message from the Editor:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

With the coronavirus lockdown having a major impact on many of our advertisers - and consequently the revenue we receive - we are more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription.

Subscribe to newsletter.co.uk and enjoy unlimited access to the best Northern Ireland and UK news and information online and on our app. With a digital subscription, you can read more than 5 articles, see fewer ads, enjoy faster load times, and get access to exclusive newsletters and content. Visit https://www.newsletter.co.uk/subscriptions now to sign up.

Our journalism costs money and we rely on advertising, print and digital revenues to help to support them. By supporting us, we are able to support you in providing trusted, fact-checked content for this website.

Alistair Bushe

Editor