A pariah in his lifetime, Karl Marx's ideas became the '˜crack cocaine of the left'

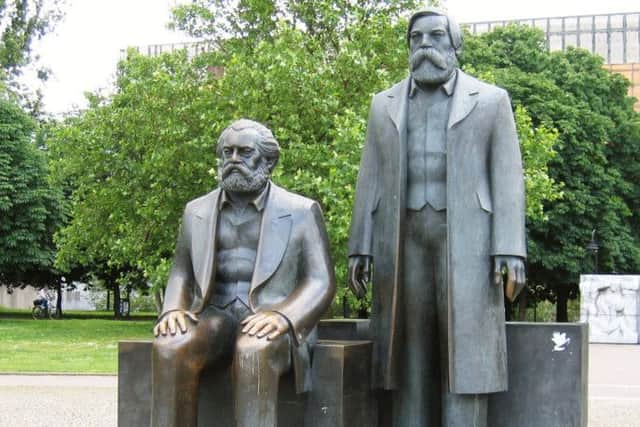

Near Alexanderplatz in what was once East Berlin there is a double statue of Karl Marx sitting and Friedrich Engels standing.

Only dating from 1986, fervent East German communists were outraged by the memorial’s ‘lack of heroic militancy’ and complained bitterly that the founders of ‘scientific socialism’ were depicted as two OAPs.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter German unification in 1990, graffiti artists spray-painted it with the slogan, ‘Next time it will be better.’ Given the millions of deaths and human misery for which Marxism has been responsible, let us hope there never will be a next time.

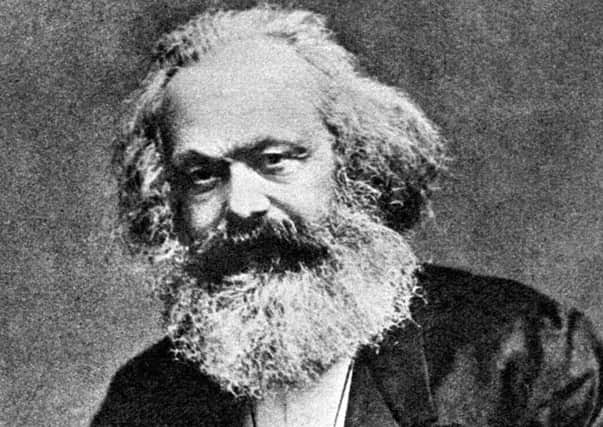

Marx was born on May 5 1818 into a German-Jewish family (which had embraced Lutheranism) in Trier. His father was a successful lawyer and Karl studied law at the universities of Bonn and Berlin. At the former he was idle but at the latter he applied himself to his studies and was greatly impressed by the philosophy of Hegel.

In 1841 he was awarded a doctorate from the University of Jena. After a brief spell as editor of a liberal newspaper in Cologne, Marx and his wife, Jenny von Westphalen, moved to Paris, a hotbed of radical politics. There he became a revolutionary communist and encountered Friedrich Engels.

Their first meeting in 1842 was not a success. Neither was impressed by the other. Two years later they met again. This time ‘their conversation lasted for 10 intense, red-wine fuelled days and nights during which they forged one of history’s most memorable friendships’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdExpelled from France, Marx spent two years in Brussels, where his partnership with Engels grew stronger. They co-authored ‘The Communist Manifesto’ (1848) in which they asserted: ‘The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles’.

Despite its arresting opening – ‘A spectre is haunting Europe – the spectre of communism. All the powers of old Europe have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this spectre: Pope and Tsar, Metternich and Guizot, French Radicals and German police-spies’ – it was not exactly a best-seller. It disappeared without trace for 24 years.

In 1849, Marx moved to London. Although he assumed his stay in London would be short, it proved to be permanent. He spent 30 years in the Reading Room of the British Museum while his family lived in poverty. Their poverty was greatly alleviated by the generosity of Engels. Unlike Marx, Engels became a very wealthy and successful man. Marx could be regarded as a parasite.

The first volume of Marx’s most important work, ‘Capital’, was written in German and published in his lifetime, while the remaining volumes were edited by Engels after Marx’s death. ‘Capital’ was originally no more successful than ‘The Communist Manifesto’. Published in 1867, sales were painfully slow. It was not even translated into English until 1886.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad‘Capital’ enjoyed its greatest initial success in Russia in the 1870s. Tsarist censors felt no need to prevent publication of this ‘strictly scientific work’, assuming that few would read it and even fewer would understand it. Contrary to expectations, including the author and censors, it led to revolution in Russia earlier than in the western industrialised European societies to which ‘Capital’ was directed. Russian reactionaries and revolutionaries alike welcomed it as an exposé of the western capitalist system they both wished to avoid.

In his final years, Karl Marx was in poor health (which he described as ‘the wretchedness of existence’). He was distressed by the death of his wife in 1881. He died on March 14 1883 and was buried at Highgate Cemetery in London. Only 11 people attended the funeral.

His tomb – the present structure was only erected in 1956 – bears two quotations. The first is the final sentence from the Communist manifesto: ‘WORKERS OF ALL LANDS UNITE.’ The second comes from the ‘Thesis on Feurbach’: ‘The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways – the point is to change it’.

During his lifetime, Marx’s relationship with practical politics was virtually non-existent but after his death his social, economic and political ideas gained rapid acceptance with European socialists. His ideas continue to enjoy great prestige in academia in a wide range of disciplines.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUntil comparatively recently almost 50% of the world’s population lived under regimes that claimed to be Marxist. Leaders as diverse as Lenin in Russia, Mao in China, Fidel Castro in Cuba, Pol Pot in Cambodia, Tito in Yugoslavia, Nkrumah in Ghana and Chávez in Venezuela either claimed to be Marxists or to have been influenced by Marx. Some allege that a number of these individuals significantly reinvented Marx to such an extent that Marx might be hard pushed to recognise his influence on their political thought.

Many of these Marxists have presided over regimes which have been responsible for the deaths of millions in the pursuit of their Marxist ideology. Tristram Hunt, the historian and former Labour MP, contends that ‘in no intelligible sense can Engels or Marx bear culpability for the crimes of historical actors carried out generations later, even if the policies were offered up in their honour’. Yet Marxism seems to require repression, coercion and totalitarianism to function. Although far from perfect, the evidence overwhelmingly suggests that human freedom and the meeting of human needs are better served by capitalism and liberal democracy than Marxism.

A striking feature of Marx’s writing is his hostility to Christianity and religion. For example, in the preface to his ‘Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right’ (1843) Marx wrote:

‘Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world … It is the opium of the people. The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions’.

Although Marxism has failed as a political and economic system, ironically it flourishes as a secular religion. Perhaps Marxism ought to be regarded as the crack cocaine of the Left.