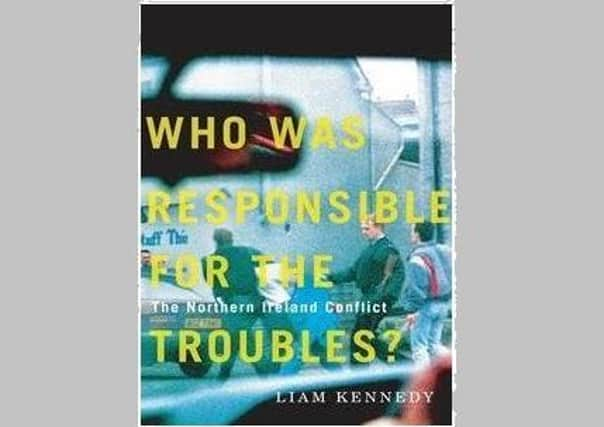

I’m a republican but I think Liam Kennedy’s book blaming IRA for Troubles is a key addition to the debate about Northern Ireland’s past

More specifically, the ultra-nationalists who founded the Provisional IRA and were determined to achieve a united Ireland by armed means regardless of the human cost.

Professor Liam Kennedy does not discount the roles of other actors in the conflict, but Kennedy assembles a formidable array of evidence to support his case.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEven those who disagree with his conclusions will have to acknowledge that his analysis requires a considered response.

Northern Ireland was reformable, according to Kennedy and, by 1969, the Civil Rights movement had secured most of its objectives from the British government in the form of commitments to major reforms, including the electoral laws, fair employment practices and the end of discrimination in the allocation of public housing.

These even extended to abolition of the Special Powers Act and disarming the RUC once widespread disorder ended. Of course, disorder did not end. Rather, the continued deployment of British troops on the streets provided a target of opportunity that the founders of PIRA were determined not to forego, however unprepared they were to wage war effectively.

If they had known where their campaign would lead, they might have thought twice. So might other paramilitary groups such as the UDA and UVF, with their more limited objective of preserving the Union.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne thing Kennedy demonstrates clearly is that far from protecting their communities all of these organisations would inflict far more violence on those they were protecting than any external enemy.

Soon victims included members of kindred republican and loyalist organisations, eventually leading to internal purges of their own members with penalties ranging from punishment beatings to executions.

I have to declare an interest here as a reviewer.

I joined the republican movement as a teenager in the 1960s. When it split in 1969/70, I stayed with what became known as the Officials through their various permutations into the early 1990s, although I ceased to be heavily involved from the mid-1980s.

Like most members of that movement who did not live in Northern Ireland I was relatively ignorant of the complexities of life here before I arrived in Belfast on the eve of internment. I soon learnt how much fear fuelled the conflict.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt swept through nationalist areas where people feared internment would leave them defenceless in the face of loyalist pogroms and, later that same week, I was handed handbills in East Belfast urging men to form companies to protect their communities from the planned Fenian insurrection. I was witnessing the birth of the UDA.

On one occasion I owed my own salvation to a British Army checkpoint on the Newtownards Road. It made me reflect that our strategy for uniting Catholic and Protestant workers against our common enemy, British imperialism, was more problematic than anticipated.

Whenever I was lost again, I kept walking until I reached an Army checkpoint before asking for directions. Soldiers were less likely to shoot you out of hand because they had to file a report afterwards. These reports would come back to haunt them with a vengeance.

Kennedy lets the Official IRA off the hook relatively lightly and makes the point that if other paramilitaries had followed its example of calling a ceasefire in May 1972 thousands of lives, and over 20 more years of communal conflict might have been averted.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOf course, the Official movement paid the price of its stance against sectarian conflict by becoming increasingly marginalised, as did the NI Labour Party.

I believed then, and still believe, that most of those who joined paramilitary organisations did so for honest and honourable reasons, inspired by loyalty to a community or a cause and reinforced by romantic, bowdlerised versions of history, as well as family or peer pressure in many instances.

This is not to deny that the conflict also allowed some criminals and psychopaths to flourish.

There was a tragic inevitability about the process by which working class communities were ‘paramilitarised’. Any organisation seeking to establish a counter state must stamp its authority on the host population. Some people give their allegiance freely, but those who don’t must be made to do so, out of fear if necessary.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNo group would prove more reluctant to bend the knee than youngsters engaged in petty crime, hooliganism and joyriding, some of them from homes rendered dysfunctional by the Troubles. Paradoxically, beatings and shootings of young offenders increased dramatically in the aftermath of Belfast Good Friday Agreement, part of the legacy of conflict.

At a time when major revelations were emerging south of the border of the extent of past institutional child abuse, there were far more brutal systems of punishment being practised on its Northern side. Anyone seen as deviant, or potentially so, was at risk.

Another difference was the failure of voluntary organisations in Northern Ireland, whose job it was to champion human rights, to do so. As Kennedy says, ‘The much vaunted Voluntary Sector was the dog that didn’t bark’.

It was easier, and safer, to pursue human rights abuses by state actors.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough he has little time for the argument that perpetrators of violence were also victims, Kennedy does ‘believe in the possibilities of redemptive change’ and cites examples of former paramilitaries from nationalist and loyalist backgrounds seeking redemption, mainly through their religious beliefs.

Some of us, including former combatants, are more optimistic. We believe that if there was an alternative to the courts that allowed former combatants and victims and survivors to engage in a Truth Recovery Process then some degree of reconciliation, if only on the facts of what happened, would be a meaningful first step towards addressing past injuries and deaths.

As it is, we have a tortuously slow, and expensive, adversarial process in the courts, which exacts a maximum sentence of two years from perpetrators and often leaves families retraumatised and legacy wars revitalised. The latest proposal from one of the leading voluntary sector guardians of human rights that failed to bark in the past, the Committee for the Administration of Justice, is now advocating the abolition of all prison time if the accused pleads guilty and gives what information they can to the DPS.

If that represents a vindication of human rights and the road to reconciliation, we are all in a poor place.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis book it is an important addition to the debate, not alone on Northern Ireland’s past but its future

• Who was Responsible for the Troubles? The Northern Ireland conflict, by Liam Kennedy, is published by McGill-Queen’s University Press. Padraig Yeates is a historian who was involved in drafting the Truth Recovery Process www.truthrecoveryprocess.ie

——— ———

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

With the coronavirus lockdown having a major impact on many of our advertisers — and consequently the revenue we receive — we are more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSubscribe to newsletter.co.uk and enjoy unlimited access to the best Northern Ireland and UK news and information online and on our app. With a digital subscription, you can read more than 5 articles, see fewer ads, enjoy faster load times, and get access to exclusive newsletters and content. Visit https://www.newsletter.co.uk/subscriptions now to sign up.

Our journalism costs money and we rely on advertising, print and digital revenues to help to support them. By supporting us, we are able to support you in providing trusted, fact-checked content for this website.

Alistair Bushe

Editor