Belfast Agreement 25 years on: Now we can see that peace rests on shaky foundations, and that Stormont has been a disaster

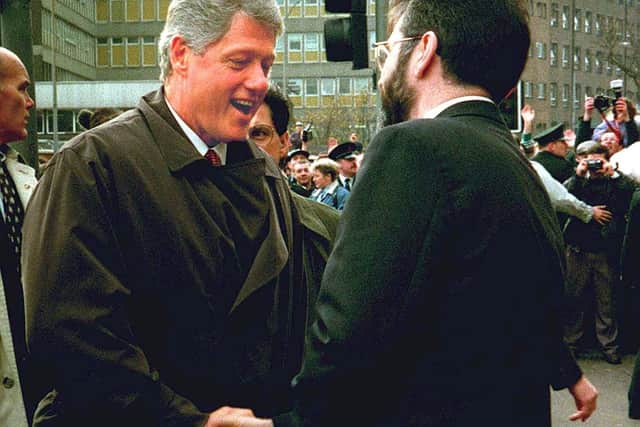

President Biden, long known as a keen enthusiast for Irish unity, is expected to join celebrations in Belfast and Dublin. It seems likely that Tony Blair and Bill Clinton, two of the surviving midwives of the 1998 deal, will emerge to absorb renewed applause.

Since all are practised exponents of the principle that whatever is expedient is justifiable, there are some topics they may prefer to avoid, such as Biden’s backing for the chaotic US retreat from Afghanistan. In contrast, the Belfast Agreement is widely regarded as a safely unquestionable policy success.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDoes it deserve that reputation? It is true that since April 1998, when it was signed, bombing in Northern Ireland and the mainland has mostly stopped. Attacks on the security forces have greatly diminished. Cross community killings have largely ended, and civil and social activity have all but recovered.

And yet we are now increasingly aware not only that this peace rests on shaky foundations, but that it’s threatened by continuing movement in the constitutional bricks. There are many more “peace walls” which separate communities today in Belfast than existed in April 1998.

The performance of the Northern Ireland Assembly has been a disaster. Its enforced categorisation of “nationalist” or “unionist” has merely institutionalised sectarian difference, with its members reflecting the antipathies of those who elected them. Since 1998 it has been in suspension for 40% of its existence, leaving Northern Ireland without a government for long stretches of time.

Both republican and loyalist prisoners were released under the terms of the Agreement, supposedly into a newly peaceful Northern Ireland, but the curse of paramilitarism has not vanished. The loyalist paramilitaries are still armed and involved in criminal activity. “Dissident” republicans are also active, and issuing threats to security forces: it is thought the “New IRA” was behind a recent attempt to murder an off-duty policeman coaching his son’s football team.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs the political centre ground of the UUP and SDLP has shrunk, the electorate has rewarded those who espoused violence in the past: Sinn Fein, linked to the Provisional IRA - the organisation responsible for the single highest death toll of the Troubles - is now the largest political party both north and south of the Irish border.

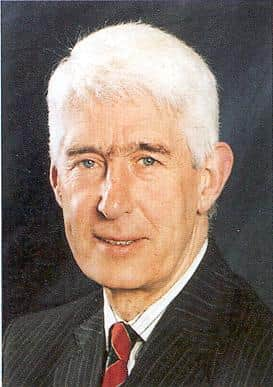

I write as a long-standing critic of the Belfast Agreement, which I opposed in 1998. That wasn’t because - then or now – I didn’t wish for peace. It was because I believed that the sectarian structures and underlying principles written into the Agreement would pose a serious danger in the long term, not only to Northern Ireland’s place in the UK, which as a unionist I supported, but also to the democratic fabric of Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland itself

That belief now appears to be confirmed by the current trajectory of events, particularly the recent vulnerability of the Republic of Ireland to the electoral advances of Sinn Fein. It’s a trajectory that fills me with dread, not satisfaction. But it is worth revisiting the reasons why, in the role of a political Cassandra, I predicted this danger as far back as 1985: (Liberty and Authority in Ireland by RL McCartney QC MPA - Field Day Pamphlet Number 9 1985).

The foundation of the Republic of Ireland was the Irish Free State, the product of the 1921 treaty talks between the British government and Irish negotiators led by Michel Collins and Arthur Griffith. The vicious civil war over the Treaty gave rise to two main political parties, Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil, representing those who had backed the Treaty and those who opposed it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe latter party was led by Éamon de Valera, who later became Premier of the State and architect of the 1937 Constitution, which conferred extensive powers on the Catholic Church over education and social issues. These parties were both conservative and relied heavily on the Church to consolidate their support. In comparison to other European democracies there was - and still is - an unusually narrow range of political and ideological difference between them.

Then came Sinn Fein. When the Sinn Fein spokesman Danny Morrison declared in 1981, “will anyone here object if, with a ballot paper in this hand and an Armalite in the other, we take power in Ireland?” he was stating a dual strategy which his party held up until 1998. Not only did his statement confirm that Sinn Fein and the IRA have been, and are, inextricably linked, but it also challenged the constitutional nationalist parties to object to Sinn Fein’s legitimacy.

After all, it shared with them a mutual objective in Irish unity, and the imperative to seek it which was enshrined in the Republic’s constitution. They were thus compelled to agree with its aims, if not its means. This was the Trojan horse which would allow Sinn Fein to attack liberal democracy in the Republic of Ireland and to dominate in Irish America, where its increasingly energetic self-promotion is funded by US donations.

Although the long-term objective of Sinn Fein was to “take power in Ireland” its initial field of operations was almost exclusively in Northern Ireland. It was only in Northern Ireland that the attainment of Irish unity could actually be attempted, by working to win the support of the nationalist population away from the SDLP and to weaken the position of the unionist one. Sinn Fein’s contempt for successive governments of the Republic and for the Church was veiled by the necessity for some temporary accommodation because of their shared objective of Irish unity.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe fragility of the political establishment in the Republic has now provided the chance for Sinn Fein to exploit the ballot box there too. The insistence of Irish conservative nationalism on a unanimity of political outlook - reflecting Catholic social teaching and a shared goal of geographical unity - caused a stagnation of the conflict between economic and social ideas and values which provides any democracy with a true political dynamic.

Two conservative and broadly similar parties offered the electorate little meaningful choice, particularly those at the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum. The missing dynamic was replaced by the pursuit of a vision of Irish unity which became more mythic than realistic. Few politicians in the Republic of Ireland have dared openly to evaluate the likely outcomes of Irish unity in political, social, and economic terms, including the implications of a million unionists suddenly entering the state. Instead, the nationalist aspiration settled into a form of verbal republicanism combined with a comfortable acceptance of the status quo.

In 1985 I warned that the unaddressed economic, social, and political problems of the Republic would eventually provide the material which an unchecked Sinn Fein would detonate; since while it fed off shared nationalist aspirations it simultaneously offered a theoretical programme of social reform which filled the void left in the Republic by the absence of any real left-right choice.

Nor did Sinn Fein hesitate to oppose the Church by supporting divorce and contraception. Furthermore, Sinn Fein was confident that its devotion to the nation in its fight for Irish unity ensured that it would ultimately be forgiven for any IRA violence.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the decades since Morrison’s declaration of how Sinn Fein would take power in Ireland, Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil increased their political efforts in support of Irish unity, to keep pace with Sinn Fein’s increasing success. At the same time, successive British governments revived their policy of disengagement from Northern Ireland because of the ongoing political and social unrest there, and the effect of the IRA's mainland bombing campaign. The effect has been to isolate Unionists while fuelling an increasingly buoyant republicanism.

The middle ground which was once occupied by the Ulster Unionist and SDLP parties has been largely destroyed. Sinn Fein has become the largest single party in Northern Ireland and is entitled both to appoint the First Minister and have first choice of other ministerial posts. In the Republic it is also the largest party, forcing Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil into a musical chairs coalition to keep it out of office. But for how long?

The collapse of support for the Catholic Church in the Republic in the wake of the child abuse scandals has severely reduced its power to influence the electorate. Sinn Fein, meanwhile, is promising a “progressive” left-wing programme of social reform and justice, which appeals to a discontented younger generation with little understanding of the party’s history but who find it cool to sing jingles lauding the IRA at sporting and entertainment events.

I believe that some Irish politicians, such as Micheál Martin, have already woken up to the profundity of the existential threat which Sinn Fein poses to democracy in the Republic of Ireland. Yet even as stories are breaking in the Irish media about Sinn Fein’s links to the Dublin crime world, and its efforts to silence journalists by means of aggressive “lawfare”, the party’s momentum may prove unstoppable.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhat now seems certain is that the current direction of the “peace process” holds greater dangers for both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland than it does for mainland Britain. Over a number of decades, the British government has made clear its long-term policy of disengagement from Northern Ireland, not least by the 1993 Downing Street Declaration’s avowal that Britain has “no selfish strategic or economic interest in Northern Ireland”.

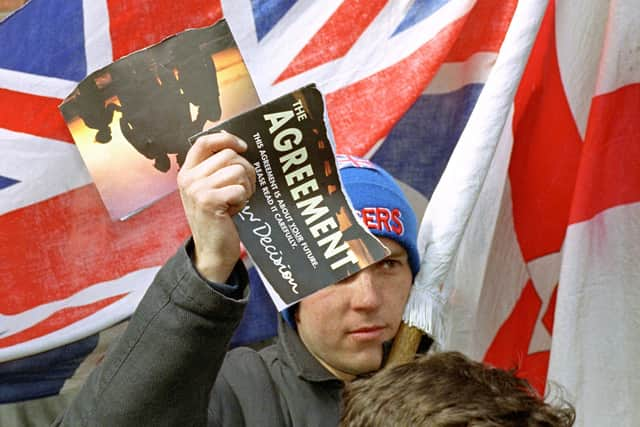

In the 1998 run-up to the Agreement, Prime Minister Tony Blair made ten pledges to voters, many of which subsequently proved disposable: the very first was that “there will be no change to the status of Northern Ireland without the express consent of the people of Northern Ireland.” Today the status of Northern Ireland has been changed radically, and without any “express consent”.

Post-Brexit, it finds itself subject to EU rules which cover the Republic of Ireland but from which the rest of the UK is exempt. It is also separated from the rest of the UK by an Irish sea customs border, to which its Prime Minister Boris Johnson agreed – having previously promised them such a thing would only happen “over my dead body”.

The dilemma for the British Government has long been that any precipitate withdrawal could provoke a violent Unionist reaction, while the Republic of Ireland would be left to cope with the destabilising effect on its own economy and security. The solution for both governments would therefore have to be a drawn-out one.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe medium for their attainment was to obtain an IRA ceasefire by offering a gradual but inevitable transition to a United Ireland, through a power-sharing assembly in which Sinn Fein would play a major role. There is little doubt that John Major initiated indirect contacts with the IRA with the single purpose of eliciting Sinn Fein/IRA's price for a suspension of violence.

April 10, 2023 marks the 25th anniversary of the Belfast Agreement, also known as the Good Friday Agreement.

The negotiated price was a “process” for a gradual transition of Northern Ireland into the Republic. Gerry Adams made it clear in a 1995 speech to the Sinn Fein party faithful that continuing political momentum towards a united Ireland was necessary to his definition of any “peace process”: “We demand that the British government commence the process of disengagement from our country. A peace process has been built. 1994 was a year of change. 1995 must consolidate the peace and make change irreversible."

The direction of British policy was first presented in principle in the “Downing Street Declaration” of 1993 and in working detail in the “Framework Documents” of 1996. The Belfast Agreement was the final piece in the plan. The result of British government strategy has been to make the pro-Union citizens of Northern Ireland feel ever more isolated and deceived, as they watch their rights as UK citizens being progressively diluted.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the same time they have witnessed the ascent to power of Sinn Fein, a republican party which still actively celebrates those who carried out a sectarian 30-year campaign of IRA violence. That combination, which shows every sign of intensifying, represents the worst possible background for any border referendum.

Although a border referendum may be long postponed, when it is finally held Sinn Fein will in all probability be in power in Ireland, north and south. In the event of a narrow vote for a united Ireland, it is equally likely that a significant proportion of the people of Northern Ireland would reject the result, with, I fear, a minority of loyalists potentially willing to use force in opposition.

That vision of civil unrest would not only signify dark days for Northern Ireland, but for the Republic of Ireland as well. The “peace process” has now been “processing” politically for twenty-five years, while failing to dismantle sectarianism and paramilitarism. It seems more likely to result in disaster for Ireland rather than unity.

So too would the ascent to the Irish government of Sinn Fein, a party that once lobbied for the early release of the IRA killers of Detective Garda Jerry McCabe. In opposition, Sinn Fein is already demonstrating illiberal, intimidating behaviour which should act as a warning to potential voters: that will only intensify in office, where the party will not hesitate to demonstrate the authoritarian instincts which have defined it for so long.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNor, having gained power, will it cede control easily. London and Dublin may then come to regret the existence of a political monster which they, and this drawn-out process, have helped to create.

SF/IRA's policy of taking power in Ireland on the back of violence and the ballot box has a dark history. Friedrich Engels, a revolutionary associate of Karl Marx, believed that "the parties of order, as they call themselves, are perishing under the legal conditions created by themselves".

Power thus achieved is seldom, if ever, surrendered to democrats. Instead, it is simply transmuted into a permanent fraudulent democracy, in which its liberal facade will be abandoned and its true suppressive character revealed. The real question is whether this is a process to peace or one to perdition?

• This is the first in a daily series of essays on the agreement. On Monday we will run a pro agreement essay by Prof Brian Walker.

• Robert McCartney KC is a former Ulster Unionist and UK Unionist MLA and MP