Lord Bew: Supreme Court is right to say Northern Ireland's constitutional status is unchanged by protocol but even so government must address unionist alienation

Strictly speaking, the Supreme Court is quite right. But the ruling’s rather brief assertion on this point is unlikely to reassure some unionists.

Some will brutally say that this is simply a function of the suspicious, paranoid, self-defeating nature of modern unionism. But that would be neither fair nor right.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe problem, in part, lies in a legal style of presentation and explanation which does not give enough explanatory weight to historical context even when dealing with matters clearly saturated with historical and political realities.

Instead, the Supreme Court ruling, as is understandably typical, simply bumps along from acts of parliament to other legal decisions in a rather self-enclosed way.

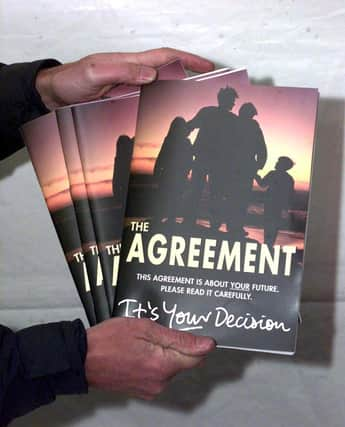

But let us be clear — the protocol does not constitute a change to the constitutional status of Northern Ireland. Why? Because the constitutional status of Northern Ireland depends historically on the Government of Ireland Act 1920 which opened the way to two Parliaments in Ireland and the consent clause of the Belfast Agreement of 1998, as placed in UK legislation.

Of course, this is not an end to the discussion of unionist rights in the current controversy. The United Kingdom’s government, as the sovereign government, is given a special responsibility under the agreement to allay the long-term alienation of either political community in Northern Ireland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere is no question that the UK government has a responsibility to address the current alienation in the unionist community generated by the protocol. In fact, this is what the UK government is attempting to do in its ongoing negotiation with the EU.

The Act of Union of 1800 is of great importance because it sets the context of the Government of Ireland Act of 1920. It explains why the Northern Ireland readers of the News Letter are reading it in constituencies that have been represented in the UK Parliament for over 200 years. The Union is above all a political conception — to create one Parliament for both islands — though it does contain important economic elements, notably article VI.

The political conception is ambitious: Edmund Burke, the brilliant intuitive political thinker, had argued in the troubled and violent 1790s that it was necessary to create a context in which a good Englishman and a good Irishman would speak and think in the same way.

There would be one united emotional imagined community. In 1800, Prime Minister William Pitt and the great Ulsterman Lord Castlereagh fully agreed and put this idea at the heart of their advocacy of the Union. The idea was to create one effective political nation across two islands.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBluntly, this idea failed in the nineteenth century. Delay in implementing Catholic emancipation and, above all, the Famine, played their part. In 1921, 26 Irish counties left the Union — which obviously constitutes a very substantial dilution of the original act.

A new guiding concept replaced it and essentially still prevails. By 1920, as the then Prime Minister Lloyd George explicitly said, there were in effect two nations on the one island of Ireland: hence the need for two Parliaments. And indeed, new language on trade, reserving that matter to the UK Parliament.

The democratic basis for this new arrangement was firmed up, through the granting of nationalist consent, in the Belfast Agreement. This Agreement has important North-South and East-West dimensions reflecting the two local identities. These are the real underlying realities — legislative and political — which underpin Northern Ireland’s place in the Union, not article VI of the Act of Union 1800.

The court explicitly addresses the status of article VI, which it now states to be modified by the protocol. This article is part of Pitt’s historically failed but imaginative conception. He argued that Anglo-Irish relations prior to the Union had been characterised by “illiberality” and “neglect” of Irish economic interests by England.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis was a view, incidentally, strongly supported by Northern Irish Presbyterian business interests in Belfast. Article VI was designed to stop this unfairness, but it is, alas, long since part of a tragic failure of the original Union project. Trade relations for Northern Ireland since 1920 have been dealt with in an entirely different way.

The court rejects the appellants’ wider interpretation of article VI but only briefly and laconically hints at the wider political and historical context which really requires to be fully stated.

The court’s ruling is intended to stabilise, but the rather ex-cathedra and decontextualised nature of its propositions rather deprive it of its due weight.

Revealingly, when the court veers into historical chronology, it does not do so in a convincing way. In its attempt to offer a timeline genesis of the current protocol crisis, why mention the ill-fated DUP’s ‘supply and consent’ deal with the May government and not mention the December 2017 EU-UK Joint Report which is far more long lived in terms of its real effects.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut the court does point out that the protocol is not immutable and is subject to change.

In its current negotiation with the EU, the UK government could do worse than draw on the principles of fairness and concern for the economic progress in this place which so motivated William Pitt and Lord Castlereagh in 1800. It has made a good start in insisting that the functioning of the protocol must be compatible with the Belfast Agreement in all its aspects.

• Paul Bew is Emeritus Professor of Politics at Queens University Belfast and a Crossbench peer in the House of Lords

• Ben Habib and protocol challengers: The Supreme Court ruling has confirmed our worst fears about the Irish Sea border