Oft forgotten local link with a tragedy on the football field

Thomson was Celtic’s star goalkeeper and a member of Scotland’s national team.

On September 5, 1931, in a game against arch-rivals Glasgow Rangers, he and a Rangers player went for a low ball together.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThomson’s head came in collision with the Rangers’ player’s knee.

Thomson collapsed and died soon after.

He was 22 years old.

And thus a legend was born.

To this day fans sing ‘The Johnny Thomson Song’ about that fateful day. And his grave is a place of pilgrimage.

But, says regular Roamer-contributor Mitchell Smyth, there is another part of the story, often forgotten.

The Rangers player who collided with Thomson as the keeper went for the ball was an Ulsterman.

His name was Sam English and he came from near Coleraine.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“He is the second victim of the tragedy,” writes Ballycastle-born journalist Smyth, now retired after a career with the Toronto Star.

Although he was cleared of all blame, even by Thomson’s family, Sam English suffered cruelly from Celtic fans, who taunted him with calls of ‘killer’ and ‘murderer.’

The cruelty took its toll and he died a broken man.

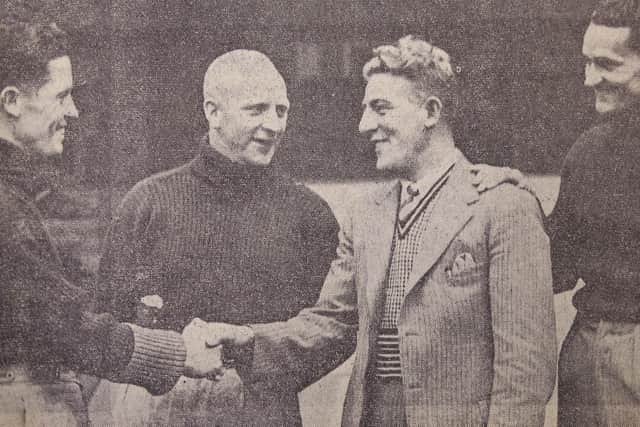

Smyth, who as a reporter with the Northern Constitution in Coleraine wrote English’s obituary in 1967, now shares the story.

Sam English was born in 1908 in Aghadowey, near Coleraine.

In his teens he went to work in the John Brown shipyard on the Clyde, and played football for a minor league team.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere he was spotted by Rangers’ scouts and he joined the team as centre-forward (striker) in 1931.

The tragedy at that September ‘Old Firm’ game, on home turf at Ibrox Stadium, didn’t have an immediate effect on his career.

He went on to score 44 goals (top scorer in the league) in 35 appearances that first season.

In the cup final, against Kilmarnock, he scored the second goal in Rangers’ 3 - 0 win.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut the taunts didn’t let up. And Rangers, reportedly embarrassed by being constantly reminded of the tragedy, transferred him to Liverpool in 1932 for a paltry £8,000.

It was widely viewed as a betrayal by Rangers of one of their own.

And Celtic fans couldn’t forget that as Thomson was being carried off the field that fateful day, some Rangers fans cheered.

Sam English scored 31 goals for Liverpool that season, but then the goals began to dry up, even as there were constant reminders in the papers and from the stands of the part he had played in the death of Johnny Thomson.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe returned to Scotland in 1935, to play for Queen of the South, but it was increasingly obvious that the best centre-forward of his day was now past his prime.

He gave up football the following year, at the age of 28, and went back to work in the Clyde shipyards.

He was quoted at that time as saying that the period after the Ibrox tragedy was “seven years of joyless sport.”

Not much is known about Sam English after that.

He died in a Dumbartonshire hospital in 1967. Reports at the time said he looked gaunt and much older than his 58 years, speculating that this was the result of the cruelties he had endured. (Others said this was the result of the motor-neurone disease which killed him.)

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis name lives on in Scottish football in The Sam English Bowl, awarded annually since 2009, to Rangers’ top scorer. He was inaugurated into the Rangers’ Hall of Fame in 2009, a move that was widely seen as atonement for Rangers’ betrayal of their star striker 77 years earlier.

And here is the ultimate irony: Sam English wasn’t supposed to be on the pitch that September day.

He had hurt his ankle three days previously, and Jimmy Smith was pencilled in at centre-forward for the Old Firm game.

But Smith came to Ibrox that day with a heavy cold, so English was pressed into service. He insisted that his ankle was fine.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe first half was goal-less, with most of the action midfield, so the goalkeepers had little to do.

In the second half, English chased a loose ball; Thomson dived at his feet as English was about to shoot.

Head hit knee.

Thomson did not get up. He died in hospital four hours later. (The game ended 0-0).

The crowd that day was hushed but, a newspaper at the time reported, “a single piercing scream from a horrified young woman” could be heard.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe woman was Johnny Thomson’s fiancée Margaret Finlay, aged 19.

Johnny Thomson’s gravestone, in Bowell, Fife, is to this day a place of pilgrimage for Celtic fans.

It bears the words “They never die who live in the hearts they leave behind.”

It wasn’t long after the tragedy that The Johnny Thomson song was being sung in the pubs of Glasgow:

“I took a trip to Parkhead

To the dear old Paradise,

And as the players came out

Sure a tear fell from my eyes.

For a famous face was missing

In the green and white brigade.

And they told me Johnny Thomson

His last game he had played.”

There are another six verses, to the tune of Noreen Bawn.

Parkhead, which Celtic fans pronounce ‘Parkheed’, and Paradise, are the Glaswegians’ alternative names for Celtic Park.