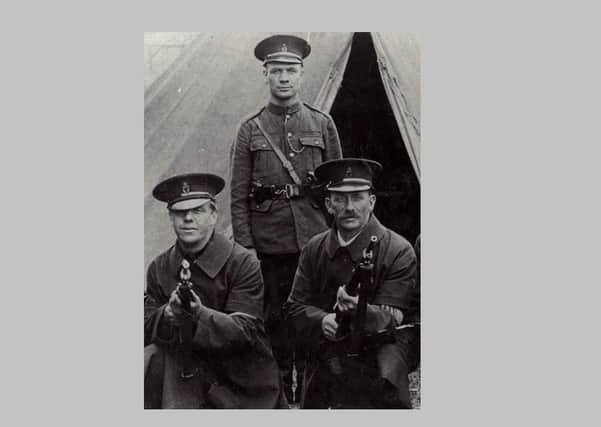

The Ulster Special Constabulary helped establish peace in early years of Northern Ireland

During the course of 1920 much of southern Ireland, especially in Dublin and some counties in Munster, inexorably slid into anarchy and chaos.

Basil Brooke, a Fermanagh landowner and future prime minister of Northern Ireland, witnessed this at first hand as he visited his wife during her confinement in Dublin.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith a view to averting a similar descent into anarchy in Ulster, in April 1920 on his Colebrooke estate Brooke organised Fermanagh Vigilance, which could be regarded as the first step towards reviving the pre-war Ulster Volunteer Force.

In early June 1920 in nearby Lisbellaw George E Liddle pulled together a group in response to the withdrawal of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) from the village which left the locals feeling vulnerable.

Armed patrols were organised to operate on the approach roads to the village and arrangements were made to guard the railway station, the court house and the abandoned police barracks. Lookouts were posted in the tower of the parish church.

The stationmaster was asked to report immediately if the telegraph wires to the station were cut as this was regarded as a reliable indication that the village was about to come under attack.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe attack on Lisbellaw (preceded, as anticipated, by the cutting of the telegraph wires) took place on June 8/9, the very first night that the locals had put their scheme into effect.

An IRA advance party was allowed to reconnoitre the village without interference. They were even allowed to bring in their cans of petrol and place them round the courthouse before the alarm was given by ringing the church bells. The 50 terrorists were completely taken by surprise. Remarkably, in the ensuing firefight only three men were wounded.

The insurgents fled, abandoning their revolvers, bicycles and torches.

One group retreated towards Enniskillen and another fled in the direction of Tempo Mountain.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMessages had been sent by the locals summoning the assistance of the RIC and the army from Enniskillen but they were certainly in no hurry because they did not appear until lunchtime the next day.

The soldiers then attempted to disarm the Lisbellaw men who had successfully defended the village. After heated exchanges the exasperated locals persuaded the troops that they would be better employed pursuing the terrorists.

At the Twelfth demonstration at Finaghy, Sir Edward Carson, the unionist leader, deploring the state of the country, advised the government: ‘If ... you are yourselves unable to protect us from the machinations of Sinn Fein ... we will take the matter into our own hands. We will reorganise’.

Shortly afterwards, the Ulster Unionist Council entrusted the responsibility of re-activating the pre-war UVF to Lt-Col Wilfrid Spender.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSir James Craig also demanded the creation of a special constabulary but effectively the purpose of his call was to legitimise what was already in existence.

In formal terms the creator of the Ulster Special Constabulary was Sir Ernest Clark who in September 1920 was appointed additional Assistant Under-Secretary in the Irish Office with administrative responsibility for the area which was to form Northern Ireland.

Sir Ernest recognised the urgent necessity of creating an armed force of special constables to deal with the rapidly deteriorating situation. Using powers available to him under the Special Constables Act (1832) he set about his task.

Within five weeks of his appointment, on 22 October 1920, he published details of the new Special Constabulary which was to comprise three categories:

(i) A Specials

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThese were to be paid and full-time but would only serve within the division where they were recruited. They would have the same arms and equipment as the police.

(ii) B Specials

These were to be part-time and unpaid, apart from a small allowance for service and wear and tear of clothes. Their arms were to be determined by the police county commander. They were to do ‘occasional duty, usually one evening per week exclusive of training drills, in an area convenient to members, day duties being required only in an emergency’.

(iii) C Specials

They were to be a reserve force and were only to be called out in case of emergency.

The early years of Northern Ireland’s existence were violent as the IRA sought to strangle the new state at birth. Between 21 June 1920 and 18 June 1922 it has been calculated that 428 people were killed and a further 1,766 wounded.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOver half of these deaths occurred in 1922. In that year 232 people, including two unionist MPs, were killed, nearly 1,000 wounded, and more than £3 million worth of property destroyed.

The effectiveness of the B Specials in quelling IRA activity was acknowledged by the commander of the IRA’s 3rd Northern Division who admitted that deployment of the B men had forced him to abandon flying columns in Antrim and Down within two weeks of a planned offensive in the summer of 1922.

In west Ulster the IRA’s 2nd Northern Division and in Armagh the 4th Northern Division suffered the same experience. Quite simply, the terrorists could not operate freely and with impunity because they never knew when or where they might run into a USC patrol or check point.

By July/August 1922 the IRA insurgency had been crushed. The services of the A Specials were dispensed with and the C Specials were never heard of again. Only the B Specials survived.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey acquired uniforms, continued to perform duty once a week and to train and drill. Through platoon, inter-county and province-wide shooting competitions many B men became very proficient marksmen.

There were disturbances in a variety of centres in the early 1930s but apart from serious rioting in Belfast in the early 1930s — which was mercifully of short duration — there was nothing remotely comparable to the murder and mayhem unleashed by the IRA in the early years of Northern Ireland’s existence.

If these years were largely peaceful and uneventful, it was due to the selfless devotion of the men of the USC.

——— ———

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith the coronavirus lockdown having a major impact on many of our advertisers — and consequently the revenue we receive — we are more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription.

Subscribe to newsletter.co.uk and enjoy unlimited access to the best Northern Ireland and UK news and information online and on our app. With a digital subscription, you can read more than 5 articles, see fewer ads, enjoy faster load times, and get access to exclusive newsletters and content. Visit https://www.newsletter.co.uk/subscriptions now to sign up.

Our journalism costs money and we rely on advertising, print and digital revenues to help to support them. By supporting us, we are able to support you in providing trusted, fact-checked content for this website.

Alistair Bushe

Editor