Alex Kane: Unionism needs to understand Sinn Fein’s appeal before it can deconstruct it

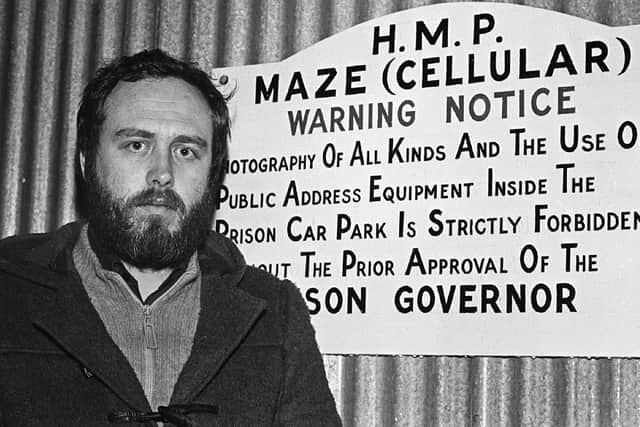

A key moment was the April 1981 and August 1981 ‘Hunger Strike’ by-elections, when Bobby Sands and then Owen Carron won Fermanagh-South Tyrone as the Anti-H-Block Armagh Political Prisoner and Anti-H-Block Proxy Political Prisoner candidates. Both did well and defeated high-profile unionist candidates, but at that point it couldn’t be assumed that it amounted to a victory for Sinn Fein: all sorts of other factors, not least the SDLP not contesting, were in play.

The victories did pose a dilemma for Sinn Fein. The party had developed a skilled propaganda machine and built strong roots in a number of areas, yet what was the purpose of those if it wasn’t reaping electoral dividends? But nor was there any likelihood at that point – particularly because of the hatred of Margaret Thatcher in republican areas – of the IRA rowing back from its campaign and allowing Sinn Fein to contest elections on the back of a ‘democracy only’ platform.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe response to the dilemma came in the form of a strategy first outlined by Danny Morrison at Sinn Fein’s ard fheis a few months later: “Who here really believes we can win the war through the ballot box? But will anyone here object if, with a ballot paper in this hand and an Armalite in the other, we take power in Ireland?” In essence it allowed Sinn Fein to test the depth and breadth of electoral support without any prior ceasefire or decommissioning from the IRA; yet holding out the possibility of politics taking priority at a later stage if it looked like the ballot box was delivering the sort of dividends that terrorism never could.

For me personally – and for many, many others (and not just unionists) – it was a morally repugnant strategy. But it seems to have worked. In its first proper electoral outing, in the Assembly election in October 1982, Sinn Fein came in fourth with 10%, nudging just ahead of Alliance on 9%. Not spectacular, perhaps, but it sent a very clear warning to the SDLP (on almost 19% that there was a new and very significant electoral choice for nationalism/republicanism. So significant, in fact, that I’m pretty sure it became one of the fuelling factors which led to the Anglo-Irish Agreement in November 1985.

But from that first election Sinn Fein has grown to become the largest party in the Republic (although we can’t be certain yet if that was just a blip) and just 1,200 votes behind the DUP in the last Assembly election. The journey to where the party is now has required a series of U-turns (let’s be honest, it doesn’t seem all that long ago that it wasn’t willing to take seats anywhere) but each shift has been thought-through and taken with overwhelming support from the ground upwards, albeit with huge propaganda pressure from the top downwards.

In the early 1990s who would have thought that Sinn Fein would be willing, almost eager participants in an Assembly that sat in the old NI Parliament; or that Martin McGuinness would have served as deputy to three DUP leaders in a row? Yet the party did all of that. And did it without any major fallouts or splits.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThat latter point is an important one. Fair enough, the DUP has ended up in an ‘ourselves alone’ deal with Sinn Fein, but that was a journey which required shifting from anti- to pro-agreement; a huge battle with the UUP; a massive fallout with Jim Allister; the brutal dumping of Ian Paisley; the humiliation of Sinn Fein keeping it out of the Assembly for three years; one setback after another from successive UK governments; and a series of battles and trading punches with other elements of unionism.

Maybe the key difference between Sinn Fein and unionism is that it seems capable of making most of its changes in private and then launching them with unanimous support. During the Good Friday Agreement referendum campaign in 1998 I had a long private chat with a key Sinn Fein ‘player’ in a room in the BBC. I asked him if it had been difficult to sell some of the stuff to republican bases: “Yes, very difficult at times. But we can always rely on people from the unionist No campaign to tell us how well Sinn Fein has done and how much Trimble and the British have sold-out to the IRA.”

Now, while I accept that many nationalists were genuinely pleased to see the IRA campaign ended (a campaign they had never supported in the first place), it’s harder to understand why so many of them – who had previously supported SDLP – shifted to Sinn Fein and continue to vote for it. Parties which were political fronts for the UVF and UDA (the Progressive Unionist Party and Ulster Democratic Party, both of whom were involved in the GFA negotiations) have, to all intents and purposes, crashed and burned electorally. Why? Why do unionists/loyalists seem to have so much difficulty voting for paramilitary-linked parties; yet Sinn Fein grew and grew?

It’s an important question to ask, because it strikes me as too easy to say – as some elements of unionism do – that ‘too many nationalists never had a problem voting for the mouthpiece of the IRA when they got the chance’. Why has Sinn Fein proved so popular in Northern Ireland? Why has it grown so much in the Republic? Why (like Mary Lou McDonald) doesn’t it seem to have a particular problem in continuing to endorse and justify the IRA’s campaign?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd the reason I’m asking – and this is the third of three linked columns about Sinn Fein – is that unless unionism fully understands why Sinn Fein does so well it will never be able to deconstruct that success and respond with some new strategies of its own.