Is Mycoplasma bovis affecting calf health on your farm?

Exposure to Mycoplasma bovis increases the risk of calves being treated for respiratory disease, and Mycoplasma bovis is not uncommonly isolated from the lungs of pneumonic calves so it’s important when controlling youngstock respiratory disease that we understand the role of Mycoplasma bovis.

How is it spread?

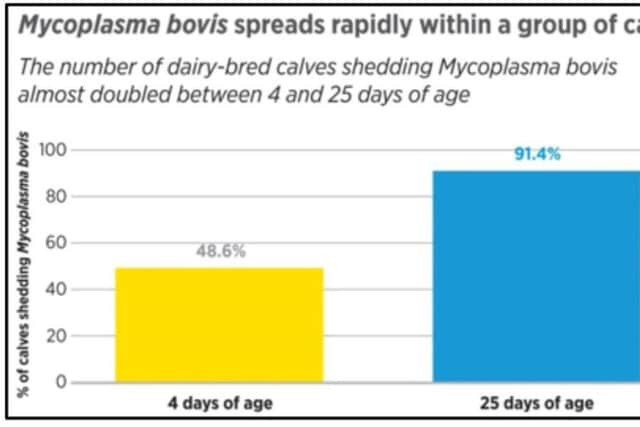

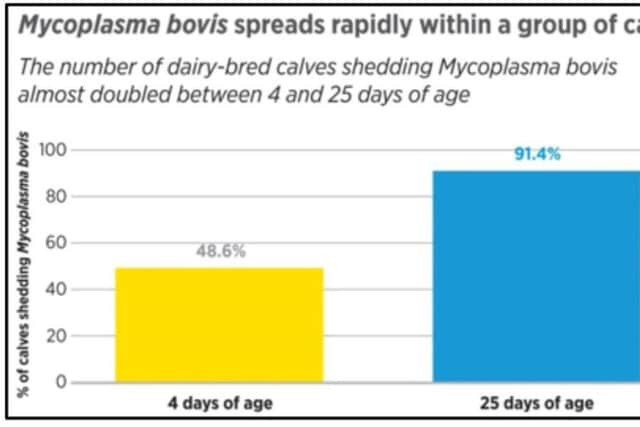

The main sources of infection are respiratory secretions and infected milk. In infected herds, calves become infected when they are very young, either in the calving pen, from ingesting infected colostrum or milk, or from close contact with individuals shedding Mycoplasma bovis in respiratory secretions. Calves then go on to shed Mycoplasma bovis in large numbers particularly during the first two months of life, playing an important role in onward spread of infection. In one study the proportion of calves shedding Mycoplasma bovis increased from 49% to 91% of the group in just three weeks. Where calves are sourced from multiple farms its clear to see that getting on top of Mycoplasma can be challenging.

What are the clinical signs?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdClinically signs are typical of calves with respiratory disease; elevated temperature, increased respiratory rate, breathlessness, decreased appetite with or without nasal discharge and coughing.

Affected calves may also suffer from middle ear infections, arthritis, or both. Middle ear infections can occur as single cases or as outbreaks. Calves are seen with drooping ears, a head tilt and balance problems. Some will also have problems swallowing and others may go on to develop meningitis.

How Common is it?

Prevalence varies across regions and between production systems, but it’s well established that across Europe, Mycoplasma bovis is a highly prevalent bacteria.

Exposure increases in systems which rely on mixing of animals from multiple sources, and with high stress husbandry systems. A study on Belgian veal units found Mycoplasma bovis in 87.5% of respiratory disease outbreaks.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn an Italian study, 100% of the six month old veal calves at slaughter had been exposed to Mycoplasma bovis. ‘In the UK’ 2015 data from a subsidised serology scheme run by Zoetis showed 50% of ‘2460 calves’ with a history of respiratory disease, had been exposed to Mycoplasma bovis. This figure had increased from 45% in 2014 and 41% in 2013. In Northern Ireland 59 out of 77 farms investigated by Zoetis in the course of 2015-2016 showed evidence of exposure to Mycoplasma bovis and on average 64% of calves (238 out of 372) had positive titres.

How do we control it?

There are currently no commercially available vaccines for protection against Mycoplasma bovis, so control needs to focus on minimising the exposure of naive animals. The main sources of Mycoplasma bovis are contaminated milk and respiratory secretions from infected (but not necessarily clinically affected) animals.

Four areas to consider;

1. Minimising the risk of spread from dam to newborn calf:

Removing newborn dairy calves from the cow and calving box as soon as possible after birth reduces the time, and therefore the risk, of spread of infection.

2. Minimising the risk from contaminated milk:

This is achieved relatively simply by feeding artificial milk replacer, but of course it’s essential that calves receive adequate colostrum as soon as possible after birth, and Mycoplasma bovis can be passed in the colostrum as well. Risk can be minimised by screening cows and then if necessary careful selection of cows eligible to contribute to a colostrum pool (bearing in mind other disease risks such as Johnes). Pasteurisation of colostrum on a low-temperature, long-duration setting (60˚C for 60 mins) minimises the risk of transmission of infection without destroying the vital antibodies.

3. Minimising risk from purchased cattle:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIdeally, screening, quarantine and, if applicable, a treatment policy could be used to minimise the risk from incoming animals. Less effective but a more viable option on many units will involve separating animals on arrival when they are stressed and likely to be shedding more Mycoplasma bovis.

4. Minimising the risk of animal-to-animal spread:

Mycoplasma bovis will spread from animal to animal primarily in respiratory secretions, so sick calves with increased shedding should be separated. Ensuring excellent air circulation will reduce the bacterial load in cattle buildings. Mycoplasma bovis is susceptible to common on-farm disinfectants. So, all-in, all-out policies for cattle sheds, coupled with effective disinfection of the housing between batches, is a practical solution for many.

In Conclusion

Mycoplasma bovis alone or in combination with other respiratory pathogens, can cause significant disease. Control relies on improving overall calf health, minimising the exposure of naive cattle and when required implementing effective treatment regimes.

Appropriate vaccination and control programs should be in place for the respiratory viruses such as BRSv, PI3v, IBR and BVDv, since controlling other pathogens will help decrease the risk of Mycoplasma bovis co-infections.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUntil alternative options (such as vaccines) for Mycoplasma bovis control are commercially available to protect against infections, antibiotics remain the only available treatment option. Where Mycoplasma bovis infection is suspected or confirmed, prudent and targeted use of antibiotics that are effective against this pathogen is required.