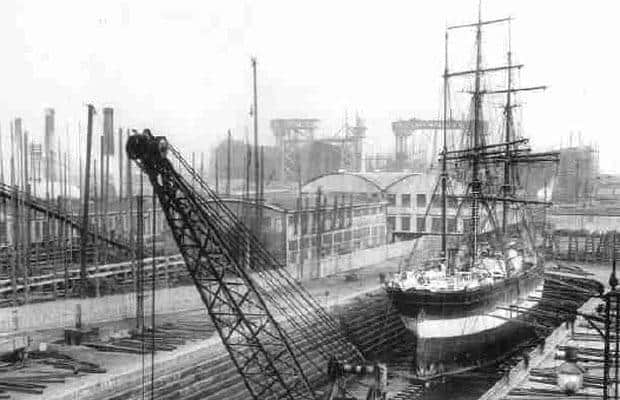

Queen’s researcher to explore how women and children were impacted by the deindustrialization of the shipyards in Belfast

and live on Freeview channel 276

The project is being led by Shonagh Joice, a PhD Researcher from the School of History, Anthropology, Philosophy and Politics at Queen’s University Belfast.

Shonagh said: “The shipyards were a dominant employer in both Belfast and Glasgow, however from the 1960s onwards they were under constant threat of decline, and closure. “With every threat of redundancy, a large cross section of the population was threatened with unemployment.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"It can be assumed that this tumultuous and turbulent period would have impacted entire family units.

"Mental health reports have highlighted the strain that redundancy and unemployment had on couples, spouses, and households.

“It is understood in Glasgow that a lack of alternative work led to large numbers of unemployment within the city.

"However, this research does not exist for Belfast.

"This new research seeks to understand if this was the case in Belfast, as Harland and Wolff received increased financial support from the government due to the social and political climate within Northern Ireland at the time.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe project is looking to interview women who were connected to Harland and Wolff, as an employee, through a husband/father/or family member, or as a worker in the community, post-1970. It aims to document the variety of experiences that accompanied the downsizing of this major industry.

Key areas of interest include:

How did life change?

How did they adapt?

How did employment patterns change?

How did life within the household change?

Or alternatively, did nothing change at all?

“Evidence from other post-industrial areas illustrate that during decline, and after closure, women played an active role within the household economy, taking on increased hours within employment, and sometimes becoming the familial breadwinner,” Shonagh added.

“To-date, women’s experiences of industrial closure have not been documented, particularly life in the home or community.

"Women often feel it is not their story to tell, or that they have nothing interesting to say. This is of course not the case.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“This research will shine light on the wider implications of industrial decline and closure, outside of the workplace.

"Coverage and writings of this time-period has widely focused on men, however, it is indisputable that women were also impacted by these events.

"This project provides women with the chance to tell their story, and have it included in a transnational research project that hopes to write a social history of deindustrialization and its long-term impacts.

"It is crucial that women in Belfast tell their story.”

Regardless of our ability to draw a direct causal link, the outbreak of sectarian conflict needs to be viewed in the context of the profound economic challenges that Northern Ireland faced in the 1960s. Between 1962 and 1968, the linen and shipbuilding industries collectively shed about 30,000 jobs. These losses were felt hardest in working class Belfast neighbourhoods like Ballymacarrett, Ardoyne, and the Shankill, which would soon become sites of particularly intense sectarian conflict.

If you are interested in participating or would like more information, please contact Shonagh on email [email protected].