Belfast Agreement @25: The defeatism of some unionists was one of David Trimble's biggest problems in 1998, writes Henry Patterson

A month before the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement a Northern Ireland Office official reported on a recent opinion poll which showed that most people in Northern Ireland rated the chances of reaching an agreement as very low.

The picture he painted of the unionist community was bleak: ‘Attitudes continue to harden. Community leaders report growing sectarianism in working class areas, while clergy with middle-class congregations report increasing unease about the outcome of the Talks. Throughout the unionist community there is a general feeling of frustration, based on the unshakeable belief that the IRA is not committed to a peaceful settlement and the HMG is making too many concessions to Sinn Fein, and to terrorists, both republican and loyalist.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was nervousness about the form of any North/South bodies and the DUP and Robert McCartney’s rejectionist UK Unionist Party continued to garner support. Many of those who six months before would have been solid supporters of almost any reasonable agreement would now need a lot of persuading if they were to cast a ‘yes’ vote.

The one bright spot was that the Hearts and Minds poll had shown that a sizeable proportion of unionist voters were confident that David Trimble would not sell them out. That a narrow majority of unionists voted ‘yes’ in the referendum reflected their acceptance of Trimble’s argument that the Union was not only safe but stronger because of the UUP’s successes on ensuring that the North/South institutions were not part of creeping reunification process, that the Irish government had committed to the constitutional recognition of Northern Ireland and that all signatories to the agreement were committed to the principle of consent for any change in the constitutional position.

That Trimble was able to lead his party to this point was no mean achievement. When he became leader of the UUP in 1995 his victory was seen in the NIO and much of nationalist and bien pensant opinion as a shift to the right. His negative image was in large part due to the role he played during the Drumcree confrontations between Orangemen, nationalist residents and the security forces in 1995 and 1996.

In 1996 he was central in persuading the Major government and the chief constable that the Orangemen be allowed to march down the Garvaghy Road under RUC protection. For this he was execrated not simply by nationalists but many opinion formers in the UK and further afield. Nancy Soderberg, the White House’s expert on Northern Ireland told an Irish official that Trimble could be disinvited from a meeting in Washington as he deserved punishment: ‘He had single-handedly wrecked the tourism industry – her parents had cancelled a proposed visit.’ The effects of a quarter of century of republican and loyalist terrorism on tourism were not worthy of mention.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut as both the British and Irish governments recognised, if the march had not gone ahead, Trimble’s leadership would have been finished and with it the peace process. That a British government was prepared to stake so much on Trimble was a recognition that, under the sash and the red face, was a serious strategic intelligence. Even the cynical NIO official who attended the first UUP annual conference with Trimble as leader noted the contrast between Trimble’s approach as set out in his address and the pervasive paranoia and pessimism of the party faithful.

In that address rather than indulge in the usual unionist, unspecific allegations of bias on the part of BBC NI he quoted the journalist, Eilis O’Hanlon, who berated Radio Ulster news which, on the morning after the Provisionals under the ‘Direct Action Against Drugs’ flag of convenience murdered an alleged drug dealer, completely ignored the attack. The very fact that Trimble was quoting a Sunday Independent journalist reflected a new outward looking and intellectually confident strand of unionist leadership. It was at this time that he entered into a productive dialogue with southern politicians and opinion formers including John Bruton, Bertie Ahern, Proinsias de Rossa and Eoghan Harris.

He had no fear of the prospect of a new Labour government pointing to a recent interview by Tony Blair where he said his role as prime minister would be as ‘a facilitator for the will of the people of Northern Ireland’ not as advocate of or ‘persuader’ for a united Ireland. The new Labour line on Ireland had annoyed the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs whose representative in the ‘bunker’ – the British/Irish Secretariat at Maryfield – had complained to his NIO counterpart that he found the new Labour spokesperson, Mo Mowlam, ‘flakey’ on these issues i.e. not pro-nationalist like her predecessor, Kevin McNamara.

For Trimble a much bigger problem for the Union than the bias of BBC NI or the ‘hooligan’ tactics of the DUP representatives at the recently elected Northern Ireland Forum, was the defeatist attitude of some unionists. He picked out the leader of the UK Unionist Party, Robert McCartney, who claimed the British and Irish governments were involved in an ‘inexorable process’ to undermine the Union. Trimble thought this ‘rank defeatism, the language of those who say that sell-out and defeat are inevitable’. There was no inevitable slippery slope unless unionists continued with failed policies: the passivity of James Molyneaux’s leadership , the hard faced rejectionism of Paisley and Robinson or the utopian integrationism of the UKUP.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe bedrock of Trimble’s proactive and confident unionism was a conviction that the IRA was being defeated. He expressed it clearly in an interview with a Spanish academic in 1995. The ceasefire was an admission of the failure of armed struggle: ‘Even though the ceasefire may be merely a tactic, the fact that they have had to change their tactic is an admission that the previous tactic has failed…the republican movement is being defeated slowly …from our point of view we have to ensure that while it is winding down that it does not cause any political or constitutional change that is contrary to the interests of the people of Northern Ireland.’

However, it was precisely in the Blair government’s managing of the process to ensure a soft landing for republicans that Trimble’s opponents in his party and the DUP would find the material to destroy him. Trimble seriously misjudged the effects of the early release of paramilitary prisoners on unionist support for the agreement. Even Martin Mansergh ,the key adviser on Northern Ireland to successive Fianna Fail Taoisigh, had surprised Quentin Thomas, the Political Director of the NIO, when he said that he did not expect prisoners to be released until two to three years into a well established ceasefire.

Trimble believed that many prisoners would soon be released under existing remission of sentences legislation. He was also influenced by some Fermanagh unionists who told him they were not that exercised by the prospect of early release as those who murdered their loved ones had never been imprisoned and were openly walking the streets of towns and villages on both sides of the border.

His problems were compounded by the government’s refusal to link releases to decommissioning and the republican movement’s ruthless playing of the possible return to violence card for another six years. But for Trimble the undoubted moral hazard created by early releases and the fudging of the decommissioning issue was more than compensated for by the unalloyed moral imperative of putting an end to violence and saving the lives of hundreds of people who would otherwise have continued to be the victims of loyalist and republican terrorism.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

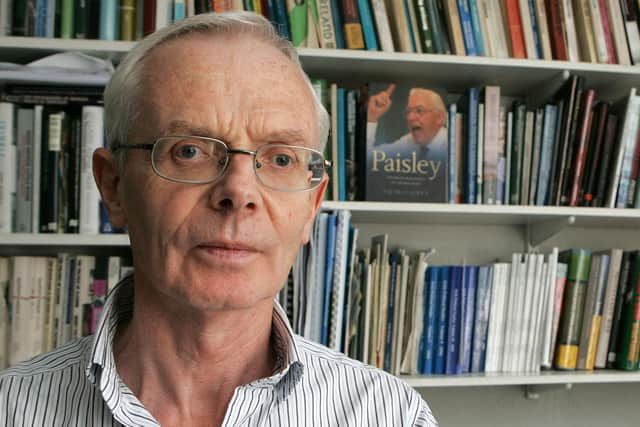

Hide Ad• Henry Patterson is emeritus professor of Irish politics at the University of Ulster and author of Ireland’s Violent frontier: The Border and Anglo-Irish Relations During the Troubles

• These articles reflecting on 1998 and its aftermath continue Monday, including next week the former Stormont minister Dermot Nesbitt. Other coming essays include one by the late Lord Trimble on the damage done to the Belfast Agreement by the NI Protocol, and contributions from Bertie Ahern and Mark Durkan