Men and women who saw worst of Troubles bloodshed speak out

Produced in-house by UTV, and using footage from the station’s rich archive library, ‘Frontline’ looks back at the people and the services which helped to keep Northern Ireland functioning during its most turbulent period.

Interviewees give first-hand accounts of their jobs and how they dedicated their lives to their various professions to keep life moving despite the conflict that was going on.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe series shines a light on five key groups of people: Doctors and nurses in the various casualty departments of the big hospitals who dealt day and daily with the effects of bombs and bullets; the teaching profession who share memories of trying to keep life as normal as possible for children sometimes literally caught in the crossfire; well-known faces from the world of entertainment who give insights into how the industry survived and indeed thrived during the Troubles; social workers who were there to provide that vital support to clients and families living in very desperate circumstances; and key figures from the business community, who talk about the economic impact of the Troubles and how they and their staff continued on undaunted by the destruction to their businesses.

Series producer Sinead Hughes said: “We very much wanted to reflect ordinary life in marking this anniversary. The professions we have highlighted in this series are somewhat the unsung heroes of that time.

“It was an absolute honour for me and the team to speak to the interviewees, most of whom have long since retired from their profession, and who shared their very personal and moving stories.

“All of them were united in their praise for colleagues for their professionalism and dignity during very difficult and trying circumstances.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The series is ‘must watch’ not only for those who lived in Northern Ireland during that time, but also for our younger people who gladly did not have to experience life in that time.”

NI’s doctors and nurses are the focus of the first two episodes in the series which is narrated by UTV reporter Sara O’Kane.

With over 37,000 people shot over the course of the Troubles, and 16,000 injured in bombing attacks, hospital casualty departments were incredibly busy and sometimes chaotic places.

Former nurses Attracta Bradley and Ursula Clifford speak of their time in Altnagelvin and helping people injured during the Battle of the Bogside, and how busy the operating theatres were.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

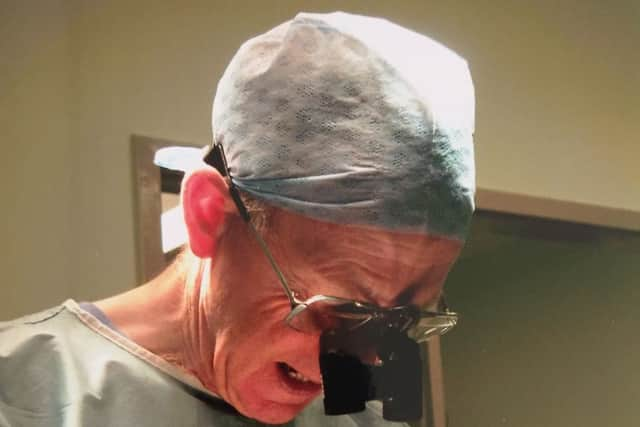

Hide AdFormer consultant anaesthetist in the Royal Victoria Hospital Dennis Coppel, consultant surgeon Professor Roy Spence, and former plastic surgeon Alan Leonard share experiences of treating injuries, and pay tribute to their colleagues for making innovative advances in surgery that would go on to be used worldwide for gunshot and bombing victims.

Despite being seen as safe places, tragedy did strike in hospitals too, and many recount shootings and violence within the hospital walls.

Whether perpetrator or victim, everyone was treated the same, with one nurse commenting: “In pyjamas or a hospital gown they look the same.”

Nurses and doctors from the major Belfast hospitals, Altnagelvin, Omagh and Enniskillen South Tyrone in Dungannon remember the worst atrocities of the Troubles and how in those times staff, whether on duty or off, assisted how they could, and how emergency plans were developed and honed to ensure that all those injured had the best chance of survival.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSinead said: “Doctors and nurses had to deal with harrowing circumstances but their professionalism shines through in all their interviews.”

Attracta Bradley, a former staff nurse at Altnagelvin, said: “Before the Troubles started we were having children falling off bicycles, falling in the playground, fights, there were a lot of drunks coming in at night, just the run of the mill.”

She said they also had to deal with serious injuries from traffic accidents, but nothing to prepare them for what was to come during the conflict.

She said: “The first Troubles I remember would be the Battle of the Bogside and we were thrown in at the deep end that day. We were running from one person to the other.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWorking from a first aid post in the Bogside Inn, she said the level of injuries got worse day by day: “I remember this boy was shot, it was unbelievable. He did survive, but he was quite badly injured. We thought gosh, we’ve gone from stones to bricks now to shooting.”

One of the medical staff working on the day of the Omagh bomb has told how casualties were brought to hospitals in the back of cars and lorries.

Robert Sowney, a nurse at the South Tyrone Hospital in 1998, was in Belfast when he was paged by the hospital and then given a high speed police escort to get to work.

He told the UTV documentary: “I think we made Dungannon in 19 minutes that day. I’ve never, ever driven like that. By the time I arrived at South Tyrone I could hardly stand. Part of it was about what I was going to face, part of it was just having driven like a maniac.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We dealt with I think in total around 36 or 37 casualties, nothing compared to what Omagh Hospital dealt with, they dealt with hundreds, nothing compared with Enniskillen.

“All of our patients bar two arrived in cars, in backs of lorries or trucks, two came by ambulance.

“It was the one time in the whole history of my career in emergency care in Northern Ireland that I felt had come close to, in terms of an emergency care response, being unable to respond totally.

“It was so overwhelming, so many people were injured, so many people were killed.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdConsultant plastic surgeon Alan Leonard recalls the horrific injuries sustained by people in the La Mon bomb in 1978: “I made my way into casualty at the Ulster Hospital not knowing what to expect, I was confronted with eight patients who’d sustained varying degrees of severe burns.

“One of the ambulance men asked me did I want to go and see some of the other people they’d brought in who hadn’t made it which I declined very definitely because I felt I had enough to think about with the eight survivors.

“That was the first night, but in the ensuing weeks all the routine work of the plastic surgery unit stopped and all time in the operating theatre was devoted to operating on these people who were severely burnt.”

Doctors and nurses are the focus of the first two episodes of UTV Troubles documentary ‘Frontline’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFormer consultant anaesthetist at Royal Victoria Hospital, Dennis Coppel, said: “There was no way could I be prepared for the carnage from the bomb explosions.

“That was the thing that I hadn’t any experience of, nobody else had. They were devastating because they involved an awful lot of young people who were caught up in bars and pubs and restaurants, innocent people in bus stations.

“I found I could translate or transform my skills that I used for RTAs and gunshot injuries to the bomb injuries.”

He added: “I remember one of the soldiers got shot on guard at the intensive care unit. I do remember seeing bullet holes all around the entrance to it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Another occasion we had a lot of nurses on duty and I do remember one night coming in and seeing them all lying on the floor and I thought, ‘gosh they’ve been shot’. In actual fact there was shooting going on and they were all advised to lie down on the floor.”

Professor Roy Spence, consultant surgeon at the Royal, recalled a man being shot dead beside him around 1977: “It’s not in the forefront of my brain all the time, but where it happened was very close to my office in the Royal Victoria Hospital complex and if I happen to be walking across that spot and if it happens to be raining, because it was raining when this happened, I can remember the events acutely.

“If you go back to the First World War and you had an injury from an explosion or a shooting it could be a full 24 hours before you could get back from the front to get help. Move into the Second World War that could be half a day. Move into Vietnam with helicopter evacuation it could be two or three hours.

“But remarkably in Belfast about half the patients who were shot or wounded were within the hospital complex in half an hour. Many people survived in Belfast who would not have survived in other conflicts.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSeveral participants in the documentary stressed that all patients were treated equally.

Ursula Clifford, former theatre sister, said: “Mostly we didn’t know but I never ever saw anyone being treated differently because of what happened or where they came from, they were all professionally treated as if they were just any patient.”

Prof Spence said: “All got the same good treatment no matter who they were. Sometimes you had the paradox of someone who had planted a bomb or did some shooting lying also wounded or injured side by side with a policeman or a soldier.”