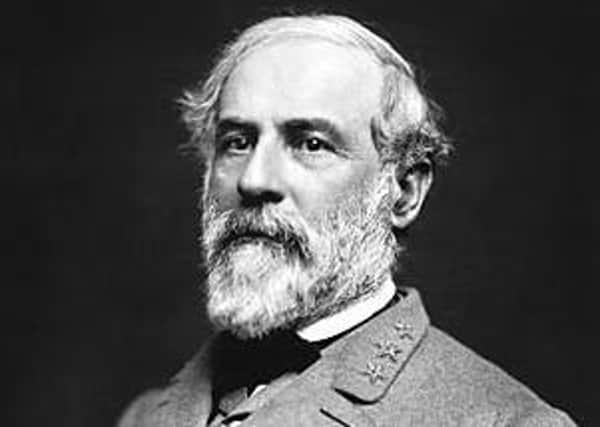

Icon of the Civil War, but just how great a general was Robert E Lee?

In April 1861 Lee declined command of the entire Northern army, resigned from the army in which he had served for 36 years and followed Virginia out of the Union. Although opposed to secession, he said: ‘I cannot draw my sword against my native state.’

Although Lee described slavery as an ‘amoral and political evil’ in 1856, claims that he never owned a slave himself and that he freed those that had belonged to his father-in-law are now widely dismissed as popular mythology.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDespite lack of manpower and material, Lee’s military genius was the principal factor in keeping the Confederacy alive. He was a legend in his own lifetime. In May 1862 ‘Stonewall’ Jackson wrote: ‘Lee is the only man I know whom I would follow blindfold.’ His soldiers, to whom he was either ‘Uncle Robert’ or ‘Marse Robert’, idolised him.

In his classic memoir ‘Co Aytch’ (‘Company H’) Sam Watkins, who served in the Confederacy’s First Tennessee Infantry and saw action in battles from Siloh to Nashville, thought Lee ‘looked like some good boy’s grandpa. I felt like going up to him and saying good evening Uncle Bob! … His whole make-up of form and person, looks and manner had a kind and soothing magnetism about it that drew everyone to him and made them love, respect and honor him. I fell in love with the old gentleman and felt like going home with him’.

Yet mild-mannered Lee was an audacious and ferociously aggressive military commander.

When Lee took command in Virginia, George B McClellan seriously misjudged his opponent by observing that Lee ‘is too cautious and weak under grave responsibility – personally brave and energetic to a fault, he is wanting in moral firmness when pressed by heavy responsibility and is likely to be timid and irresolute in action’. If McClellan had possessed greater critical self-awareness he would have realised he was describing himself.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough strategically a Union victory (because McClellan halted Lee’s advance into Maryland), Antietam was a tactical Confederate victory because the ‘timid’ Lee had fought an army almost twice the size of his own to a standstill by moving his army across the battlefield to repulse three Union thrusts launched separately and sequentially against the Confederate left, centre and right.

The Battle of Chancellorsville represents Lee’s aggression at its most stunning. Although outnumbered two to one, he achieved victory, through dividing his army and encircling the enemy in one of the most audacious moves in military history.

Pickett’s charge on the Union lines on Cemetery Ridge on the third day of Gettysburg represents Lee’s greatest miscalculation. James Longstreet warned Lee: ‘I have been in pretty much all kind of skirmishes, from those of two to three soldiers to those of an army corps, and I think I can safely say there was never a body of 15,000 men who could make that attack successfully.’ Lee’s blood was up and he thought audacity and courage would suffice.

Although Longstreet’s advice was disregarded, his appreciation of the impact of modern firepower proved correct. Less than half of the cream of the Army of North Virginia made it back to their own lines. Lee rode out to meet them: ‘It was all my fault; get together and let us do the best we can toward saving that which is left us.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter Gettysburg (and the capture of Vicksburg on the Mississippi), the strategic initiative passed permanently to the North and the defeat of the South was inevitable, subject only to the important proviso the Union’s will to fight held firm.

President Lincoln brought U S Grant east from his triumphs at Vicksburg and Chattanooga to confront Lee. Grant was stunned by the ferocity of Lee’s resistance but, unlike his predecessors, Grant refused to back off, waging a bloody war of attrition (including the Battles of Spotsylvania and Cold Harbor) which lasted exactly a year.

After Lee’s defensive lines broke under the weight of massive Union assaults in the spring of 1865 Lee could no longer defend Richmond, the Confederate capital. He embarked upon a week-long retreat. Incapable of going any further, his men fell out through hunger and exhaustion, animals collapsed and units disintegrated.

At Appomattox Court House on April 9 1865, Lee found himself almost surrounded and massively outnumbered. He told one of his aides: ‘There is nothing left for me to do but go and see General Grant and I would rather die a thousand deaths.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGrant’s considerate behaviour, at least partially in deference to Lincoln’s wishes, made the ordeal of surrender less painful for him.

Remarkably throughout the war it would seem that Lee never referred to his Union opponents as ‘the enemy’ but as ‘those people’. On this reading of the past, this extraordinary absence of bitterness and the man’s own innate dignity enabled Lee to accept defeat and seek to ‘bind up the wounds’ caused by the war by preaching to his people the necessity of peace and national unity.

This perspective is repudiated by those who insist that Lee was not conciliatory towards the North, that he championed southern grievances and that he was antagonistic towards the emancipated slaves.

Finally, if Lee was such a genius, why did the South lose? Explanations rarely focus on Lee’s inability to deliver victory but tend to major on the North’s demographic and economic advantages. Yet history provides examples of weaker powers defeating stronger ones. Lee’s greatest failure surely was that he never produced a war-winning strategy. He was curiously blind to the crucial importance of the Western theatre. Impressive though his victories were, they were achieved with ‘Stonewall’ Jackson at his side. After Jackson’s death (from ‘friendly fire’ at Chancellorsville) there were no more victories. Apart from Grant, most of his Union opponents were fairly mediocre.

Is it too harsh to suggest that Lee’s iconic status owes more to the psychological needs of the post-war South than to his military genius?