Unpasteurised milk supporters champion its multiple benefits

Unpasteurised milk has many supporters who cite multiple benefits to its consumption, including helping with skin and asthmatic conditions.

As a result of an unsubstantiated, suspected case of e-coli, the Errington dairy was closed last year, by the Food Standards Agency in Scotland. The claim remains unproven and a global campaign to support the dairy continues to gain momentum. There are many raw milk producers throughout Ireland whose products are showcased and celebrated by delis and on menus the length and breadth of the the island and across Great Britain.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

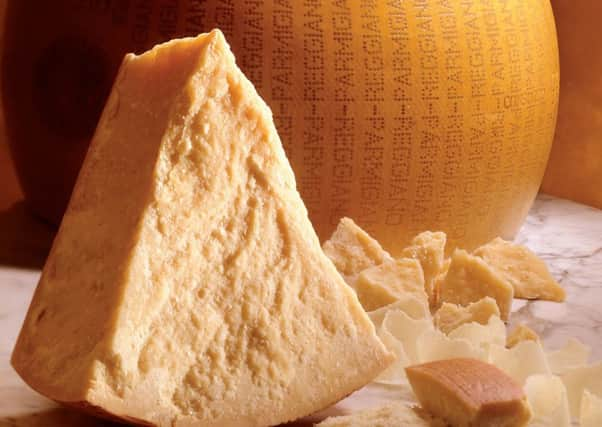

Hide AdParmigiano-Reggiano or Parmesan cheese is an Italian raw milk cheese. It has Protected Designation of Origin status (PDO) and can only be produced in an area around the north of the country that encompasses the towns of Parma, Modena and Bologna. The milk used is a combination of the morning milk and the skimmed variety from the evening before. I had the privilege of being invited to the Parma 2064 Dairy last week, situated in the village of Fidenza, near the city of Bologna in northern Italy, to see this seven century old artisan tradition in practice.

The milk is warmed to 33oc and then calf rennet (an acid from the stomach that means Parmesan is not suitable for vegetarians) is added. The mixture is allowed to curdle, broken up into small pieces and then the temperature raised again. The compacted resulting curd is collected in a piece of muslin and two workers cradle it to make it round. It weighs around 45kg at this stage. It’s then pressed tightly into a plastic mould. After a couple of days it’s transferred to a stainless steel mould. In another two days a plastic belt, imprinted with the name, plant number, month and year of production is wrapped round the cheese and then buckled tight within the metal mould. The cheese is then brined for 20-25 days and transferred to an aging room.

The warehouse I saw was filled with rows of these cheeses on shelves that reached as high as the ceiling– it was like a cathedral for cheese.

When the product is 12 months old it’s inspected by a group of experts called the Consorzio Parmigiano-Reggiano where a master grader taps the cheese to ensure there are no voids or undesirable cracks.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWe were treated to the impressive spectacle of a Parmesan being opened. The caramel coloured, weighty wheel is laid on a circular wooden stool and the top sliced in half with a short, hook like knife.

Daggers are inserted at strategic places and the cheese is cut in half to expose a beautiful creamy inside. This crystalline, rich delight is best served with a glass of cool Prosecco. Exactly what we did, causing a crackly, cheese burst in the mouth.

Closer to home Ken and Elaine Hanna produce raw milk from their Jersey cow herd.

Despite not liking milk, I’ve made a ricotta like cheese from their product which was deliciously creamy and irresitible. Making cheese like this isn’t difficult but richly rewarding.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCheesemakers send the whey leftovers to feed lucky pigs but in my first recipe the resulting whey is used for a piadina bread.

The second recipe is for a baked ricotta with onions and garlic. Spread it on the warm Italian bread for a lovely starter or snack.

The Hannas, along with other skilled food producers, will be at Comber Market, in the Square in the town, on Thursday, 2nd February from 10am. You can try their traditional milk for yourself.