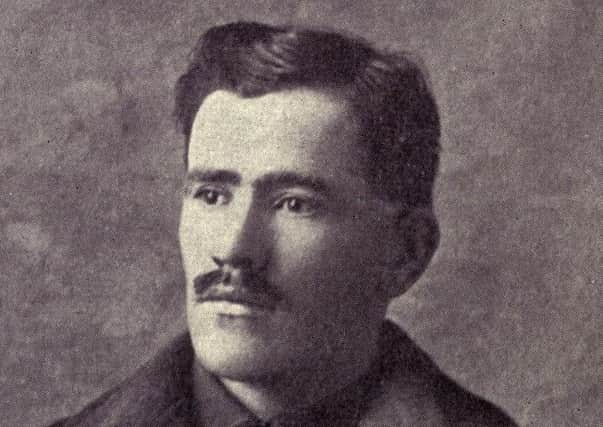

Francis Ledwidge, Irish nationalist and poet who died on the Western Front

Born in the Boyne Valley in 1887, Francis Ledwidge was the eighth of the nine children of Patrick Ledwidge, a farm labourer, and his wife, Anne Lynch.

Although the family was poor, Francis grew up in a home where education was highly valued.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPatrick’s premature death when Francis was only five forced his widow and young family out to work.

Francis left the local national school aged 13, but continued to educate himself as best he could.

He wrote poetry, often on gates and fence posts. To earn a living, he worked at a variety of jobs: as a farmer’s boy, as a shop assistant, as a yard boy, as a road mender and a copper miner.

In 1910 he began to have his poetry published in the Drogheda Independent.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1912 he sent poems to Lord Dunsany, a Meath landowner and a man of letters (who would become a prolific author and dramatist), and asked for help with getting his poetry published. After a delay (due to Dunsany being in Africa on a hunting trip), Dunsany invited the poet to his home, and they met and corresponded regularly thereafter. Dunsany was so impressed that he helped with the publication of his poems, and provided Ledwidge with an entrée into literary society.

Through Dunsany he became acquainted with W B Yeats and Katharine Tynan. Dunsany gave him money, literary advice and access to his library.

The following year Francis obtained a temporary job as secretary of the Meath Labour Union.

The year 1913 also witnessed the formation of the Irish Volunteers, a southern nationalist counterpart to the UVF. Francis and his brother Joseph founded the local corps in Slane.

They drilled twice a week and on Sundays.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe outbreak of the Great War precipitated a split in the Irish Volunteers.

In return for the third Home Rule bill reaching the statute book and in his belief that a common sacrifice for the British war effort would form the basis of Irish unity, John Redmond said in an impromptu speech at Woodenbridge, Co Wicklow, in September 1914 that Irishmen should ‘go where ever the firing line extends, in defence of right, of freedom and of religion in this war. It would be a disgrace forever to our country otherwise’.

Four days after Redmond’s Woodenbridge speech, Eoin MacNeill and the executive of the Irish Volunteers repudiated Redmond.

The seceding minority led by MacNeill retained the name Irish Volunteers and determined to resist any attempt to force Irishmen ‘into military service under any government, until a free national government of Ireland is empowered by the Irish people to deal with it’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFrancis originally supported MacNeill’s position (and was accused by the local Board of Guardians of being pro-German) rather than that of Redmond. Francis originally contended: ‘The men to follow were the men who started the movement and not Mr Redmond, who, after the movement had been organised, tried to get hold of it. So far as Home Rule is concerned they were as far off it today as ever.”

Yet on October 24, 1914, he joined the 5th Battalion of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers.

Nationalists often unfairly blame Lord Dunsany for Francis’s volte face but the truth is otherwise because Dunsany had actually tried to discourage Francis from enlisting by offering him a stipend.

For a time he found himself in the same unit as Dunsany.

Dunsany helped him with the publication of his first collection, Songs of the Fields, which met with critical success upon its release in 1915.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFrancis’s enlistment may have flowed from his moral and political convictions because he professed to believe that nationalist Ireland must stand against the tyranny of Kaiser Wilhelm’s Second Reich: “I joined the British Army because she stood between Ireland and an enemy common to our civilization, and I would not have her [Britain] say that she defended us while we did nothing at home but pass resolutions.”

A more personal consideration may have been paramount.

He may have joined up because his sweetheart Ellie Vaughey, who, as the daughter of a local farmer was out of his league, had rejected him and found a new lover, John O’Neill, whom she later married.

Ellie died in childbirth in 1915. The news of her death prompted one of Francis’s finest poems, ‘To One Dead’.

He served in the 10th (Irish) Division at Gallipoli and in Salonika and kept in touch with Dunsany, sending him poems.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was injured in December 1915. The following year he was court-martialled for extending his leave without authorisation, expressing sympathy for the insurgents of Easter Week and being drunk in uniform.

Now attached to 1st Battalion of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, in December 1916 he was posted to the Western Front.

On July 31, 1917, the same day as the beginning of the Battle of Third Ypres, Francis and five fellow soldiers were repairing a road (‘his original civilian profession’) at Pilkem when a stray enemy shell exploded among them, killing them.

All six men were originally buried where they had died – at Carrefour de Rose. Francis’s remains were subsequently reinterred in the nearby Artillery Wood Military Cemetery at Row B, Grave 5.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPolitically, Francis was left wing and nationalist in outlook but such a bald statement does not do justice to the complexity of his position.

He was also a British soldier and a friend of Lord Dunsany, a conservative and unionist in politics, who was the holder of the second oldest title in the Irish peerage.

Francis was also friendly with Thomas MacDonagh, a fellow poet and one of the signatories of the 1916 Proclamation.

His best known poem is probably ‘Lament for Thomas MacDonagh’.

Selected poems (1993), edited by Dermot Bolger, has a foreword by Seamus Heaney, who also wrote an elegy for Francis.