Notes from The Roamer’s mailbox during the coronavirus lockdown

I’ve been reminded of the 1957 flu pandemic that swept the world, bringing three times as many fatalities to Northern Ireland than the previous year’s local epidemic. I was seven years old when it stuck, and until now I’d forgotten that most folk in our street were affected and our whole family was bedridden for nearly a week. And I’ve been pondering with regular-reader Stephen from Antrim if the current era of Covid-19 hasn’t so much ‘unfolded as unleashed’!

We were mulling over the sudden disappearance of cash and those once-ubiquitous handfuls of coins and wads of pounds-sterling that seem to have vanished overnight from our wallets, pockets, handbags and purses.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I haven’t seen any real money since last month,” I told him.

“I haven’t seen any real money since I got married!” quipped Stephen.

(Please send your notes, quotes and anecdotes about the lockdown to Roamer’s mailbox address at the bottom of the page.)

Amongst some other readers’ e-mails responding to recent topics was a reference to Norwegian artist Edvard Munch, famous for his macabre portrait of a screaming man.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOften reproduced on Halloween face-masks it’s said to be the second most famous painting in history, after Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa.

Munch was mentioned here last month because one of his lesser-known paintings, a self-portrait, was painted during the so-called Spanish Flu pandemic that followed WWI in 1918-19.

The painting is considered to be one of the few works of art depicting the global pestilence that caused considerably more casualties than the Great War itself.

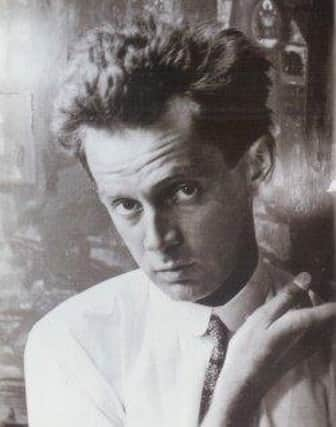

But Bangor-artist Leslie Nicholl tells me that another internationally renowned artist is also remembered for his work during the 1918-19 pandemic. He was the famous Austrian painter Egon Schiele.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

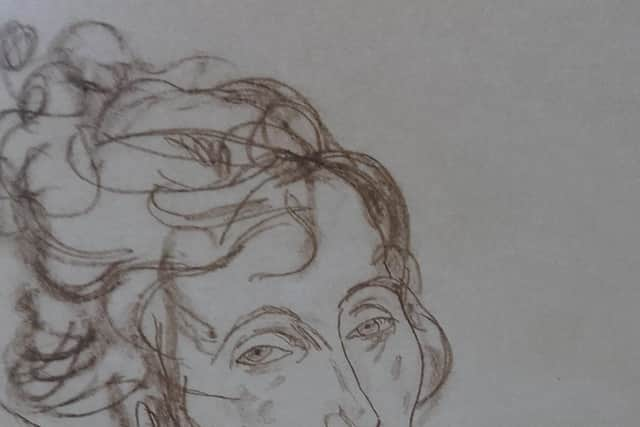

Hide AdLeslie sent me a copy of a tragic portrait which Schiele drew “of his pregnant wife Edith” and explained that Schiele drew the portrait “the night before Edith died of the Spanish Flu pandemic.”

Leslie added: “It’s regarded as Schiele’s last drawing. He died two days later.”

Leslie has seen the drawing where it hangs in Vienna’s Leopold Museum in Austria and is creating a series of paintings and sketches during the lockdown, some of them based on Schiele’s work. He’ll share more about his ‘lockdown drawings’ in the near future.

Egon Schiele was just 28 when he died, but in his short life he created over 3,000 drawings, paintings, self-portraits and nudes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe is described by art historians as an ‘agent provocateur of the modernist era’ and ‘a taboo-busting rebel whose art looks like it was made yesterday.’

He was born in 1890 in Austria.

His father was the station master of the Tulln station in the Austrian State Railways system and Egon loved drawing trains as a child.

In 1906 Schiele went to an Art School in Vienna where the famous Viennese artist Gustav Klimt had studied.

In 1907 Klimt befriended and mentored Egon and bought the young artist’s drawings.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1915 Schiele married Edith Harms, who lived near his studio in Vienna.

Three years later on 28 October 1918 Edith died, six-months pregnant, having succumbed to the global pandemic which took husband Egon three days later.

And there’s more here today about the missionary furloughs mentioned on this page last week.

Workers’ furloughs are much in the news today due to the lockdown but they’ve been common in missionary circles since at least the early 1800s when church missionaries took a year off ‘on furlough’ every four of five years to come home from foreign lands.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDuring their ‘working holiday’ they travelled around countless public meetings held in halls and churches, describing their missionary work and raising funds for their mission.

They also often used their ‘time-off’ to write books and articles about their work.

I sometimes can’t tell who sent the e-mails, or where they’re from, but thank you to the reader who forwarded a copy of an old Presbyterian Furlough Manual dated 1921.

It makes for intriguing reading - “the importance of the furlough in relation to missionary efficiency cannot be overstated” - and deals with the missionaries’ time at home “in a truly scientific fashion.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCompiled by a large committee of experienced Presbyterian clergy and missionaries the lengthy list of topics in the manual includes chapters entitled The Various Values of the Furlough, Preparation for the Furlough, the Length and Frequency of Furloughs, and Practical Management issues such as ‘mental energising’ and ‘physical well-being’.

I’ll peruse the document in more detail and share it here next week.

Whilst the manual’s focus is on very different matters to those prevalent in today’s lockdowns, the chapters on Utilising Free Time, Living Economically and Freedom from Worry will undoubtedly offer worthwhile advice.

And finally today - regular contributor Selwyn Johnson shares a short note and a photograph - “I am not sure whether you are familiar with Maunchline Ware which was very popular until the 1930s when they ended production.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMaunchline manufactured wood-crafted souvenirs world-wide, and Selwyn’s photo shows one featuring Devenish Tower in Fermanagh.

All will be revealed here next week, plus international reaction to poet Liam Logan’s Ulster Scots Covid-19 advice!