April Fools Day 1873 prank was revealed in historic sea tragedy

Except the bridge wasn’t announced on April Fools’ Day!

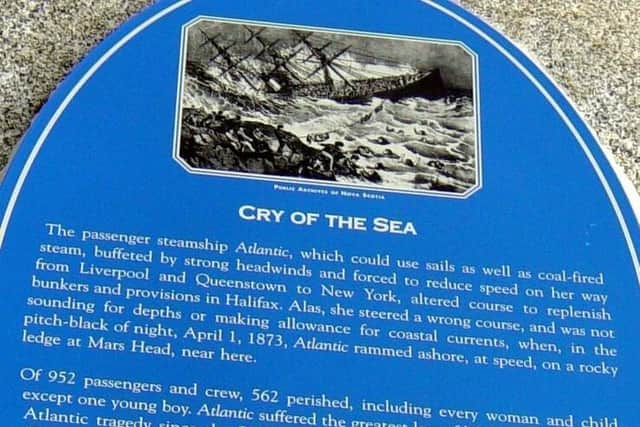

While both concepts share unequal elements of reality and hilarity, an announcement on April 1 almost 150 years ago added tragedy to the equation.

Amidst sad news of a maritime disaster came the story of a burly young sailor whose hugely convincing prank was found out on April Fools’ Day in April 1873.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe remarkable story (which had links with Northern Ireland) came to light in a weekly American magazine on April 19 1873.

Part of the story was about a young sailor called Billy, recalled by his sea-going friends as a lad who liked drinking with his mates “and was always begging or stealing tobacco”!

In his early 20s he was “the heart and soul of the crew”, described in the magazine as “a great favourite with all his workmates.”

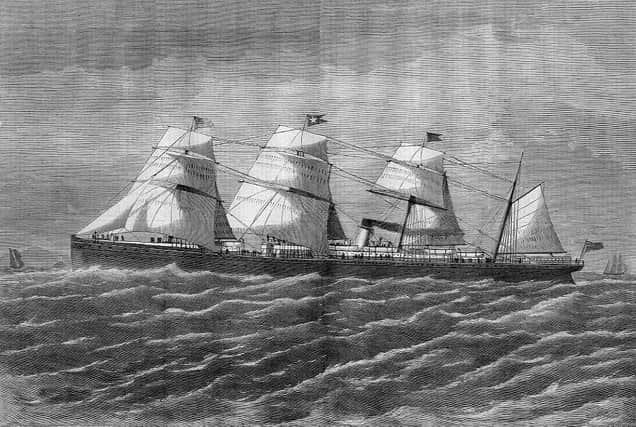

Billy worked on the 3,700-ton Belfast-built SS Atlantic, a Harland and Wolff passenger ship launched on the Lagan on November 26 1870. With tattooed arms and coarse sailor’s clothes like his mates, Billy loved the sea, the rough and tumble, the hard slog and supping grog back in port with his crewmates. And he’d sailed three long voyages on SS Atlantic before they discovered he was a girl!

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis ruse was revealed on April Fool’s Day in 1873 but the revelation was completely overshadowed by the Belfast vessel’s tragic demise.

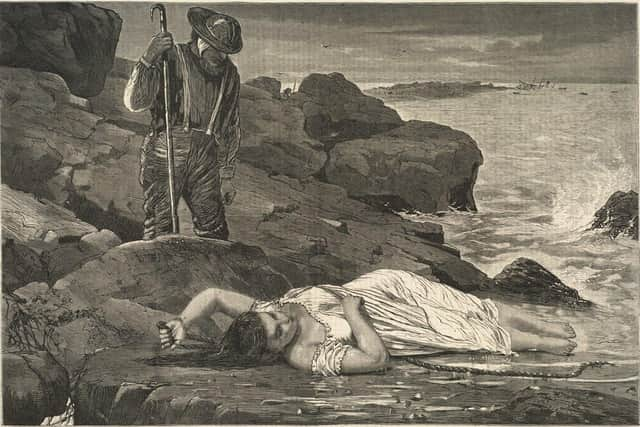

It was the North Atlantic’s worst shipping disaster until Titanic, over 40 years later. Billy’s clothes were torn from her body when SS Atlantic, sailing to Halifax with almost 1,000 passengers and crew on board, hit rocks in a fierce storm off Nova Scotia.

When Billy washed ashore along with nearly 600 lifeless bodies her secret was divulged.

Captain James A. Williams was in charge of SS Atlantic at 3.15am when it smashed into rocks and foundered.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAccording to Nova Scotia museum’s account, the stricken vessel “took 562 lives with it, including all the women and children, with the exception of one young boy. Had it not been for the heroism and bravery of the seaside community, that number would have surely been much larger.”

Maritime Historian Robin Gardiner outlines the first moments of the tragedy - “In seconds, five great holes were torn in her iron plating.”

Hundreds of passengers perished in their bunks, wakened by the “noise and shock of the ship grinding onto the rocks” and immediately succumbing to “torrents of freezing water” deluging into their cabins.

“Water poured into the hull through every opening,” Gardiner recounts “the survivors were obliged to climb the rigging to escape the raging seas. Then, with a huge roar the boilers exploded.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMost of the listing vessel’s lifeboats were torn from the decks, and few of those that remained could be launched in the high, freezing waves.

Survivors clinging to the masts quickly died of hypothermia. Many were swept away amongst splintered lifeboats and jagged wreckage. Local fishermen were alerted, and led by the Reverend William Ancient, the parish’s Anglican clergyman, they used their tiny boats to rescue survivors clinging to the rocks or clutching onto the rigging of the crippled ship.

Locals struggled to care for those that managed to make it to the shore and there were many feats of heroism amongst SS Atlantic’s crew.

A sailor in the rigging kept a woman-survivor from falling into the raging waves for six hours until the Rev. William Ancient succeeded in throwing him a rope and getting them both off. The clergyman later described the devastation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“By afternoon all the remaining living had been rescued or washed off except a boy, and a man and a woman still tied in the rigging on the mizzenmast high out of the water.”

The man was J. W. Firth, SS Atlantic’s First Officer, who’d fastened the woman to the mast and promised to remain with her until they were rescued.

A young Englishman succeeded in reaching the deck with his wife and child and helping them into the mizzen rigging, but a wave snatched the child away. Against all the odds Quartermaster John Speakman secured a rope to a rock.

Together with Third Officer Cornelius Brady they hauled a heavier line from the ship to the rock.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdApproximately 250 men used this tenuous link, plus three other ropes, to make the 40-yard struggle from the vessel to the rock.

Later Speakman swam from the rock to a nearby island with another rope.

There was now a link from the vessel to the shore but most survivors were too exhausted to attempt the treacherous journey.

An old photograph shows a burial service of some of SS Atlantic’s dead, with the Rev. Ancient reading the service beside the still-open grave, lined with coffins.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdProtestants were buried in a little cemetery at Terence Bay and Roman Catholics were interred nearby. There are several poignant memorials in the area marking an April Fools’ Day overshadowed by tragedy. No one knows who Billy was, except that he was a girl.