ROAMER COLUMN: Gaol immortalised by Oscar Wilde’s poem almost sold

and live on Freeview channel 276

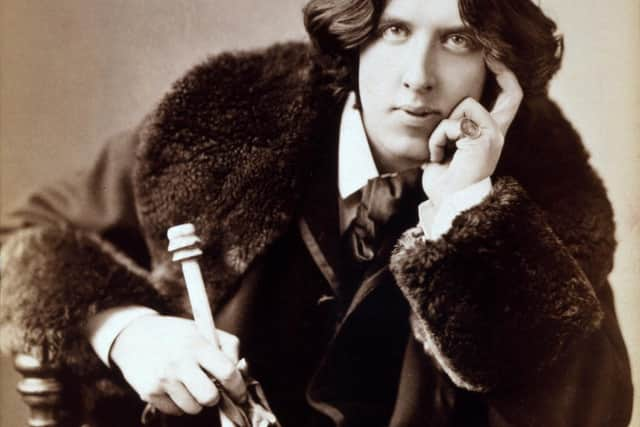

This is where Irish writer Oscar Wilde was imprisoned from 1895 to 1897, for consensual homosexual acts.

The campaign group ‘Save Reading Gaol’ and celebrities including street artist Banksy and actors Liam Neeson and Kate Winslet, want the building to be used for the arts and culture.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPrisons Minister Damian Hinds said in the Commons “...barring any unexpected complications, completion is expected later this autumn.”

There are welcome rumours that it’ll be used for ‘charitable purposes’, not investment.

In early September 2016 I walked through the Gaol’s thick-walled, ominously fortified entrance.

Built in 1844 and closed in 2014 it was immortalised in Wilde’s most famous poem, the Ballad of Reading Gaol, a grim indictment of the death penalty and the penal system.

“I never saw a man who looked

With such a wistful eye

Upon that little tent of blue

Which prisoners call the sky.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI’d been introduced to the poem when I was a pupil in Portora Royal School in Enniskillen - which Wilde attended between 1864 and 1871- and I’d always been haunted by that “little tent of blue”, the convict’s universe, framed by an impenetrable, iron-barred window high in his cell.

The gaol that I visited in 2016 hadn’t ever been open to the general public and I’d sped there on the fast train from London to ensure that my signature was first in the visitors’ book.

In contrast, Wilde signed his famous Ballad merely with his prison number - C.3.3 - when he wrote the poem after his release.

And his anonymity echoed in Enniskillen.

On my first morning in Portora’s Assembly Hall in 1960 I sat beneath a wooden memorial panel with Wilde’s brightly-painted name prominent amongst the faded names of other eminent old-boys.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis had been scrubbed out when he was imprisoned for homosexuality, and then restored in fresh, shining, sliver paint in later years.

Keen to see his cell I hurried through a series of heavily padlocked, internal iron gates, climbed the steep, narrow, iron stairs in the gaol’s C-Wing and on the first floor landing, past a dozen identical, red-painted doors, I found the eye-level label for cell C.2.2.

(In Wilde’s day it was cell C.3.3. before an administrative reallocation of cell numbers changed it to C.2.2.)

Inside is a table, an iron bed, a toilet, a sink and the high-level window to “that little tent of blue.”

Wilde was completely alone here for 23 hours a day.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was allowed out only to walk inside a wooden exercise wheel or to attend chapel.

He had to wear a hood over his head when out of his cell, preventing eye contact with other inmates.

Talking to prisoners was strictly forbidden.

Initially he had no books or writing paper.

He spent two years here, imprisoned for “acts of gross indecency with another male person.”

His ‘gilded’ life was over - he was no longer a famous literary figure - just a number.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt broke him from the moment he arrived - the body-search, the mug shots, the body measurements, the uncomfortable prison clothes, the relentless, repetitive, forced labour and the grinding, dehumanising, solitary confinement.

“One of a thousand lifeless numbers, as of a thousand lifeless lives,” he penned in De Profundis (From the Depths), the extended letter from gaol to his lover, Lord Alfred Douglas.

The prison architecture today is more or less the same as it was then and the original door from Wilde’s cell is now on an observation plinth in the Prison Chapel.

Wilde languished behind it for two years while it occasionally clanked open for food, a few approved books and several sheets of writing paper a day. And then clanked shut.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe had to hand over each day’s writing of De Profundis to the prison governor.

Exiting the jail in 2016 I told a tour-guide that I’d been a pupil at Portora and Wilde’s writings had been my life-long inspiration.

“Yes,” said the guide “he speaks to every generation.”

A verse in his famous Ballad begins “The brackish water that we drink, Creeps with a loathsome slime…”

I wonder now if Wilde was contrasting Reading Gaol’s water supply with the then pristine Lough Erne around Portora. Or did he foresee Lough Neagh?!