Letter: I can’t agree with Eoghan Harris's polemics against journalists and the southern media

Your columnist Eoghan Harris writes on the subject of David Trimble and Gerry Adams (David Trimble wasn't 'fascinated' by Gerry Adams - he could barely tolerate his presence, January 6).

As it happens I can agree the heading, but not Mr Harris’ polemics against journalists John Bowman, David McCullough and Dion Fanning (The Currency) and the Southern media generally for their recent analysis of Irish archives. He thinks they help to establish, with the aid of retired Irish officials and the annual release of state papers, “two tropes….the brilliance of the officials in our (Ireland’s) Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) in running rings around the Brits, and the slowness of unionists to grasp what is good for them”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI will not attempt to speak for our journalists other than to say the too few involved work diligently each year at the near-impossible task of entertaining and making overall sense for their viewers and readers of what has become, under the 20 year release rule and catch-up of papers from earlier years, an annual tsunami of Irish and British state papers on Anglo-Irish relations and Northern Ireland. Mr Harris’ perception in his column is different and is worth a response.

As to Mr Harris’ characterisation of “brilliance” in DFA, I shall demur and say we respected the abilities and purposes of our opposites in negotiations, and they respected ours. No one ran rings around anyone. Mr Harris and others can read as much in the lengthy and sober treatise by John Coakley and Jennifer Todd Negotiating a Settlement in Northern Ireland 1969-2019, OUP, 2020, paperback 2023, which includes witness seminars in which a number of retired senior officials, Irish and British, join and speak frankly.

In the 1970s and onwards we were 1) seeking to end the violence which was growing increasingly undiscriminating, vicious and destabilising; and 2) to help achieve this we were trying to make the greatest possible progress in rectifying the decades of gerrymandering and discrimination which nationalists/catholics had endured in a polity in which the majority was permanent and unionist, “a cold house for catholics” as David Trimble termed it in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, 1998 (Mr Harris, as a speech writer for Mr Trimble, may recognise the language).

What happened in the years succeeding the 1970s had much less to do with official personalities in these islands than with the rise of the 24/7 news cycle and media focus on Northern Ireland, the growing influence of Irish America and, most important, another phenomenon, very present in the minds of unionists like David Trimble, the changing demographic in Northern Ireland not only in the composition of the population, but in the composition too of the professions and of business, of society at large. By the 1990s, it could be seen that a majority in Northern Ireland would be no longer permanent and unionist.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

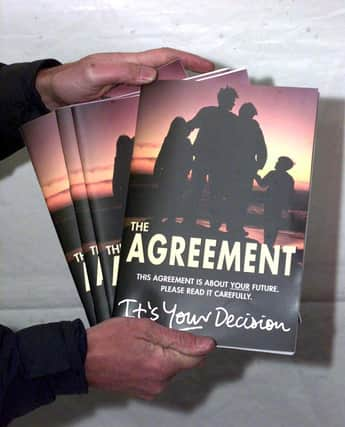

Hide AdThe Good Friday Agreement 1998 was the consequence of decades of negotiations amidst these changes. It provided a fairer deal for nationalists and their aspirations on one side and on the other side a protection of unionist interests and aspirations too. And for both sides, hopefully, a better and far more peaceful future.

What the Agreement could not do was to prescribe the future: this is in the hands of present-day actors and the wider world. David Trimble invoked numerous times in his Nobel speech, the Dublin-born Edmund Burke, whom he adeptly describes as an eminent Irish philosopher, the philosopher of the possible as he puts it, and a brilliant British parliamentarian. Of another Dubliner he says “like one of Beckett’s characters, Iwill go on, because I must go on.” Perhaps he refers to the last line of Beckett’s novel The Unnameable “I can’t go on, I will go on”. Trimble himself says “And we have started. And we will go on.”

Good lines for Sir Jeffrey Donaldson and other present-day political actors?

Dr Declan O’Donovan, Irish official 1972-2014, Joint Secretary, Maryfield, 1990-95