There’s still public legacies of WWI pandemic shown by ailing artists

The virus and the circumstances were very different but it’s being mentioned again as mankind faces another pandemic.

Remarkably, the countless millions of ‘flu deaths just over a century ago had, until recently, been mostly forgotten.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSpecialist war-historians contrast the worldwide, large-scale commemoration and memorialisation of WWI with the pandemic that ensued.

There are no museums, heritage centres, exhibitions, national monuments, tours or Remembrance Days dedicated to the pandemic!

Commemoration of the 1918-19 tragedy is mostly of a personal nature - grieving for the lost loved-ones whose names and faded photos are generally confined to family archives.

But there are more public legacies of the WWI pandemic still resounding over a century later.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

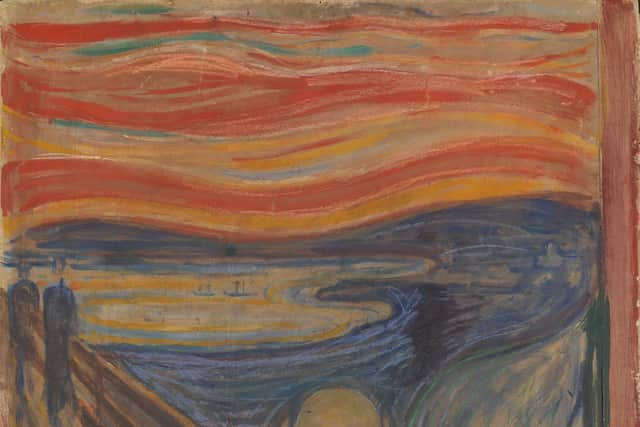

Hide AdThe ubiquitous fancy-dress mask based on a painting called The Scream by Norwegian artist Edvard Munch, is said to be the second most famous image in art history, after Leonardo’s Mona Lisa.

Munch painted a number of versions of his macabre, eerie-faced figure between 1893 and 1910.

Standing on a bridge beneath a swirling, blood-red sky, the figure clasps its head in its hands, crying out in despair, with two other figures lurking behind.

Munch, a troubled character with severe mental issues, was scarred by illness and the early deaths of his mother and sister.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe revealed the inspiration for The Scream in his diary in 1892.

He was out walking with two friends - “the sun was setting, suddenly the sky turned blood red. I paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence - there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city. My friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety, and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature.”

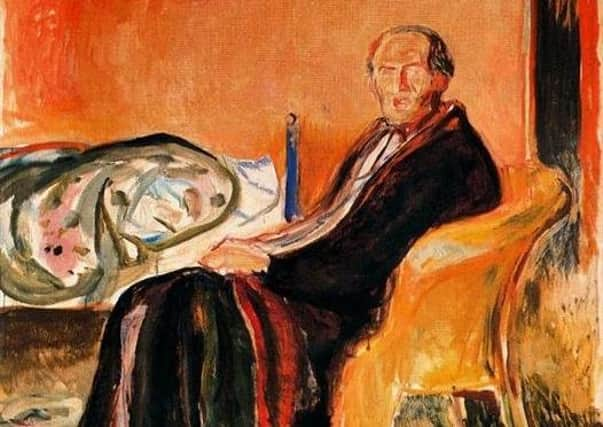

Munch’s lesser-known but similarly harrowing self-portrait after the Spanish Flu is one of the few works of art by anyone that depicts the 1918-19 pandemic.

In a series of studies, sketches, and paintings, Munch detailed the various stages of the disease.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdArt historian Øystein Ustvedt describes the “sick, incapacitated artist who meets our gaze” in the painting.

“His hair is thin, his complexion is jaundiced, and he is wrapped in a dressing gown and blanket…he sits in a wicker chair in front of his unmade sickbed…the room seems narrow.”

He recovered, continued painting, and one of his last works - self-portrait between the Clock and the Bed painted between 1940 and 1943 - marked the end of a prolific output that totalled around 1,750 paintings, 18,000 prints, and 4,500 watercolours, in addition to sculptures, graphic art, theatre designs and film projects.

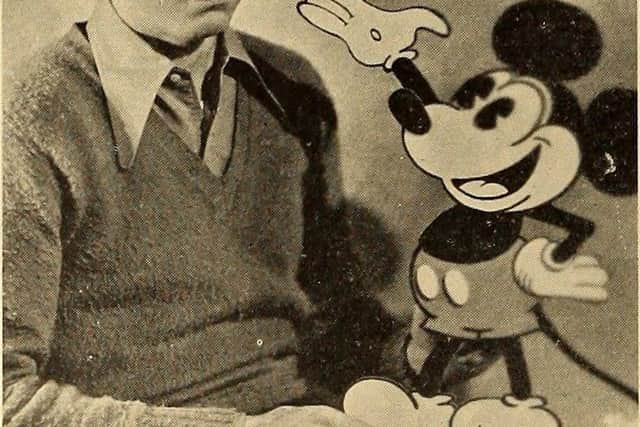

Another artist whose life was changed by the 1918-19 ‘flu, though with a very different creative style to Munch, left us with one of the 20 th Century’s greatest loved fictional characters.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome historians say that if Walt Disney hadn’t caught the virus we might never have had Mickey Mouse!

Even though he was underage, Disney lied about his birthday and signed up for the Red Cross Ambulance Corps during WWI.

When he succumbed to the ‘flu he was shipped back to the USA, away from the dangers of working with injured soldiers on the front lines, where many ambulance workers perished.

Mickey Mouse made his (initially unhailed) debut in May 1928.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOther notable survivors of the ‘flu included British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, US President Woodrow Wilson, Mahatma Gandhi and Kaiser Willhelm II of Germany.

It’s said that when Lloyd George was badly smitten before the end of World War I his illness was kept secret in case the news would damage British morale and encourage the enemy.

There was a host of other famous names from all walks of life who recovered and made their mark on history in one way and another - Groucho Marx, Haile Selassie, TS Eliot, Lillian Gish, Franz Kafka, DH Lawrence, Béla Bartók, Ezra Pound and Amelia Earhart.

Along with Edvard Munch, Pulitzer Prize-winner, Nobel-nominated and multi-award winning writer Katherine Anne Porter drew on her experience of the ‘flu in her work.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe American journalist, essayist, short story writer, novelist, and political activist was hospitalised in Denver during the pandemic.

Her experience was reflected in her trilogy of short novels, Pale Horse, Pale Rider (1939), for which she received the first annual gold medal for literature in 1940 from the Society of Libraries of New York University.

Porter’s story is told by a woman with the ‘flu who is tended to by a young soldier.

While she recovers, he contracts the disease and dies. Using part of Porter’s book-title for her recent publication ‘Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World’, author Laura Spinney notes that there are “very few cemeteries in the world that, assuming they are older than a century, don’t contain a cluster of graves from the autumn of 1918 - when the second and worst wave of the pandemic struck - and people’s memories reflect that.

But there is no cenotaph, no monument in London, Moscow, or Washington.