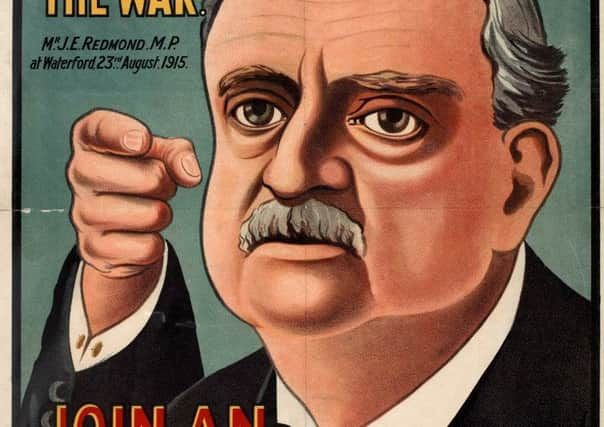

John Redmond: the man who convinced the Irish to fight in World War One

Less than a year before his death, John Redmond observed: “The life of a politician, especially of an Irish politician, is one long series of postponements and compromises and disappointments and disillusions.

“As we grow old, and this of course bears in upon me, we feel our ideals grow dimmer and more blurred, and perhaps many of them disappearing one by one.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe continued: “And many of our cherished ideals, our ideals of a complete, speedy and almost immediate triumph of our policy and of our cause have faded, some of them almost disappeared.

“And we know that it is a serious consideration for those of us who have spent 40 years at this work, and now are growing old, if we have to face further postponements...”

In 1912 William Moore, the Unionist MP for North Armagh, told the House of Commons: “We have prospered under it [the Union] and we will take nothing less.

“And instead of the sentimental humbug about Ireland’s well-being … we maintain our own ideals because we are connected with Britain by ties of blood … religion and history; and we object to being swallowed up in the claim … that we should come into [Redmond’s] fold because we live in Ireland.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough Redmond’s mother was a Protestant (she converted to Roman Catholicism but remained a unionist, albeit a southern Irish one) and his second wife was an English Protestant, he never understood Ulster unionists and the depth of their hostility to Home Rule.

On the strength of his own experience of and contacts with southern Irish unionists Redmond fondly supposed that if Home Rule came into operation, after a few years the fears of Ulster unionists would be proved groundless, but he never succeeded in persuading them that this was the case.

Ulster unionism remained a formidable obstacle to the attainment of Home Rule and constituted Redmond’s major problem prior to the Great War.

Yet in 1914 Redmond seemed to be on the threshold of achieving his life’s ambition.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe gave his whole-hearted support to the war effort in return for Asquith’s promise to place the third Home Rule Bill on the Statute Book but with its implementation suspended until the end of the war.

His speech on September 20 1914 at Woodenbridge in his Wicklow constituency should be seen in this context. Redmond was not being entirely cynical.

There were personal considerations at play, not least the fact that he had a niece who was a nun in a convent in Ypres.

This gave him a genuine sympathy for ‘little catholic Belgium’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was also a measure of idealism because he believed that joint unionist and nationalist participation in the war effort and their shared sacrifice would constitute the basis of a new Irish unity afterwards.

Nor was this wholly unrealistic.

As early as August 5 1914, Bryan Cooper, the former Unionist MP for South County Dublin, telegraphed Redmond: “Your speech has united Ireland. I join National Volunteers today, and will urge every unionist to do the same.”

He wrote a letter to the Irish Times in the same vein.

In 1915 J H Bernard, the Church of Ireland bishop of Ossory (and future Archbishop of Dublin and Provost of TCD) said that after fighting side by side it would be intolerable for Irishmen to turn against each other.

On May 25 1915 Asquith announced the formation of a coalition government in which Sir Edward Carson became attorney-general.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRedmond was offered a position but declined in obedience to the established nationalist policy of not serving in a British administration without Home Rule being in place.

By doing so Redmond deprived himself of the opportunity to wield significant influence.

Curiously the Dundalk Examiner interpreted Redmond’s refusal to join the government as evidence of weakness: “The Irish Party has been playing a certain game for 10 years.

“The denouement has now come, and it is only too manifest that they cut a sorry figure.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRedmond’s major problem now was that the Great War was not proving to be the short conflict most contemporaries expected, thus delaying the implementation of Home Rule. The political vacuum facilitated the re-emergence of the Irish physical force tradition. This proved fatal to both Redmond and Home Rule.

After the Easter Rebellion in 1916 the Irish Parliamentary Party found itself slowly but surely superseded by Sinn Fein.

Lloyd George’s abortive attempt to solve the Irish Question, undertaken at Asquith’s request, between May and July 1916 unintentionally undermined Redmond’s credibility.

On May 16 1917 Lloyd George, now prime minister, offered Redmond a choice between the immediate enactment of Home Rule for 26 counties and a convention in which to debate the wider future of self-government. Redmond opted for a convention.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn retrospect Redmond might have been wiser to opt for immediate enactment of Home Rule for 26 counties.

Electorally during the course of 1917 Sinn Fein successfully challenged the IPP in a series of by-elections – although significantly not in East Tyrone and South Armagh.

The penultimate year of Redmond’s life was personally grim quite apart from political setbacks. At the beginning of 1917 Esther, his eldest daughter, died unexpectedly in New York at the age of 32.

On June 7 his much-loved brother Willie, the MP for East Clare, died of wounds at the Battle of Messines. On July 12 Pat O’Brien, the MP for Kilkenny City and Chief Whip of the IPP, died.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was also Redmond’s closest friend within the IPP. His death was yet another devastating blow.

Redmond was a man who normally kept his emotions in check in public but at O’Brien’s funeral he broke down and had to be led away from the grave.

Redmond died of heart failure at the age of 62 in London on March 6 1918.

At the graveside John Dillon, Redmond’s successor as leader of the IPP, somewhat optimistically predicted that time would do justice to Redmond’s life’s work and even people who misunderstood him would come to appreciate his greatness.