The 1947 Education Act was Stormont’s most significant legislation up until 1972

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the 1947 Education Act, the local equivalent of R A Butler’s 1944 Education Act in England and the 1945 act in Scotland.

The 1947 act probably ought to be regarded as the most significant legislation to have been passed by the Northern Ireland Parliament between 1921 and 1972.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

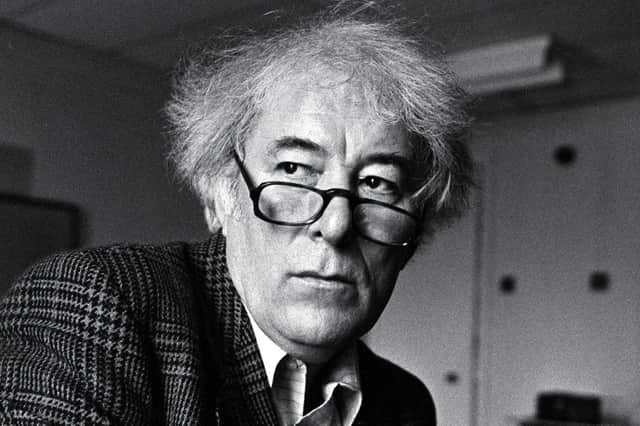

Hide AdIn an interview in the New York Times in December 1979 Seamus Heaney acknowledged its importance to his generation. John Hume, David Trimble and a great many others, if asked, would have said the same. Professor John Wilson Foster has written effusively about the opportunities the act afforded him.

The act was far-sighted and far-reaching in its scope.

For the first time, all children over 11 would receive free secondary education.

The act introduced the 11+ examination enabling 25% of pupils to attend grammar schools.

The school leaving age was raised to 15.

The provision of free school meals, milk, transport, textbooks and medical examinations was either introduced or extended.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGrants were introduced for those progressing to third-level education.

The quality of teacher training was to be improved.

The funding of the Roman Catholic voluntary sector was increased from 50% to 65%, which was more generous than in England but fell short of the 100% the Roman Catholic Church hierarchy sought.

The act put Northern Ireland two decades ahead of our southern neighbours. In September 1967 Donogh O’Malley, the Fianna Fail education minister, announced his broadly similar package to journalists and on a Saturday (during a month when the Dáil was in recess) without consulting ministerial colleagues.

O’Malley’s Machiavellian calculation was that his proposals would be so popular with the public, that it would be impossible for ministerial colleagues worried by the cost implications to go back on his word.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEducational reform is often fraught with difficulty as is evidenced by A J Balfour’s Education Act of 1902 or Lord Londonderry’s legislation in 1923. The main provisions of the Butler Act were drafted by senior civil servants based on ideas, many of which had been around for a long time. Butler’s decisive contribution was to create a consensus to secure the bill’s passage by negotiating with a wide range of interested parties.

Although essentially replicating Butler’s legislation, as Professor Graham Walker pointed out in a piece to mark the 70th anniversary of the Northern Ireland legislation, consensus building here was not easy: ‘The act was not pushed through without difficulty or controversy. There was fierce Orange Order and populist Protestant opposition to the act’s provisions to increase funding to the Catholic school sector (notwithstanding the Catholic Church’s refusal to allow state representation on the governing boards of their schools), and the act’s outlawing of bible-teaching in the non-denominational schools which were in practice attended almost exclusively by Protestants.’

R A Butler is closely identified with the English legislation and was described in his obituary in The Times in 1982 as ‘the creator of the modern educational system’. By contrast, Samuel Hall Thompson who was responsible for the Northern Ireland legislation is an almost wholly forgotten figure who deserves better from posterity.

Butler enjoyed an exceptionally long ministerial career (from 1931 to 1964 apart from the period 1945-51 in opposition when he laid the solid foundations of the post-war Conservative revival) and he was one of only two British politicians in the 20th century to have served in three of the four ‘great offices of state’ without becoming prime minister, a role for which he was passed over twice: in 1957 and 1963.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA donnish figure, Butler possessed a high-powered intellect but not the necessary killer instinct to become prime minister. As Enoch Powell pithily explained: ‘We handed him the loaded revolver but he declined to pull the trigger.’

After retiring from politics in 1965, he was appointed master of Trinity College, Cambridge, a role he fulfilled to perfection.

Samuel Hall Thompson was born into an Ulster-Scots family and was the son of Robert Thompson, the Unionist MP for North Belfast between January 1910 and 1918.

Like his father, his background was in the linen industry. Both father and son were chairmen of Lindsay, Thompson & Co, Flax spinners.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSamuel was elected to Belfast corporation in 1922 and became an alderman for the Clifton ward. He served as chairman of the electricity committee and the education building committee.

In 1929 he was returned unopposed as Unionist MP for Clifton. He served on the public accounts committee, was acting deputy speaker, and was vice-chairman of the Stevenson health committee. In 1943 he became chairman of the standing committee of the Ulster Unionist Council.

Having military experience both prior to the Great War and during it, in 1939, he rejoined the Army and was appointed chief ordnance officer for Northern Ireland with the rank of lieutenant-colonel, a position he retained until 1942.

Compared to Butler, he had a brief ministerial career, only being minister of education between 1944 and 1950. As Professor Walker’s observations suggest, Hall-Thompson had a more challenging task than Butler in piloting his legislation through the Northern Ireland House of Commons.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe resigned in 1950 because of opposition to his plans to pay the national insurance and superannuation contributions of Roman Catholic teachers.

In the general election of 1953 he was narrowly defeated by Norman Porter, an independent unionist and a bitter critic of Hall-Thompson’s reforms. Porter could perhaps be regarded as a mentor to a youthful Ian Paisley who accused Hall-Thompson of subsidising ‘Romanism’.

Unusually for a Unionist MP, Hall-Thompson was not an Orangeman but he was active in other spheres. He was chairman of the board of governors of Campbell College (as was his father), master of the North Down Harriers, and president of the Irish Bowling Association. He died at his home in Belmont on October 26 1954.

Hall-Thompson’s life is commemorated by a stained-glass window in Belmont Presbyterian Church.

As a supporter of Captain Terence O’Neill, Lloyd Hall-Thompson won his father’s old seat in the ‘Ulster at the crossroads’ general election of 1969.