Uncanny resonances with Covid-19 and 19th century fiction

“During lockdown, like many other people,” his note began, “I’ve being doing catch-up reading.”

He has just finished “a lengthy and prophetic piece of 19th century science fiction, set against a totally-baffling pandemic, a ‘viral plague’ around the end of the 21st century.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWritten in 1826, the book mentions “the north-east corner of Ireland, especially Belfast and the short sea-crossing between Antrim and Ayrshire.”

Many of us will know of its author, the creator of one of fiction’s most famous monsters, but the rest of today’s page is George’s summary of the story and “its uncanny resonances with the present Covid-19 pandemic.”

It begins with a rampaging rabble of starving and disease-ridden ‘North Americans, the relics of that populous continent’ who, fleeing from a deadly ‘plague’, ‘a pestilence’, a ‘pandemic’, caused by the outbreak of a virus which is spread by minute airborne particles, head for ‘lands less afflicted than their own’.

Several hundred braved the Atlantic in a flotilla of unseaworthy little boats, landed in the West of Ireland and ‘took possession of such vacant habitations as they could find, seizing upon the superabundant food, and the stray cattle’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUnsurprisingly ‘this roused the fiery nature of the Irish’ and retaliatory raids ensued.

Many of the Americans managed to escape and headed east, followed by ‘unnatural numbers’ of ‘disordered multitudes of the Irish,’ now beginning ‘to feel the inroads of famine’.

The Americans and Irish then joined forces and travelled to Belfast ‘to ensure a shorter passage’ to Scotland and ‘poured with one consent into England’.

At the same time large numbers of refugees fleeing the ravages of the virus in Europe also poured into England.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

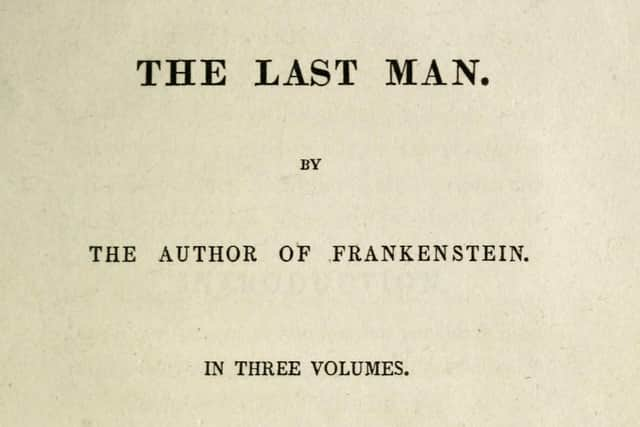

Hide AdEntitled The Last Man, the book was written by English novelist Mary Shelley and was published in 1826.

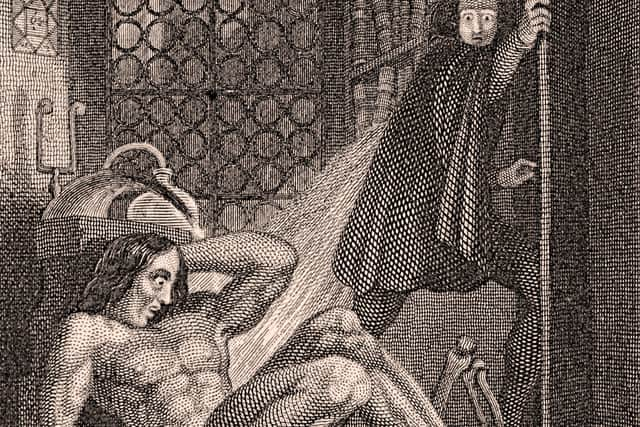

Mary eloped to Italy in 1816 with poet Percy Bysshe Shelley where they married and, in the same year, she published her most famous novel, Frankenstein: or the Modern Prometheus.

Following the deaths of three of their four children in infancy and the tragic drowning of Percy, Mary returned to England in 1823 with her remaining son, to write, only to discover that she was already famous, as the author of Frankenstein. Subsequently she wrote four more novels, some verse and five other books. She died in 1851 at the age of 54.

The Last Man was Mary’s first major work after Frankenstein, but it was never as successful as Frankenstein.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIts publication in February 1826 caused general concern because of its disturbing prophetic nature about a future Earth and the apocalyptic end of mankind.

Set in the future, around the end of the 21st century, the book describes the western world being ravaged by an unknown pandemic that originated in Constantinople (Istanbul) where ‘famine and pestilence are at work’.

In 1960 it was republished and re-presented as a work of science fiction rather than as an ancient prophesy.

While the story of Frankenstein is still well-known, The Last Man has never gained the same acclaim.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

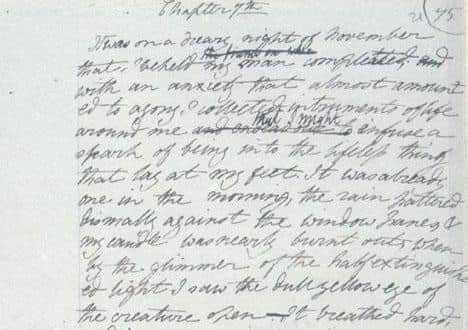

Hide AdWritten in the high-flown language of the 19th century, it is a first-person singular account of an unfolding worldwide catastrophe by narrator and central character ‘Lionel Verney’, who is the orphaned son of an impoverished nobleman.

He would seem to be based on the character of Mary herself. The characters of ‘Adrian’, Earl of Windsor and son of the deposed, last King of England and ‘Lord Raymond’, who becomes Lord Protector of England, which has now become a Republic, are believed to be based respectively on poets Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord George Gordon Byron.

There is much in this dark novel which has uncanny resonance with developments in our time.

For example, ‘Lionel’ recalls that at ‘the commencement of summer we began to feel that the mischief which had taken place in distant countries was greater than we had at first suspected.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd ‘when news arrived in London that the plague was in France and Italy, as a consequence the English, whether travellers or residents…came pouring in one great revulsive stream back to their own country. It was no mighty leap methinks from Calais to Dover. Fools that we were not long ago to have foreseen this!’

However, while words like virus, pandemic, contagious, pestilence occur throughout the novel, not surprisingly there’s no mention of lockdown, self-isolation or furlough, for example.

‘Lionel’ speculates upon what people don’t know about the pandemic rather than on what they do know.

It was known as an ‘epidemic’ but at the time the problem was to find out how the epidemic started and spread.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA contemporary belief was that the disease spread through the air and not through direct contact with people or objects. However, if infection depended upon the air, then the air must be subject to infection.

Whether or not it was spread through the air, what was most disconcerting about this plague was that ‘…it is evil…wide spreading …violent and unmedicable.’

‘Lionel’ asserts that this plague is not what is commonly called ‘contagious’.

Sadly, he and his whole family catch it and die, except ‘Lionel’ who is, at book’s conclusion, ‘The Last Man’.