High-wire romancing and telegraphic poetry by high-powered Antrim publisher

Since the organisation was first mentioned on this page last year more than a few readers have expressed more than an embryonic interest in telegraph poles.

It’s hard not to be enthused (and/or amused!) by a society that eloquently proclaims: “All wire-carrying wooden poles have an essence of whimsical poetry all of their own. There they stand, silent sentinels forever observing us who scurry about beneath them, oblivious.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut it seems that poetry and eloquence are as deeply rooted in the telegraphic industry as the poles – mostly thanks to a man from Northern Ireland.

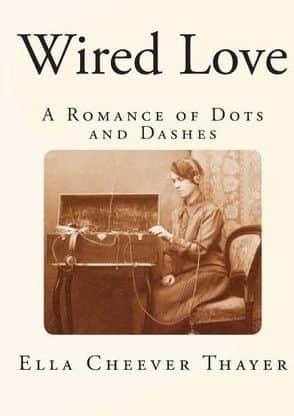

On Monday morning on BBC Radio Four a drama-documentary entitled ‘Wired Love’ recounted the absolutely intriguing story of an American book with the same name about “the Romance of Dots and Dashes” published in 1879.

It was a ground-breaking book written by a previously unknown author called Ella Cheever Thayer.

Wired Love is the story of a long-distance romance conducted over the telegraph wire – aptly referred to as “the Victorian Internet”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWired Love’s Manhattan publisher William John Johnston hailed Thayer’s book as “a bright little telegraphic novel” that recounted “the old, old story – in a new, new way”.

It may have been fiction, but it was grounded in Victorian reality.

Male and female workers in the burgeoning telegraphic industry, though separated by endless miles of wires strung along countless wooden poles, sometimes fell in love.

At least one wedding was conducted over the wires.

And Wired Love’s publisher William John Johnston came from Ballycastle.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

Formerly a telegraph operator himself, in the 1870s and 1880s Johnston collected and sold stories, poems, and plays written by and for telegraph operators.

This was just one branch of the Co Antrim entrepreneur’s very successful New York publishing business.

When he died aged 54 on 28 April 1907 the New York Times obituary for William J Johnston stated that the “well-known publisher died at his home, 774 West End Avenue, after a short illness”.

The obituary added that he was “born in Ireland in 1853, and educated there. In 1868 he came to America, and shortly afterward founded The Operator, an electrical paper, now known as The Electrical World, and the first paper of its kind in this country. He leaves a widow, four sons, and four daughters”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

Johnston’s papers, and Ella Cheever Thayer’s book, were a small part of his publishing empire.

The Ballycastle-man also published The Engineering and Mining Journal, and at the time of his death he was also the owner and publisher of The American Exporter.

Johnston was also a member of the American Institute of Mining and Engineers, the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, the Hardware Club, and the Sphinx Club, an organisation for advertising and marketing professionals.

Monday’s Radio Four programme included the voice of Britt Peterson, Johnston’s great-great-granddaughter.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMs Peterson referred to her eminent relative’s own writings, such as those compiled in his 1877 anthology ‘Lightning Flashes and Electric Dashes’.

Like members of the Telegraph Pole Appreciation Society – Johnston was both passionate and poetic.

The short story that he wrote in the 1877 anthology, entitled ‘A Centennial-Telegraphic Romance’, begins with two telegraph operators – Sydney and Eva – flirting joyfully in Morse code.

But a line from a 19th century poem restrains Sydney’s romantic intentions – “Hope’s gayest wreaths are made of earthly flowers”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAccording to Britt Peterson, great-great-grandfather Johnston came to New York from Ballycastle as a teenager, probably sometime in the late 1860s or early 1870s.

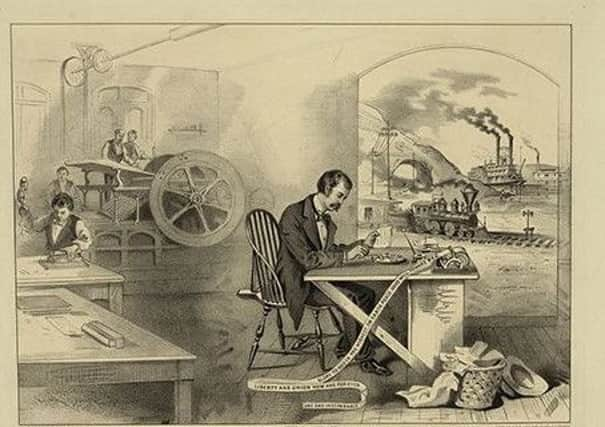

While working as a telegraph operator for the Western Union William and a few workmates started a four-page bi-weekly paper called The Operator.

Western Union objected when the paper ran an editorial objecting (extremely mildly says Peterson) to a company-wide salary cut so Johnston resigned, taking The Operator with him.

From then on, 23-year-old Johnston – “self-educated, a bombastic and sometimes pedantic writer with a fondness for classical flourish” says Peterson – was solely in charge of The Operator.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe ran stories and poems, often of a romantic nature and mostly written by telegraph operators, packaged between in-house gossip, news, and editorials.

Johnston’s editorial goal, as he explained in the anthology Lightning Flashes and Electric Dashes, was to give “telegraphy a literature of its own”.

As the telegraphic industry began to experience profound technological and financial changes, Johnston advertised money-raising wares amongst The Operator’s classifieds.

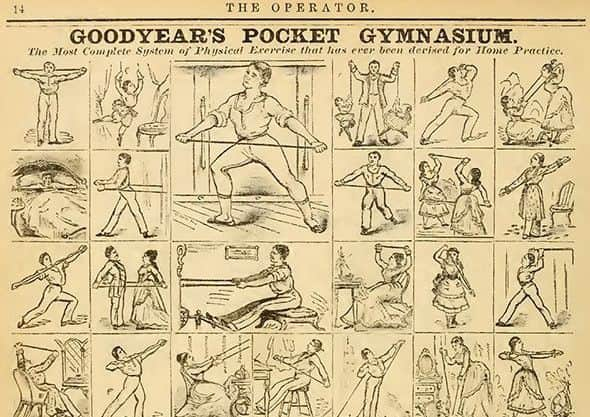

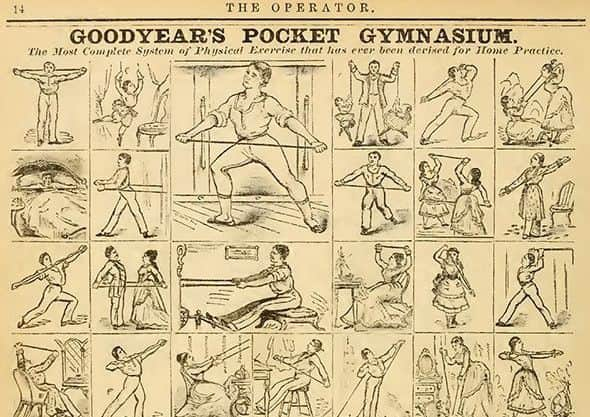

One was a self-improvement tool called ‘Goodyear’s Pocket Gymnasium’, illustrated in advertisements with drawings of bulky, moustachioed men in tights and women in pinafores and frilly gowns exercising their arms by pulling on rubber straps.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe ads suggested that regular use of the elasticated equipment would “prevent telegraphers from dying of consumption” – an illness they risked developing by working long hours in cramped and unventilated spaces.

Business continued healthily, Johnston married his landlord’s daughter, settled in Greenwich, Connecticut, and started having children.

In 1883 he published a new weekly called The Electrical World, starving The Operator of advertising.

In 1899 he left both publishing ventures behind, along with his first and second wife and eight children, and went off alone on a world tour.

He returned to the United States, published trade magazines like Mining and Metallurgy, and died of a sudden cerebral haemorrhage in 1907.