Alex Kane: This unionist has little hope for a brighter future

It’s actually a more difficult question to answer than you might think; and that’s because, as I have noted many times, unionism doesn’t come in the same wrapping. Off the top of my head: party political unionism, civic unionism, loyalism, liberal unionism, Orange/non-Orange unionism, small-u/big-U unionism, traditional unionism, for-God-and-Ulster unionism, secular unionism, truculent unionism, accommodating unionism, paramilitary unionism, Brexit unionism/non-Brexit unionism. The list seems endless. What they have in common is a commitment to the constitutional integrity of the United Kingdom, but after that, all bets are off.

I was about 17 when I first gave serious consideration to what unionism meant for my generation. This would have been in the spring of 1972: violence was rampant, Stormont prorogued, the SDLP, Alliance and DUP all new electoral players, unionism fracturing, a secretary of state rather than prime minster, and I already knew people who had been murdered.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI cut out a newspaper piece in November 1971 about a speech by Conservative PM Edward Heath: ‘Many Catholics in Northern Ireland would like to see Northern Ireland unified with the South. That is understandable. It is legitimate that they should seek to further that aim by democratic and constitutional means. If at some future date the majority of the people in Northern Ireland want unification and express that desire in the appropriate constitutional manner, I do not believe any British government would stand in the way. But that is not what the majority want today.’

My reading of Heath’s comments led me to a stark conclusion and steered my thinking for the next couple of decades: if the Union was to survive then unionists had to ensure that support for it continued to grow even during periods when birth rates for Catholics moved ahead of birth rates for Protestants. That meant supporting a strategy of cross-community cooperation underpinned by equality of citizenship. Putting it crudely – and paraphrasing Terence O’Neill’s clumsy ‘treat Catholics like Protestants’ approach in 1968 – if people from a perceived nationalist background didn’t believe they were viewed as second-class citizens then they might take a more sanguine approach to Irish unity.

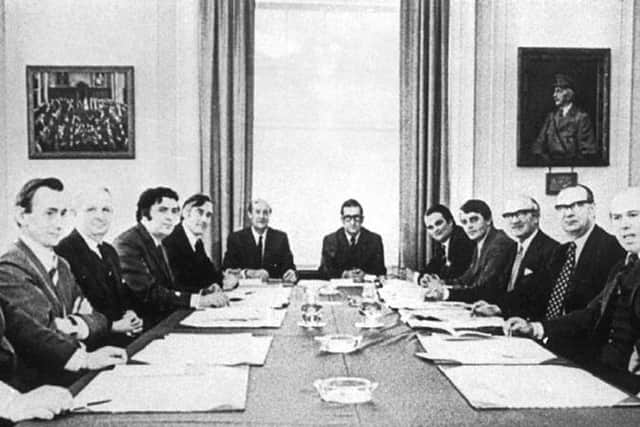

That’s why I supported Brian Faulkner and Sunningdale. It was clear at the time that local nationalism, along with the two governments, pushed him far too hard and too fast on a Council of Ireland and rendered his position within mainstream unionism untenable; yet it was also clear, set-in-stone, any future government would be built on power-sharing. But the collapse of Sunningdale and the mixture of anger and distrust on both sides saw the hardening of positions, with few lessons learned. Seamus Mallon’s ‘Sunningdale for slow learners’ jibe at unionism 25 years later was a great soundbite, but missed the reality that, under John Hume’s leadership, the SDLP more or less ignored bridge-building with any element of unionism.

Anyway, after Sunningdale and with the chances of power-sharing on hold for who knew how long, I shifted attention to integration. Looking back it now looks like a doomed exercise in tilting at windmills, but then it was about creating political vehicles which would be open to anyone in Northern Ireland from any background. That’s why I supported the main UK parties organising and fielding candidates here. But again, it soon became clear that the London end had no interest. And even when the Conservative conference voted in favour of organising in 1989, successive Conservative governments treated the local organisation as a poor, embarrassing, backward cousin.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy the mid-1990s the entire focus of political movement across the UK was shifting to regional devolution, meaning the integration project was dead. The only game in town – as it was in Scotland and Wales – was devolved government with extensive powers. Nationalism and unionism were prepared to play the game: and let’s not forget that the DUP was involved in the first few hands in 1996-97 and simply reshuffled the pack in 2003 and played their own side-game with Sinn Fein thereafter.

In 1998 I supported the Good Friday Agreement. It wasn’t perfect, but it was a moment which hadn’t existed since 1974. On reflection, it was a mistake. We got too caught up in the prospect of peace and didn’t tie up the loose ends. None have been tied up since; indeed, all the agreement did was confirm the scale and nature of the chasm between us. There was going to be no growth of a centre ground, The two so-called extremes became the centre and cut their own ourselves alone arrangement: two governments in the one Executive. A quarter of a century after the peace process began the polls still indicate 80+% of those who vote are voting for us-and-them parties.

That’s where we are. That’s where we will remain. A permanent numbers game: either just hanging onto the Union, or voted into a united Ireland. And the prospect of border poll forever in the background making it impossible for the two main constitutional communities to even consider the concessions required for compromise and accommodation. Worryingly, we spend so much time focusing on the past and commemorating our own triumphs and martyrs, we have become blind to the fact that our present heroes tend to be dead rather than alive.

So what kind of unionist does this make me? The sort of unionist who no longer believes that there can ever be genuine cooperation or a stable NI. The sort of unionist who believes that civil exchange is possible between the communities – but not so civil that the constitutional issue can be set aside, that legacy/narrative differences can be resolved, or that the vast majority of people won’t continue to vote for us-and-them parties. The sort of unionist who thinks that it probably wouldn’t take very much to push us towards violence again. The sort of unionist who hopes that the next generation can do better than mine did.